Both Keystone and Lucky Heart are still in business today. They primarily sell hair and skincare products, with some relics of the past, such as Lucky Heart’s beauty bleaching cream. Lucky once offered makeup products like tint cream and a Color-Keyed Cosmetics line. However, another Memphis cosmetics business, the Hi-Hat Company, prided itself on offering “smart shades for every complexion.” Hi-Hat’s Jockey Club face powder came in hues such as “Harlem tan,” “Spanish rose,” “chocolate brown,” and “copper bronze.”

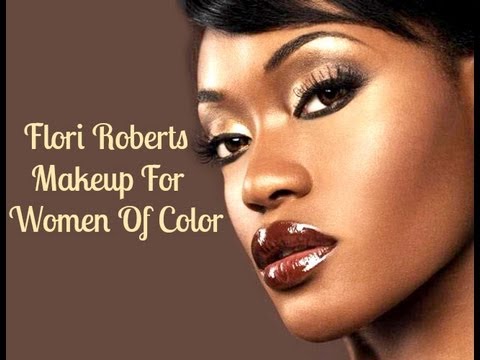

As the civil rights movement sparked social change that led to the desegregation of makeup counters and higher incomes for black families, the niche businesses that served women of color began to compete for customers with mainstream brands like Maybelline and Avon. In fact, Avon began using black models in its Ebony magazine ads in 1961, according to Susannah Walker’s book Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women. The book points out that during the five years that ended the 1960s, a half-dozen cosmetics lines for black women debuted. One of them, Flori Roberts, bills itself as the first such line that department stores carried.

Patrice Grell Yursik, creator of the beauty blog Afrobella.com, knows the brand well. “I’m from the Caribbean, and I’ve used Flori Roberts, which was a white woman who made makeup intended for women of color,” she says. “Then there was Fashion Fair, part of Ebony magazine and the Johnson Publishing Company. They were historic brands that catered to women of color.”

In 1973, Johnson Publishing launched Fashion Fair Cosmetics. Fifteen years earlier, the company started an annual fashion show featuring black designers and models. But finding suitable makeup for the models always proved difficult, so Johnson Publishing CEO John H. Johnson and wife, Eunice, resolved to start their own line. According to African-American Business Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary, Johnson first approached major cosmetics companies like Revlon about expanding their makeup to better serve black women, but they passed. Since the oldest black makeup brands operated by mail order, with roving sales reps to show off products, it was all too easy for major manufacturers to assume that no market for women of color existed.

Desiree Reid, general manager of Impala Inc., parent company of IMAN Cosmetics, says that myths about black women and makeup have circulated for years.

“They don’t wear makeup. They don’t do this. They don’t do that,” Reid says corporations have argued. “There have been myths about how we engage with makeup and what kind of makeup. They never thought of us as part of that conversation. But if you speak to any woman of color, her parents and grandparents, there was never a time where we didn’t wear makeup. I don’t remember a time where anybody — my aunt, who’s 87; my mother, who’s 80 years old — didn’t go out without putting on some powder, blush, and a little mascara.”

Major manufacturers may have dismissed the Johnsons, but the couple didn’t let the rejection deter them. They visited a laboratory to concoct makeup batches. They tried out the formulas on their models, and Fashion Fair was born. Determined to make the brand upscale, Johnson approached department stores such as Marshall Field’s, Bloomingdale’s, Neiman Marcus, and Dillard’s about stocking Fashion Fair. They agreed, and by the late 1980s, more than 1,500 stores carried the brand.

Makeup artist Zarielle Washington, 32, says Fashion Fair was one of the first brands she wore growing up. She remembers sneaking on her grandmother’s Fashion Fair products and also buying drugstore brands such as Zuri, Black Opal, and Black Radiance. She’s from Memphis, where she says women put on makeup simply to go grocery shopping.

Washington calls Fashion Fair an African-American cosmetics pioneer. She knows the challenges Eunice Johnson faced to get corporations to recognize black women as consumers.

“You have to have people speak up and lobby for things and create their own,” she says. “Sometimes companies don’t want to change, and I think that’s a huge problem. Women of color around the world are being left out of the beauty sector.” (continued)