Good Morning Obots!!

I do believe we have what could be the makings of a very good movie with our feature today (not that the others wouldn’t make great screen stories as well).

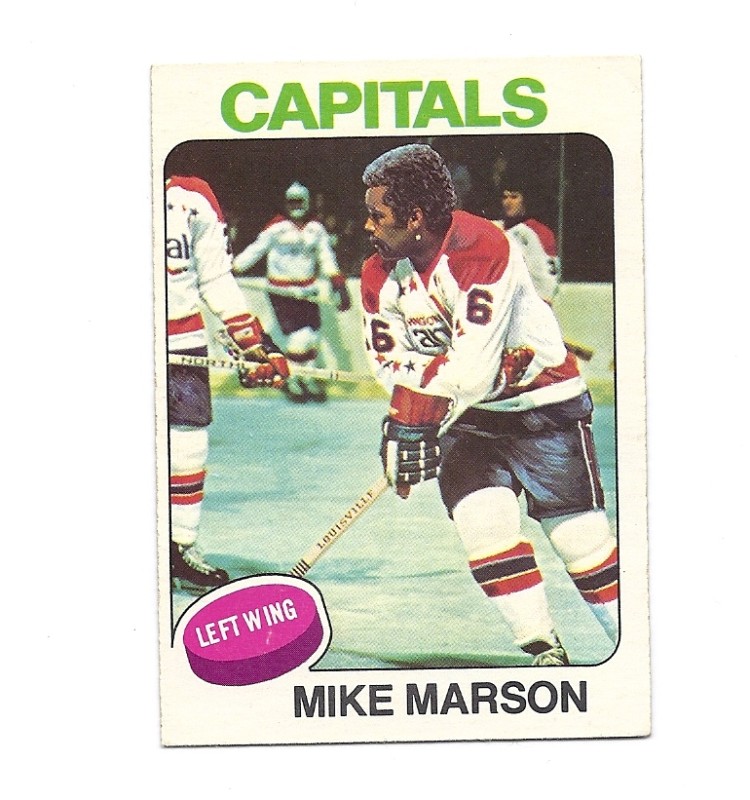

Mike Marson

A decade and a half after Willie O’Ree broke hockey’s color barrier, Mike Marson became just the second black hockey player in National Hockey League history.

Marson came along as a highly touted kid from Scarborough, Ontario. He was so talented that age 16 he joined the OHL’s Sudbury Wolves after being the 4th overall draft pick in the entire province. He became a junior standout, serving as tough guy, leading scorer and team captain of a Wolves team also sporting luminaries Ron Duguay, Dave Farrish, Eric Vail and Randy Carlyle. So impressive was he that the NHL’s Washington Capitals used the 19th overall pick in the 1974 draft to grab him, just a few picks ahead of Bryan Trottier, Mark Howe, Tiger Williams, Danny Gare and Guy Chouinard.

Unfortunately for Marson, he was not able to translate his excellent amateur resume into NHL success, largely due to several reasons, but mostly because he was not able to handle the political pressures associated with racism.

Just 5’9″ tall, he often played well over 200lbs. The Capitals felt this affected his skating ability and therefore his ability to be an effective hockey player and not just a tough guy. His teammates teased him relentlessly about his weight, something that always bothered him. As a result he never really felt accepted by many of his own teammates.

Bill Riley, the third black in the NHL and Marson’s soon to be teammate, said Marson didn’t do himself any favors when he chose to rarely associate himself with teammates away from the rink. Rather than engaging himself in common team building social activities he enrolled for part time courses at the University of Maryland and voraciously read about philosophies of Mao, Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King.

Another reason was he was admittedly rushed into the NHL. The Capitals were hockey’s worst team, desperately needing a transfusion of new blood. The NHL had just lowered the eligible age level to 18, and the Caps promoted him directly to the NHL. With the benefit of hindsight, Marson himself agrees he made the jump to early.

“A rookie should never go from the juniors straight to the National Hockey League without take a course in life management skills.”

But the biggest problem for Marson was the racism he had to endure. No course in life management skills could have likely prepared Marson for what he had to endure. Not that a course may have helped. Marson was bullheaded and refused to bend, which led to him becoming a bitter and angry young man who never enjoyed the sport the same way he did back in Sudbury or as a youth.

“For me the biggest problem was that I was naive,” Marson told Cecil Harris, author of Breaking The Ice, a book about blacks in the NHL. “I watched the assassinations of Martin Luther King and the Kennedys in the sixties, as everybody did. But I believed coming through the hippie era in the sixties and seventies that the world was a better place and people had evolved to where you could love your fellow man and woman regardless of race, creed or color. I mean, I really believed that. I believed that to the point of being radically naive.

Although he and his family undoubtedly dealt with racism for a long time, Marson’s upbringing in small town Canada probably sheltered him from the realities of America at the time.

“For me, it seemed normal to be a hockey player. I grew up in Canada. I played hockey. A black hockey player? So what? But I found out that people looked at me like I was a Martian. Not Mike Marson. Mike Martian. Because I was a black hockey player.”

The naive and cradled Marson was thrust into the heart of racial unrest in Washington, D.C. Making headlines as hockey’s first black superstar, both sides wanted to use him or at least his image. To make matters worse, the non-conforming Marson didn’t make things easier for himself. Sporting a big afro and Fu-Manchu moustache at a time when such hairstyles were very much a political statement, he dated and married a white woman when inter-racial marriage was still a no-no. No matter what he did the political pressure came from both whites and blacks, and the taunts, including death threats, were too much for him to take.

In his book Harris writes of Marson as the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. Marson should have become one of the top players in the National Hockey League. But he was unable truly focus on hockey.

“There was just so much garbage I had to deal with that I just wasn’t used to,” he said. “The accumulation of all that garbage just made me uneasy. Uncomfortable all the time. How can you perform at your best as a professional athlete if you’re uncomfortable all the time? You can’t. It’s impossible.”

He tried. He had a decent rookie season, scoring 16 goals and establishing himself as a feared fighter. But his production slipped, and he was demoted to the minor leagues just 3 years later. Tired of dealing with everything, including increasing levels of depression and drinking, he quit hockey at the age of 25.

“I saw myself as a hockey player. Everybody else saw me as different.”

Marson returned to southern Ontario, and worked as a bus driver in Toronto. He found refuge and peace in martial arts. Marson became a 5th degree black belt in the Japanese style of Shotokan, attaining the status of Master-Shihan. Now some 250 pounds, the always intimidating Marson combined knowledge of hockey and martial arts to create Mike Marson’s Athletic Training Services. Also offering motivational speeches, he’s developed an off-ice training program for hockey players that gives players a better awareness of timing and focus through an understanding of the martial arts. Among his students is NHL superstar Rick Nash.