In January 1967, a 22-year-old Emory Douglas met Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver, the Ministers of Defense and Information of the Black Panther Party, a moment which set the course for a life in revolutionary art. Douglas strongly identified with the Black Panther’s assertive response to injustice. He respected the non-violent actions of Dr. Martin Luther King, but he was among the many young victims of racial inequality who wanted to push harder.

Douglas met the Panthers in Oakland, just as they were working on the first issue of the party’s newsletter, cobbling together four pages using a typewriter and copy machine.

He had been introduced to graphic design at a young age at a print shop in juvenile detention. Later, he honed his skills in the reputable commercial art program at San Francisco City College, where he learned the fundamentals of figure drawing, lettering, prepress operations, design, and filmmaking.

Watching that scene in Cleaver’s studio apartment, Douglas immediately saw an opportunity to take part in the movement. He offered to run home and get some supplies to help make the paper look more professional. By the time he returned they had finished that first issue, but Douglas got to work on the next one and hundreds that followed.

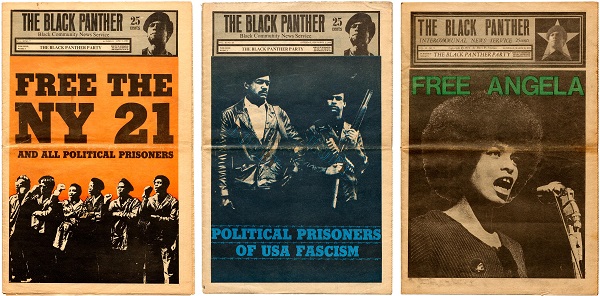

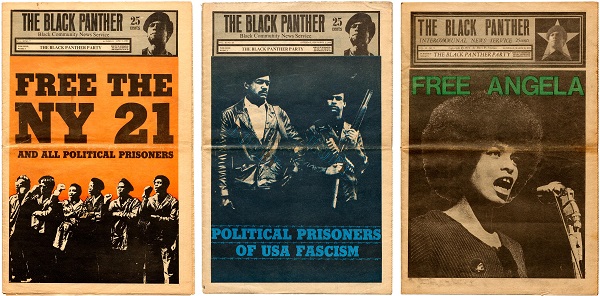

He was soon conscripted to become the party’s Minister of Culture and Revolutionary Artist, responsible not only for the production of The Black Panther, but also the posters wheatpasted on the streets of Oakland and San Francisco, and the leaflets and pamphlets that were eventually distributed to minority communities throughout the country. His work became the visual identity of the Black Panther Party.

Each weekly issue of the “Black Community News Service” shone a light on the black struggle, educated and organized the community, and promoted the party’s platform, the Ten-Point Program, which demanded full employment, decent housing, education, and health care. There were news stories and critical essays from party leaders, but it was Douglas’s graphical contribution, in the form of cartoons, collages, and a full page illustration on each back cover, that struck a chord with the broadest audience.