The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was, in 1925, the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). It merged in 1978 with the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks (BRAC), now known as the Transportation Communications International Union.

The leaders of the BSCP—including A. Philip Randolph, its founder and first president, and C. L. Dellums, its vice president and second president—became leaders in the Civil Rights Movement and continued to play a significant role in it after it focused on the eradication of segregation in the Southern United States. BSCP members such as E. D. Nixon were among the leadership of local civil rights movements by virtue of their organizing experience, constant movement between communities and freedom from economic dependence on local authorities.

The campaign to found the union was an extraordinarily long one pitting it against not only the company but also many members of the black community. In the 1920s and 1930s the Pullman Company was one of the largest single employers of blacks and had created an image for itself of enlightened benevolence via financial support for black churches, newspapers and other organizations. It also paid many porters well enough to enjoy the advantages of a middle-income lifestyle and prominence within their own communities.

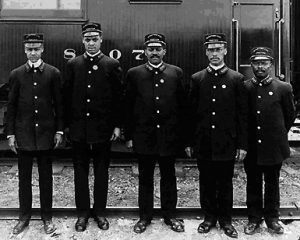

Working for the Pullman Company was, however, less glamorous in practice than it appeared. Porters depended on tips for much of their income and thus on the generosity of white passengers who often referred to all porters as “George”, the first name of George Pullman, the company’s founder (see also Society for the Prevention of Calling Sleeping Car Porters “George”). Porters spent roughly ten percent of their time in unpaid “preparatory” and “terminal” set-up and clean-up duties, paid for their food, lodging, and uniforms, which could consume up to half of their wages, and were charged whenever their passengers stole a towel or a water pitcher. Porters could ride at half fare on their days off — but not on Pullman coaches. They were not promotable to conductor, a job reserved for whites, despite frequently performing some of the conductor duties.

The company had squelched any efforts they made to organize during the first decades of the 20th century by isolating or firing union leaders. Like many other large companies of the time, the company employed spies to keep tabs on their employees; in extreme cases, company agents assaulted union organizers.

When 500 porters met in Harlem on August 25, 1925, they decided to make another effort to organize. During this meeting, they secretly launched their campaign, choosing Randolph, not employed by Pullman and thus beyond retaliation, to lead the effort. The union chose a motto to sum up their resentment over the working conditions: “Fight or Be Slaves”.

At that time the African American community was estranged from organized labor. While the AFL nominally did not exclude black workers, many of its affiliates did. Many black workers saw their employers, whether it was Henry Ford in Detroit or Swift Packing in Chicago, as more sympathetic to them than either their white co-workers or the labor movement. In addition, the economic separation, deprivation, and marginalization of the black community forced by Jim Crow and the doctrine of advancement through self-reliance preached by Booker T. Washington led many black leaders to look with distrust on joining with whites on issues of common concern — and often denied that blacks and whites had any common interests at all. Furthermore, and foremost, white supremacy remained entrenched in most every institution that existed in the US, and these racist beliefs, both subtle and overt, precluded the white labor movement from recognizing the black workers or their organized fronts.

Randolph himself was a prominent member of the Socialist Party. From its inception, the BSCP fought to open doors in the organized labor movement in the US for black workers, even though it faced staunch opposition and blatant racism. As BSCP co-founder and First Vice President Milton Price Webster, put it, “…any time we have an American institution composed of white people there is prejudice in it….In America, if we should stay out of everything that’s prejudiced we wouldn’t be in anything.”

As early as 1900, efforts were put forth by various collectives of Pullman porters to organize the porters into a union, each effort having been crushed by Pullman. In 1925, in the early days of organizing the BSP union, Randolph was invited, by BSCP union organizer Ashley Totten, to address the Porters Athletic Association, in New York City in 1925. Exhibiting a sound understanding of the plight of the black worker and the need for a genuine labor union, Randolph was asked to undertake the job of organizing the porters into a bona fide labor union. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was launched on the night of August 25, 1925.

Key to the success of the union was to galvanize membership by way of a national membership drive, with three of the Pullman company’s largest terminals being most important — Chicago, Oakland, and St. Louis. The man to see in Chicago was Milton Price Webster. He was the son of enslaved parents from Clarksville, Tennessee, who, after successfully purchasing their own freedom, eventually moved to Chicago, where Webster was raised. A former Pullman Porter of twenty years, and a devoted husband (Louie Elizabeth Harris) and father of three, Webster had been fired by the company for attempting to organize porters in the Railroad Men’s Benevolent Association.

Webster was a man of strong convictions. As a Lincoln Republican and a tenured, highly respected captain of Chicago’s Sixth Ward black Republican machine, Webster was a stern, but gregarious leader of men who was well connected throughout the Chicago politic. Not the orator of Randolph’s skill, and not college educated, Webster devoured books and the news of the day, and was a stalwart back room negotiator. He captured his audience with his command of the subject, his keen wit and sharp intellect, and his commitment to alleviating the struggles of the working man.

Although skeptical of Randolph’s socialist affiliations, on the recommendations of fellow union organizer John C. Mills of Chicago, Webster facilitated a series of public meetings for Randolph and Chicago porters, nightly for two weeks. At the initial meeting, after hearing Randolph speak, Webster turned to Mills, agreeing that Randolph was the man to head the organization of the new union. For the next two weeks, nightly meetings were held, with two speakers campaigning for Chicago chapter membership—Milton Webster opening and A. Philip Randolph closing—effectively launching the Chicago division of the Brotherhood.

The Pullman Company’s response was to denounce, with support from the ministers and African American newspapers whom it had cultivated (or bought), the new union as an outside entity motivated by foreign ideologies, while sponsoring its own company union, variously known as the Employee Representation Plan or the Pullman Porters and Maids Protective Association, to represent its loyal employees. Local authorities, such as Boss Crump in Memphis, Tennessee in some cases helped the company by interfering with or banning BSCP meetings.

For the first several years of its existence, the union continued fighting the Pullman Company, its allies in the black community, the white power structure, and rival unions within the AFL that were hostile to its members’ job claims. They also successfully fought efforts by communist to infiltrate the BSCP. The BSCP also tried to involve the federal government in its fight with the Pullman Company: on September 7, 1927 the brotherhood filed a case with the Interstate Commerce Commission, requesting an investigation of Pullman rates, porters’ wages, tipping practices, and other matters related to wages and working conditions; the ICC ruled that it did not have jurisdiction.