The Gilded Age was one of many ironies for African Americans.

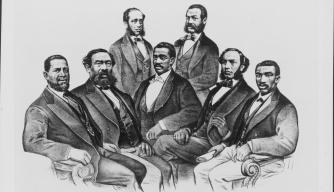

The period between the late 19th century and early 20th century was one of particular hardship for the majority of African Americans. Emancipation had only occurred a few decades earlier and the promises of 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Reconstruction saw gains in politics with quite a few men of color gaining office, only to see Jim Crow strip away any gains made and fierce violence erupt to remind black communities of their second class status.

America’s industrial revolution and the major corporations that it spawned during the Gilded Age (1877–1910) forced an interesting debate on race on an international scale. Effectively, the United States exported two political visions at the end of the nineteenth century that became inextricably linked: white supremacy and American imperialism. Jim Crow, predicated on forcibly imposing and violently upholding white rule over people of color, took shape during the 1890s in the wake of the Mississippi Plan and the enactment of segregation laws in every southern state.

The Mississippi Plan of 1875 was developed as part of the white insurgency during the Reconstruction Era in the Southern United States. It was devised by the Democratic Party in that state to overthrow the Republican Party in Mississippi by means of organized threats of violence and suppression or purchase of the black vote. Democrats wanted to regain political control of the legislature and governor’s office. Their success led to similar plans being adopted by white Democrats in South Carolina and other majority-black states.

However, despite every setback, this was also the period when many Historically Black Colleges were founded.

In 1862, the Federal government’s Morrill Act provided for land grant colleges in each state. Some educational institutions in the North or West were open to blacks before the Civil War. But 17 states, mostly in the South, had segregated systems and generally excluded black students from their land grant colleges. In response, Congress passed the second Morrill Act of 1890, also known as the Agricultural College Act of 1890, requiring states to establish a separate land grant college for blacks if blacks were being excluded from the existing land grant college. Many of the HBCUs were founded by states to satisfy the Second Morrill Act.

