Ok, let’s talk makeup for us! Very interesting history! This is a long post (4 pages!!) but well worth the read. Enjoy!

When Rihanna launched Fenty Beauty in September, she turned the makeup industry on its head. With its 40 foundation shades — the darkest of which sold out first — Fenty proved that inclusivity in cosmetics is not just ethical but profitable. By serving the customers other mainstream brands have largely ignored, Fenty generated more than $72 million in media value alone the month after its debut.

“I don’t think there was ever such an exciting launch, where a brand received that much excitement and marketing,” says Kimberly Smith, CEO and founder of cosmetics retailer Marjani Beauty. “Now people see it. There’s money to be made by making nuanced shades for women of color.”

But the enormous outpouring of support Fenty has received belies the fact that Rihanna is far from the first entrepreneur to meet the cosmetics needs of women of color. For more than a century, makeup brands have courted the black community and prospered, making it all the more curious that it took 2017’s so-called Fenty effect to confirm the obvious: Women of color enjoy makeup and are eager to buy it.

The first businessperson to successfully tap into this market wasn’t a black woman, but a black man named Anthony Overton. A lawyer who also had a chemistry degree, he opened the Overton Hygienic Manufacturing Co. in Kansas in 1898. The business initially sold baking powder and other products to drug and grocery stores, but Overton recognized that women of color lacked cosmetics that came in their skin tones. The observation prompted his historic foray into makeup.

Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s official cultural historian, points out that access proved to be the major reason black women couldn’t get the makeup they wanted. Samuelson is also writing a book about early black makeup brands.

“Large department stores — they’re not going to stock for people of color,” he says of the early 1900s. “You have to rely on a small network of companies and mail order, so Overton develops a network of salespeople who go out and visit small stores with samples, and also you could send for it by mail.”

Overton Hygenic building in Chicago

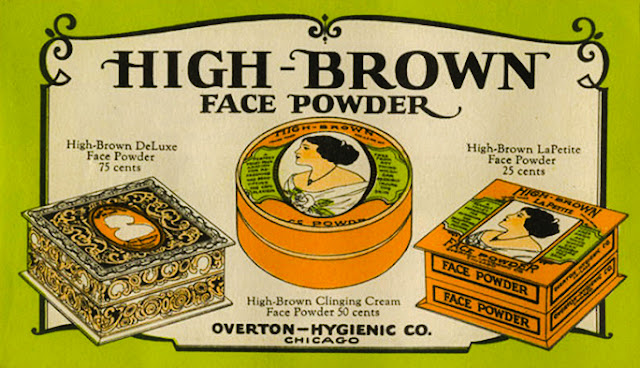

Overton’s “high-brown” face powder created a sensation, with booming sales in the United States and countries like Egypt and Liberia. By the time Overton Hygienic relocated to Chicago’s South State Street in 1911, the company’s sales staff ballooned to 400 and the next year went on to manufacture more than 50 products, including hair creams and eye makeup. The face powder eventually expanded beyond “high brown” to include darker and lighter shades, such as “nut-brown,” “olive-tone,” “brunette,” and “flesh-pink.” In 1920, the company had a Dun & Bradstreet credit rating of $1 million, Jet magazine reported. Ultimately, tapping into this underserved market allowed Overton, born during slavery, to join the elite.

Samuelson credits Overton with transforming the cosmetics industry for black women in every way. Most importantly, his makeup was safe, the historian says.

“A lot of formulations — some would have ground-up chalk and other things in them,” Samuelson says. “In some cases they were actually even dangerous. Overton had strict standards for salespeople and also established a chemical laboratory to test materials out and see if they were safe.”

Overton improved not only makeup formulas for black women, but also how cosmetics for them were packaged. According to Samuelson, he noticed that the few white companies that deigned to serve black customers put products for them in plain black-and-white packaging — inferior wrapping for patrons perceived as inferior. In response, Overton took care to send his products out in beautiful, multicolored containers. In addition to cosmetics, the entrepreneur entered fields like publishing, banking, and insurance. Overton Hygienic stayed in business until 1983, but during its eight-decade span, the company certainly wasn’t the only one selling makeup to black women. (continued)