No one can ever say NFL players CAN’T stand on principle and force change within their profession and the larger culture. They most certainly can. They’ve done it before, it remains to be seen if we’ll ever see the brave numbers to initiate change again.

Today we feature the 1965 American Football League players boycott of the All-Star game.

The Stand

The Stand is not about sports, a football game or sporting event, it was one of the most significant events in the Civil Rights Movement in America during the 1960’s. It’s about Segregation, standing against Racism, being a voice for the unheard; it is all about overcoming adversity…the Human Condition.

On January 11, 1965, an unprecedented boycott by African American and white American Football League players ended in victory after AFL commissioner Joe Foss agreed to move the site of the 1965 All Star game from New Orleans to Houston.

On Sunday, January 10, nearly two dozen African American AFL players—with the support of several white teammates—announced that they would leave New Orleans and refuse to play in the All Star game (scheduled for the following weekend) unless the game’s location was changed.

In 1964 and 65 the Civil Rights movement was in full swing, most timelines do not even include this momentous event and its magnitude. The NFL is currently a 9 Billion Dollar industry and in 1965 it was growing at an astonishing rate. The AFL came into the picture in 1960 and employed loads of Black College stars who were great players, it was a game changer. The over-all quality of the game improved and money all of a sudden got HUGE. The AFL instituted innovation and challenged the status quote. New Orleans wanted an NFL or AFL franchise but, was still mired in its old southern, segregationist and racist ways.

Enter the opportunity for New Orleans to showcase itself when the AFL All Star came up for bid, and bid they did and they won the right to host the game. Imagine you are an AFL All Star invited to participate in the All-Star game in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1965. You are told that the event will be a family affair and are encouraged to bring you wife and kids to come with you. You are told that you will be treated like the All-Star you are and will be taken care of in high style. Then, the harsh reality of the south in 1965 hits you when you arrive at the airport, from Oakland California, from Buffalo, New York, from Kansas City, Missouri, San Diego, California and other cities nationwide.

You try to hail a taxi and are treated with insults, called Nig—- and subjected to other indignities. This goes on for hours, and then a cabbie decides to give you a ride. But, instead of taking you to the hotel you’ve instructed him to take you to you are taken to a seedy section of town and told to get the fu– out of the cab. You are threatened and have to walk miles to the hotel carrying your luggage. You check into the hotel and then go out to get a bite to eat; you are turned away from restaurant after restaurant with the slings of verbal abuse. A group of you decide to try again and go out at night and not only are you refused entry into venues; a gun is pulled on one of you as you are escorted out of the bar. How would you feel, was this fair and equitable treatment? This treatment was a far cry from what the promoters of the event and management had conveyed to the players before their arrival to New Orleans.

There were 22 black players invited to participate in this event (game) but one was injured and when home. That left 21 black men in New Orleans ready to play in the game, but after suffering discrimination, overt racism and humiliation they gathered in one room at the Roosevelt Hotel. There was discussion, arguing, and differences of opinion about what they should do as a group. This when on for hours then, the call came to ban together and boycott, this had never been done by professional athletes; Black, or otherwise. The boycott of an event by athletes was unheard of and this would be the first and only boycott of an entire city by a group of athletes.

There were white teammates who would understand what was happening and what their teammates were enduring. The support would come from players who you would not normally think would be supportive. Being a part of a team is a unique and bonding experience, you get to know and love people from many divergent backgrounds. Football is the most physically demanding sport there is and the bonds become life-long no matter what level of play. These warriors banned together and stood against inequity, injustice and for fair treatment.

They were not people with nothing to loose, they had everything to loose. They were jeopardizing their livelihoods, the wrath of the media and fans and their lives. We all understand that being a professional athlete is a shot term career and the window for opportunity is very, very small. They put all of this on the line as a voice for what was right and for those without the power to speak for themselves. In 1965 New Orleans there were separate water fountains, separate schools and restaurants.

After a detailed discussion, the African American players voted to refuse to play in the scheduled game unless it was moved to another city. The protest cut across both racial and team lines, with several white players standing in solidarity with their African American teammates.

