Flip through early editions of The Crisis, the NAACP’s quarterly magazine, and you’ll see advertisements from Patti’s Beauty Emporium for “Brazilian toilette luxuries.” The mail-order business sold perfumes, creams, and Patti’s “La Traviata” face powder for 68 cents. But who was Patti? The name of the face powder provides a clue.

Anita Patti Brown

”La Traviata” is an 1853 opera by Giuseppe Verdi, and Patti was Anita Patti Brown, an African-American soprano known as the “Bronze Tetrazzini” to liken her to Italian soprano Luisa Tetrazzini. The black press also nicknamed her the “globe-trotting prima donna” due to her nonstop touring schedule. Samuelson calls Brown the Rihanna of her day.

“What Rihanna is doing is the same thing Anita Patti Brown was doing — using her fame to get these products made,” he says. “She was a great operatic concert star, but due to matters of race, she played small venues. She did have considerable name recognition and fame within the black community. She was well covered in the black newspapers.”

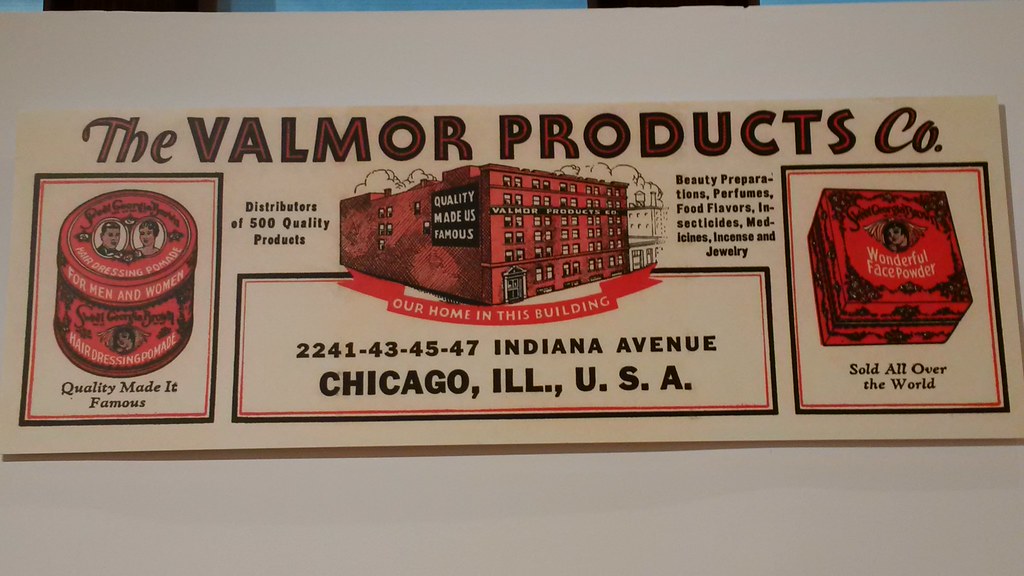

But her cosmetics venture fizzled out after a few years. At the time, black women entrepreneurs such as Madam C.J. Walker, Sarah Spencer Washington, and Annie Turnbo Malone achieved success by focusing primarily on hair care and just dabbling in makeup. Another man, however, would enjoy immense success with a cosmetics company that courted African Americans. Morton Neumann, a Hungarian American who grew up in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, knew that cosmetics companies marginalized black clients. Like Overton, Neumann had a chemistry background, and in 1926 he established his own business, Valmor Products Co., which largely targeted black customers. They especially took to Valmor’s Sweet Georgia Brown face powder, then available for 60 cents in colors like “tantalizing dark brown,” “aristocratic brown,” “sun-tan,” and “teezum [tease ’em] red.”

Note the colorism in one ad for the face powder. It promised a “lighter appearance in 10 seconds” and pointed out that the powder “is specially made to give tan and dark complexions the BRIGHTER attractive beauty that everybody admires.”

