Good Morning POU!

Today’s feature is Fred Whitfield.

Born on Aug. 5, 1967, in Houston, Fred Whitfield grew up roping anything and everything in sight. Little did he know at the time that his talent would take him to the pinnacle of ProRodeo success. As of 2003, Whitfield has won seven world titles, including six in tie-down roping and one in the all-around during his storied career; became the third cowboy in history to surpass the $2 million mark in career earnings; and became only the second African-American cowboy in PRCA history to win a world title and the first to win an all-around title. As of 2013, he had surpassed the $4 million mark in career earnings.

Always cool under pressure, Whitfield has made a name for himself in ProRodeo by consistently coming through in clutch situations. His signature “raise the roof” salute caught on with fans across the country who have become accustomed to his dramatic victories. Befitting a cowboy of his stature, Whitfield has won titles at virtually every major rodeo, including four Wrangler NFR aggregate crowns. His 10-head total of 84.0 seconds en route to the aggregate title in 1997 established a Wrangler NFR record and is considered one of the greatest performances in the history of the Wrangler NFR.

The following is from an interview with Fred in June for Vice magazine:

“I’ve won just about everything there is to win,” the veteran roper drawls. “Rodeo’s been great to me, and rodeo don’t owe me a thing.”

He stands at a big 6’2”, never stops moving, and keeps a dip of tobacco tucked in his lip. He’s got two horses hitched to his trailer, and when the colt gets testy with the mare, Whitfield pivots and hisses, “Hey! If you kick her, I’m gonna whoop your ass.” The colt calms right down.

We’re at the 102nd Calgary Stampede—Whitfield’s 24th—and he’s competing in tie-down roping: one of the Stampede’s six rodeo events. He’s turning 47 next month, yet the Texan is beating guys half his age.

“This is the 2005 World Champion buckle,” Whitfield says, pointing at the gorgeous piece of gold metalwork fixed to his custom-tooled ‘FW’ leather belt. “It’s the last one I won, so it’s the one I wear all the time. It’s worth about $18,000 if you had to replace it, and I’ve got eight of them.”

He started with nothing: a poor black kid from a broken home in the heart of white Texas bent on making it in the Lone Star State’s even whiter rodeos. He came and he won. People talked a lot of trash to Whitfield. He got it from both ends: white and black. Whitfield got into fights.

“You see this scar on my face?” he says pointing to the slender slash that runs down his left cheek from the top of his chin. “It happened in 1989. I was in a bar and some guys said, ‘We’re gonna whoop your ass—you better leave,’ and I said, ‘Well, I guess I got an ass-whoopin’ coming because I’m not going anywhere.”

A half-black, half-Indian man was lusting after Whitfield’s girlfriend at an all-black rodeo in Oakland, California. The guy slashed. Whitfield hit back with a lug wrench. And he hit back, again and again. Until the guy couldn’t walk.

“31 stitches,” Whitfield says. “About six inches lower, I wouldn’t be telling you this story—I’d be dead.”

Whitfield isn’t the first African American to make it in professional rodeo—he’ll tell you that—but he has been the sport’s most successful. In his 25-year career, he’s won eight Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) world championships, the PRCA’s coveted All-Around Cowboy award, and $3.2 million USD (a hell of a lot for the sport). He’s won at the Stampede three times, and made $12,500 in Calgary this year.

“I don’t consider myself a famous person,” Whitfield says, “but I consider myself a fortunate person because I’ve had a lot of success in a sport where the percentage of African Americans is less than five percent.”

Early cowboys like cow-biting Bill Pickett, and bull riders Myrtis Dightman and Charlie Sampson paved the way. They were seldom judged for how they really rode, and even in the 1960s, black cowboys like Dightman were being forced to do their events after crowds had packed up and gone home.

Whitfield has experienced his fair share of white trash ignorance too. Racism in rodeo isn’t as bad as it used to be, but it’s far from perfect. Ignorant creeps will still shout “Nigger” at rodeos in some parts of America. He used to fight back—now he walks away. But some parts of rodeo just won’t change.

“It’s still there,” he sighs. “I’d be lying to you if I told you it wasn’t… but nowadays, I think it mostly has to do with jealousy.”

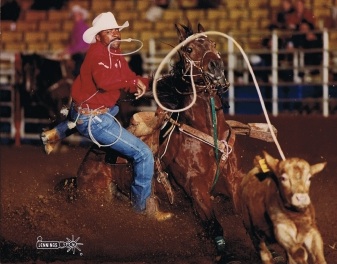

I’ve seen him rope.

A scared little calf runs into the arena, and Whitfield comes after it on a horse, spinning his lasso in one hand with a tie in his teeth. He ropes the calf around the neck, flies off the horse, then flips the calf and binds three of its legs. He does this in 7.4 seconds.

“You know,” I say, with pathetic city-boy feebleness. “Some people find the sport cruel. They’re protesting and stuff.”

“We don’t ever set out to injure an animal,” he tells me matter-of-factly. “But there’s people who fight for what they believe is right, and who am I to say they’re wrong?” Whitfield grins as he says this last part, then lets out a long, dark stream of tobacco spit.

The world’s cruel, I guess. And Whitfield’s written a book about it. Published in 2013, Gold Buckles Don’t Lie: The Untold Tale of Fred Whitfield is as tell-all as they get: a violent alcoholic father who his mother leaves, takes back, shoots in the gut, then takes back again… Little Fred’s consuming rodeo obsession; roping dogs in the Texas sticks, then calves under flickering small town rodeo lights; winning and winning; then women, brawls, and even the rush of rodeo on cocaine. Calgary gets mentioned too: an injured horse, some big money, and a bar fight against redneck American bull riders with Vegas mob ties.

“The first time I read it, I cried my ass off,” Whitfield says of his book. “This is not fabricated shit… It’s gonna keep you on the edge of your seat.”

8-time PRCA world champion Fred Whitfield wins the BP Super Series calf roping at the 2013 Rodeo Houston in Houston, TX.

Whitfield’s married now. He’s got two daughters and he’s mentoring 22-year-old Cory Solomon: another black Texan—and the kid is good, too. But when the younger cowboys take the rodeo night by the horns, Whitfield now (mostly) stays in.

“I don’t need to be standing around where there’s ten thousand screaming women crawling all over you and all that good stuff—I’ve outgrown all that shit.”

I ask him about retirement. He’s one of the oldest guys competing in Calgary and he’s cooled down of late, taking some off for surgery on his neck and shoulder.

“Maybe I’ve lost a step speed-wise, but you can overcome that with knowledge and wisdom,” Whitfield says. “If I show up at a rodeo, I expect to win.”

Even if he’s slowing down, Whitfield’s schedule is still fairly crazy. On July 4, he drove more than eight hours from a rodeo in Montana to Calgary to compete on the same day. He then headed south of the border after competing on July 7 and hit four rodeos in three states—Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah—before coming back to Calgary to compete in the Stampede finals on the 13th. That’s 4,500 km in less than a week. And his whole summer is like this.

“I back in there and there’s 33,000 people screaming when they call my name—and if that don’t get your blood to boiling, then something’s wrong,” Whitfield says. “I don’t want to use the analogy of being on drugs, but once you get this rodeo shit in your system, it’s hard to kick it—man, am I telling you.”