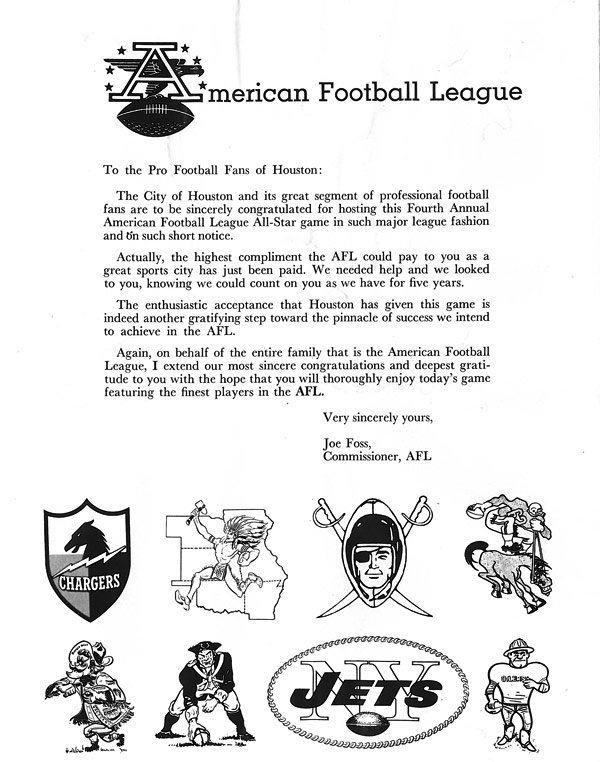

For once, social conscience won out: On January 11, AFL commissioner Joe Foss announced that the game would be held in Houston instead—a city which had reported no discrimination incidents involving athletes in the previous five years. Despite the short notice, the game went off without a hitch, and Foss thanked the people of Houston for their support.

It is difficult to find any good, first-hand information on the situation, and in fact, most record books simply state that the game was played in Houston, and do not even mention that it had to be shifted there at the last minute due to the issues in New Orleans. Fortunately, Ron Mix, called “The Intellectual Assassin,” Hall of Fame tackle with the San Diego Chargers, penned an article for the January 18, 1965, issue of Sports Illustrated, which describes his participation in the boycott. The article, which is titled, “Was This Their Freedom Ride,” is perhaps the best account of the situation and is an important look back at players that have not been given the credit they are due for standing up not only for themselves, but for an entire race.

Cookie Gilchrist of the Bills led the boycott. As he said to Sports Illustrated in 1964, “People think I’m an oddball because I’m a Negro who speak up. But I have a lot on my mind. It’s an internal disease, and it’ll eat me alive if I don’t get it out of my system what I think about things.

The following is an excerpt from “Was This Their Freedom Ride”:

All the Negroes—perhaps 20—crowded into the room, taking seats where they could, some leaning against the wall, most standing. I searched the faces for some clue as to my reception. Some of the faces looked curious; on some was the impatience of a Negro who knows he is going to hear some more of Mister Charlie’s promise of a distant something; a few were unmistakably cold: their minds were set; nothing would change them. Earl turned off the television, and I began:

“Men, I want to talk to you because I feel that what you’re doing is wrong. Some action is necessary, but your method will not do our cause any good. And that cause is to try to rectify all the injustices, to restore dignity to all men. You must look at the overall effects of your action. Will it serve any good to New Orleans? Hell no. The whole city isn’t guilty. Many people here have tried to extend all the courtesies they have control over. They can’t control the feelings and actions of individuals. Do you think that those ignorant individuals who wrong you give a damn whether or not they see a football game? They’ll be glad to see you go. And so what’s been done? Those low-lifes have their way. You’re gone.”

“I feel there are other methods that are better suited for this. We should stay and focus national attention on what is going on. News releases could pour out of here everyday, we could….

“Ron,” interrupted Ernie Warlick, “did it do any good when the Negroes on your team protested their treatment in Atlanta? No, it didn’t. A definite action must be made.”

“Yes, but what good is going to come of it. It’s not going to change the emotions of….”

“Look,” said Art Powell, “we know we aren’t going to change these people. But neither are they going to change us. We must act as our conscience dictates.”