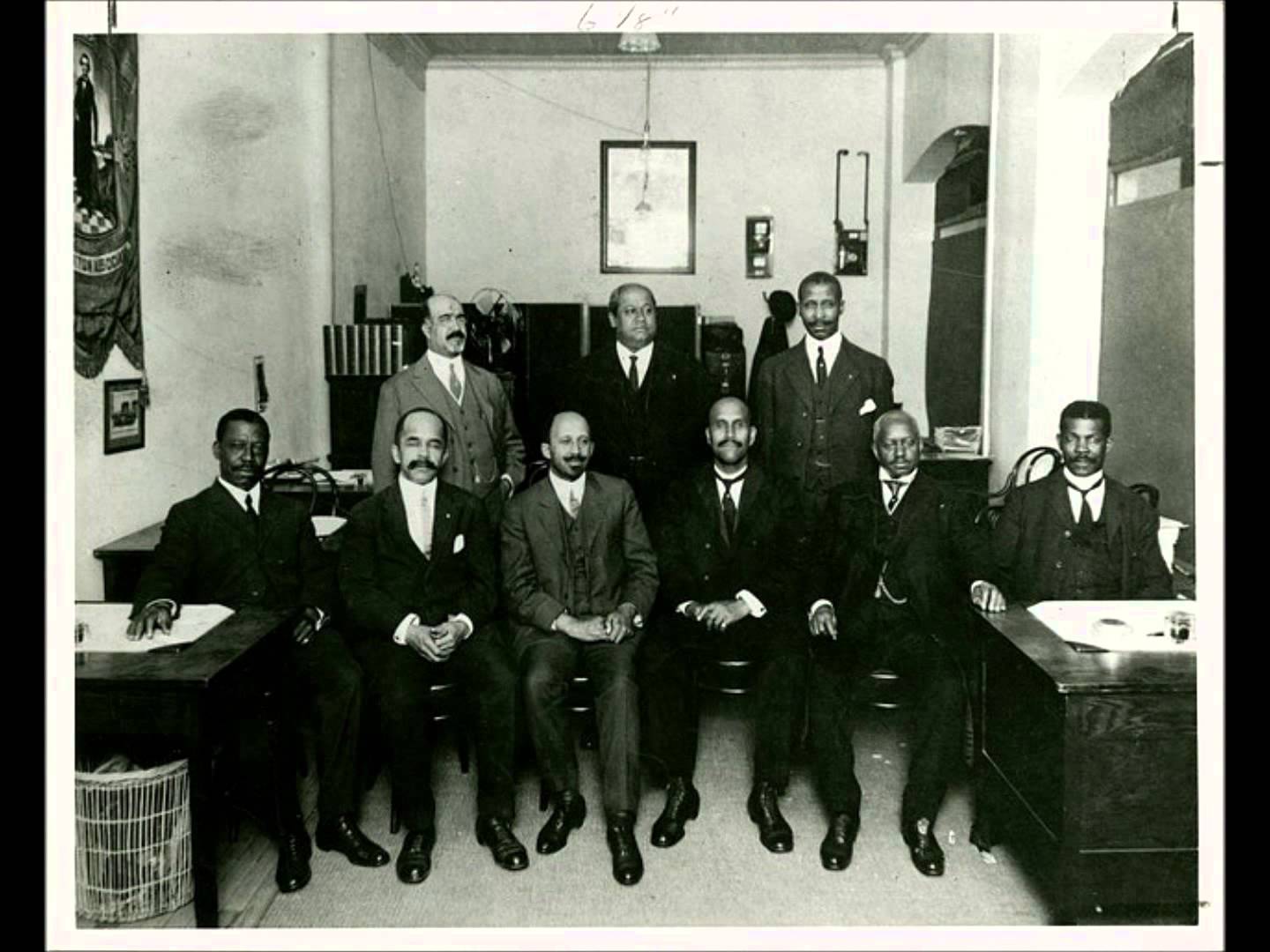

Private HBCUs such as Tuskegee which were founded during the era, were able to grow at rapid paces due to the financial benevolence of some of the wealthiest industrialists of the country.

The school’s original buildings were actually built by its early students. Washington thought labor and knowledge of practical trades were just as valuable and dignified as a typical university education, an idea criticized by activists like W.E.B. Dubois as accommodating to white prejudice and supportive of racial discrimination.

Despite his dependence on white state and private financial support, Washington made sure that Tuskegee had an all-black faculty. It was the first major educational institution in the South to do so, and he made this requirement in a calculated move to “develop Black leadership to the maximum extent.” By the time of Washington’s death, Tuskegee was recognized nationwide and had gained institutional independence.

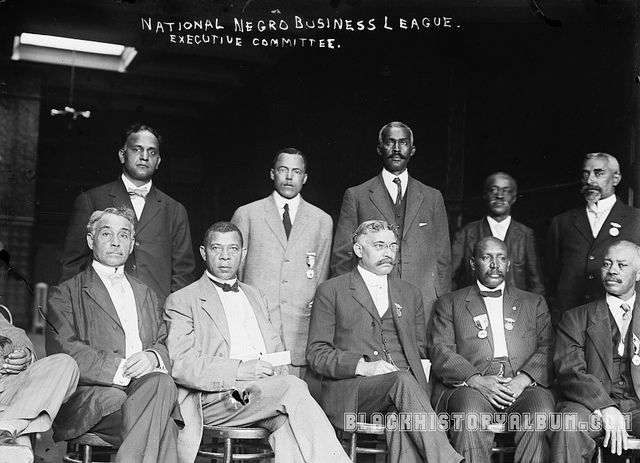

Washington also founded The National Negro Business League (NNBL), an American organization founded in Boston in 1900 to promote the interests of African-American businesses. The mission and main goal of the National Negro Business League was “to promote the commercial and financial development of the Negro.” It was recognized as “composed of negro men and women who have achieved success along business lines”. It grew rapidly with 320 chapters in 1905 and more than 600 chapters in 34 states in 1915.