Hubert Neumann, 86, remembers his father hawking products to people both in and outside the black community. The businessman may have gravitated toward makeup after working for a manufacturer that sold face soap and shampoo, according to his son.

“One day somebody noticed that a lot of people in rural places don’t have access to cosmetics, and a good portion of them were black,” Neumann says.

He describes his father as an entrepreneur of all trades. Having a number of revenue streams kept him in business for decades.

“He had hair products,” Neumann recalls. “He sold wigs. He had jewelry. He sold novelties. He sold books. He sold a lot of things.”

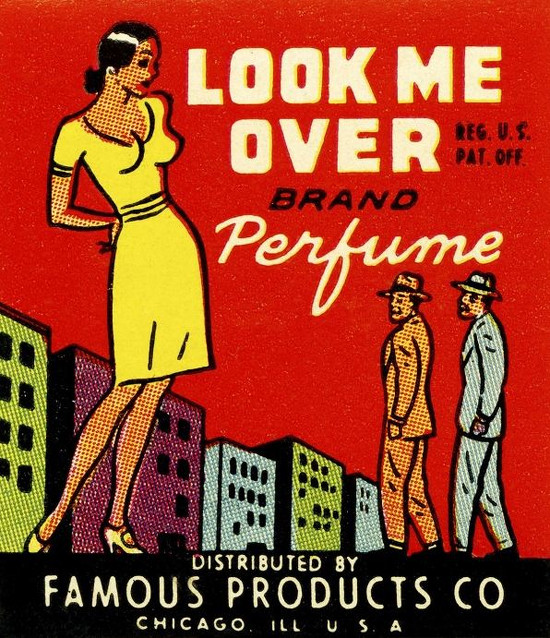

Neumann also recalls the attention his father gave to the graphic art on Valmor products. Morton Neumann hired highly trained black artists like Charles Dawson and Jay Jackson. A graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, Dawson set out to depict African Americans with dignity on the merchandise. They didn’t look like racial caricatures with funhouse facial features. Instead, they appeared well-groomed, well-dressed, and sometimes undressed — depending on the product advertised. Many ads coupled flirty-sounding products like “Hug Me Tight” sachet powders and “Hold Your Man” perfume with renderings of racially ambiguous women giving come-hither looks. Featuring ethnically indeterminate women in ads reportedly helped the company appeal to a cross section of customers.

Given the thread of sexual innuendo in the marketing, however, the artists may have also drawn on antebellum stereotypes that framed mixed-race women as either sexually desirable, oversexed, or both. And the prevailing colorism of the day meant that although Sweet Georgia Brown face powder came in “tantalizing dark brown,” none of the women illustrated in the artwork ever appeared darker than a paper bag.

Valmor artists didn’t get credit for their provocative and innovative work — in pop art style well before Andy Warhol made it mainstream. But their illustrations garnered fans, including filmmaker Terry Zwigoff and the Rolling Stones. Zwigoff traveled to the Valmor offices in 1974 to acquire buy viagra 25mg some of the artwork. Four years later, the Stones imitated Valmor’s ads for its Some Girls album cover. Samuelson might just be the biggest fan of Valmor’s merchandising. In 2015, he curated the Chicago Cultural Center exhibition “Love for Sale: The Graphic Art of Valmor Products.” It gave the black artists behind the ads the due they didn’t receive in life.

While Chicago companies like Overton Hygienic and Valmor dominated the African-American cosmetics industry, they did have competition from other cities. In 1923, for example, two white, Jewish chemists — Morris Shapiro and Joseph Menke — opened Keystone Laboratories in Memphis. The men later split up, and Shapiro launched Lucky Heart Laboratories in 1935. A vintage Lucky Heart ad noted that “Lucky Heart Cosmetics are not sold in stores, only by Representatives.” It was a polite reference to the department-store racism that barred black products and people. Brands like Lucky Heart relied on sales reps, often ordinary community members, to show the cosmetics “to friends, neighbors, people you know at work, church or in social groups.” (continued)