“O.K., Art, what about the thousands of Negroes that can not leave this place? I think that is a bad example for men in your position to set. The place stinks—so you leave.”

“I suppose it would be better to stay here,’ ” Art said, “and by doing so, imply that we accept such treatment for ourselves and our people? Do you want us to condone it?”

I had ignited a fuse. If I had any intention of making progress I would have to change my direction.

“Men, I think you’re all acting in good faith. This whole mess is rotten. I just want you to ask yourselves what effect your action will have on the civil rights cause in the long run. Sure, promises are cheap, but progress is being made. In this very city, too. That we have the game here indicates this.”

“That’s another point,” said Clem. “The promoters for this game assured us that there would be no problems. ‘Bring your wives and children,’ they said. ‘We’re also having a golf tournament.’ It sounded like a big picnic.”

Through all this I noted that Cookie Gilchrist sat bored. He reminded me of a warlord who couldn’t be bothered with the foolish talk of some unaware, uninvolved advisor. His composure suggested that there’s a battle being fought, man; what do you know about it?

I had the feeling that he would rather not listen, rather not be persuaded. I wondered if he and some of the Negroes present were spurred on to this sacrifice because they felt guilty for having escaped the suffering of their southern brother, their ghettoed brother. Now, at last, they had the opportunity to take a stand, to carry their share of the work. Was this their freedom ride? Their Birmingham jail?

“Ron,” said Earl, “I wonder if you are really aware of all that has happened here. It has been quite a bit more than that pool-hall incident in Atlanta.”

Earl began to relate the facts. Others in the room followed suit. When they had finished I knew that I would fail to convince them.

Here are some of the things that had happened: All of the Negroes had trouble securing cabs from the airport to their hotels; one group was stranded there for more than three hours. Another group had been dropped off eight blocks from their destination. Once in the city the cab problem continued.

Abner Haynes asked to go to a certain nightclub and instead was taken to another one a mile away that is a hangout for perverts.

Many players were refused admittance to nightspots.

Ernie Ladd, Dick Westmoreland and a couple of others had been turned away from one Bourbon Street club by a man who indicated he had a gun.

Ernie Warlick was tongue-lashed by a lady who objected when he hung his coat near hers in a restaurant.

All the players, it seemed, had been exposed to varying degrees of indignity.

“No matter how frequently these occurred,” I persisted, though I saw little hope of overcoming such valid emotion, “they are still isolated acts and the whole city cannot be held responsible. What you plan will do harm to yourselves, a great number of innocent people, and to the rights movement in this area. Give us some time to resolve this.”

“Ron,” said Abner, “in 10 minutes, the promoters and some men are going to meet with us. You know what they’re going to tell us? We’re sorry. Stay around, let us work it out. You had trouble with taxis? Well, we’ll round up a car for each of you. What can we do to make it up? I’m afraid, Ron, that they won’t be too convincing. We realize the incidents aren’t their fault. They aren’t ours either. We’ve got to do what we believe is right.”

I left them and walked down the hall to my room. I lay on the bed, feeling very tired. I sympathized greatly with their cause but still felt their methods were wrong, their action too hasty. Perhaps the league office could help. I hoped that the Negro players would give them the opportunity to try.

Late in the afternoon I heard that the meeting between some city representatives and the Negro spokesmen proved uneventful. Many Negro players had left, all would be gone soon.

I made a decision then that if the game were to go on despite the absence of the Negro players, I would not play. I felt I would be wrong in not playing but that it was important for at least one white player—if the game had to be played in New Orleans—to join the Negroes, to say we’re with you. Dammit, I thought again, this time you’re wrong. But your cause is just and we’re with you.

The stand the AFL and its players took against the city of New Orleans was unprecedented. It ultimately brought about change that was necessary in order for the city to get a NFL franchise. That came to fruition two years later when the league granted New Orleans a team.

The boycott was clearly a milestone event that went beyond the world of sports and was more a reflection of American society at the time. It helped shine a spotlight on Congress’s ability to enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and proved that if America was to desegregate, the culture needed to change its mindset and adopt a more progressive view of the human race as quickly as possible.