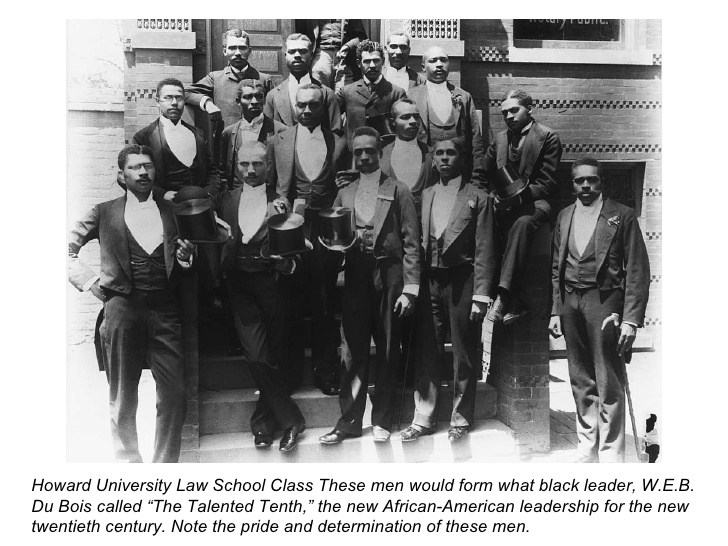

W.E.B. Du Bois and the Talented Tenth

The phrase “talented tenth” originated in 1896 among Northern white liberals, specifically the American Baptist Home Mission Society, a Christian missionary society strongly supported by John D. Rockefeller. They had the goal of establishing black colleges in the South to train black teachers and elites.

Du Bois used the term “the talented tenth” to describe the likelihood of one in ten black men becoming leaders of their race in the world, through methods such as continuing their education, writing books, or becoming directly involved in social change. He strongly believed that blacks needed a classical education to be able to reach their full potential, rather than the industrial education promoted by the Atlanta compromise, endorsed by Booker T. Washington and some white philanthropists. He saw classical education as the basis for what, in the 20th century, would be known as public intellectuals:

Men we shall have only as we make manhood the object of the work of the schools — intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of men to it — this is the curriculum of that Higher Education which must underlie true life. On this foundation we may build bread winning, skill of hand and quickness of brain, with never a fear lest the child and man mistake the means of living for the object of life.

Du Bois writes in his Talented Tenth essay that

“The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst.”

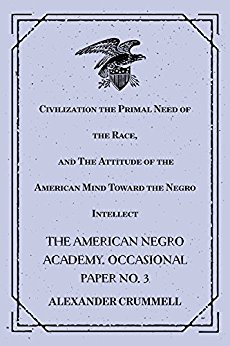

The American Negro Academy was a Scholarly institute that published many works of the Talented Tenth.

The American Negro Academy (ANA) was the first organization in the United States to support African-American academic scholarship. It operated from 1897 to 1928, and encouraged classical academic studies and liberal arts.

It was formed to provide support to classic scholarship, in contrast to Booker T. Washington‘s approach to education. Washington’s Tuskegee University emphasized vocational and industrial training for southern blacks, as he thought this was more practical for the lives most would live in the segregated South, where most blacks lived in rural areas.

The founders of the ANA were primarily authors, scholars, and artists. They included Alexander Crummell, an Episcopal priest and Republican from New York City; John Wesley Cromwell of Washington, DC; Paul Laurence Dunbar, poet and writer in Washington; Walter B. Hayson, and Kelly Miller. Crummell served as the first president.

Their first meeting on March 5, 1897 included eighteen members: Blanche K. Bruce, Levi J. Coppin, William H. Crogman, John Wesley Cromwell, Dr. Alexander Crummell, an Episcopal clergyman, trained in theology and a prominent church founder. DuBois, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, William H. Ferris Francis J. Grimké, PhD a Presbyterian clergymen, trained in theological studies. Benjamin F. Lee, Kelly Miller, PhD professor of Mathematics, known as the first black graduate student to enroll at Johns Hopkins University.William S. Scarborough, John H. Smythe, Theophilus G. Steward, T. McCants Stewart, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, Robert Heberton Terrell, Richard R. Wright.

The Academy was organized in 1897 in Washington, D.C. Black newspapers expressed excitement that the Academy would have wide possibilities to serve a large audience, seeking to elevate the race through educational enlightenment. Through an assessment of statistical tends, mainly concerning black illiteracy, the Academy-based its work that was to then be published in its Occasional Papers. The scholarly contributions aided the spirit of blacks who were being forced into legal segregation in southern states.

An all-male organization, the ANA consisted of those with backgrounds in law, medicine, literature, religion, and community activism. Their collective goal, however, was to “lead and protect their people” and to be a “weapon to secure equality and destroy racism.” American Negro Academy members produced a number of published works discussing and analyzing the African American experience and the issue of racism. They included Disenfranchisement of The Negro, written by J.L. Lowe, Comparative Study of The Negro Problem, by Charles C. Cook, and William Pickens’s The Status of the Free Negro from 1860-1970.