GOOD MORNING P.O.U.!

We continue our series on Black Shakespearean Actors…

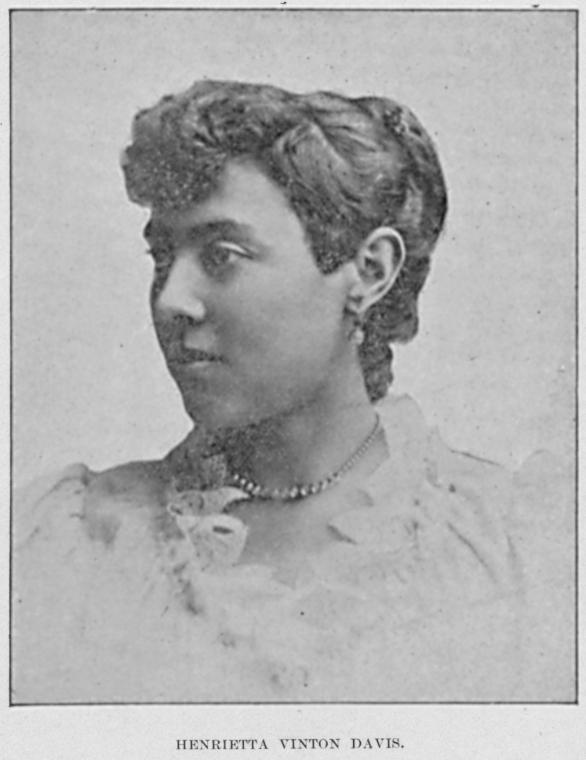

HENRIETTA VINTON DAVIS

(1860-1941)

(From Baltimore City Paper)

The Lady Vanishes

Meet Henrietta Vinton Davis-one of the most amazing women you’ve probably never heard of

By Lee Gardner | Posted 8/4/2010

[…]Born in Baltimore in 1860, she moved to Washington, D.C., as a girl, and as a young woman launched a career as an actress and elocutionist. For more than 25 years, she criss-crossed the United States and the Caribbean, performing everything from Shakespeare—she is purportedly the first African-American woman to do so—to the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar and winning acclaim from audiences and press, both black and white alike. And then, approaching her 60th birthday, she traded acting for activism and put her skills to use in the service of Marcus Garvey, his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and the causes of black nationalism and pan-African liberation. Though she eventually fell out with Garvey, she devoted her life to black nationalist causes until her death in 1941.

[…]Only three things are known about Henrietta Vinton Davis’ father. His name was Mansfield Vinton Davis, he was a musician, and he died sometime around the time his daughter was born. Henrietta’s mother, the former Mary Ann Johnson, was left a teenage widow with a child to raise. She quickly remarried, to a businessman named George A. Hackett.

According to Leroy Graham’s book Baltimore: The 19th Century Black Capital, Hackett was as well-known and respected as any black man in Baltimore at that time, with the possible exception of his friend and associate Frederick Douglass. In 1860, the year Henrietta was born, Hackett was in the thick of a fight against a piece of state legislation known as the Jacobs Bill. Put forth by Eastern Shore legislator C.W. Jacobs in reaction to John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid the year before, the bill proposed that all adult blacks in the state—including Maryland’s sizeable free black population—be deported to Africa and that all black children in the state be enslaved, including those who had been born free. Hackett rallied opposition to the bill, circulating petitions and delivering speeches. Though the legislature actually passed it, the measure failed in a statewide referendum.

Thus Davis grew up in a household where success, political engagement, and racial pride were cornerstones. After Hackett died in 1870, Mary Ann moved with her preteen daughter to Washington. Davis attended public school and went on to become certified as a teacher in Maryland. She moved to Louisiana and taught there for several years, but returned to Washington and took a job at the federal Office of the Recorder of Deeds in 1878—the first black woman employed by the office.

Davis apparently took an interest in acting and elocution. The latter was both a discipline—elocution teachers taught proper pronunciation, voice projection, breath control, etc.—and a form of entertainment, as people filled 19th-century theaters and halls to hear speakers deliver poetry, dramatic monologues, and famous speeches. Davis studied with white Washington elocutionist Marguerite Saxton as well as elocutionists in Boston and New York.

[…]Scant details survive of how Davis made the leap from paper shuffling to the professional stage. But historians know that Davis’ family friend Frederick Douglass took over the Office of the Recorder of Deeds in 1881.

Soon after LeBouef discovered Davis’ story, he shared it with the creative staff at CenterStage, and the theater later commissioned him to write a play about her. Researching Davis’ life as best he could and taking dramatic license with the rest, LeBouef emerged with Shero: The Livication of Henrietta Vinton Davis. (CenterStage subsequently hosted a reading of the play, but never produced it.) In the play, Douglass happens upon Davis practicing her Shakespeare around the office and takes her under his wing.

While there’s no historical evidence to back up such a scenario, on April 25, 1883, Douglass did introduce Davis at her first public recital  (including speeches from Romeo and Juliet and The Merchant of Venice) before an audience of both blacks and whites at Washington’s Marini Hall. Black newspaper The Washington Bee reported that Davis “wrapped the whole audience so close to her that she became a queen of the stage in their eyes.”

(including speeches from Romeo and Juliet and The Merchant of Venice) before an audience of both blacks and whites at Washington’s Marini Hall. Black newspaper The Washington Bee reported that Davis “wrapped the whole audience so close to her that she became a queen of the stage in their eyes.”

Davis’ sideline as an actress and elocutionist was soon so successful that she quit the Office of the Recorder of Deeds in 1884. (She also married her manager, an erstwhile singer named Thomas Symmons, though the marriage apparently didn’t last.) She made frequent appearances in Washington, Philadelphia, New York, and Cleveland, eventually pushing out from the major East Coast cities to include tours of the West and Northwest. She added Lady Macbeth, Cleopatra, and others to her Shakespearean repertoire, but also recited Paul Laurence Dunbar’s dialect poem “Little Brown Baby.” She often appeared with other black actors, performing Shakespearean scenes, and starred in full-fledged productions of other works with black theater companies as well. She formed her own company to mount a touring production of a contemporary drama about the Haitian revolution entitled Dessalines, and co-wrote and played the lead role in a drama called Our Old Kentucky Home. She also began appearing outside the United States, performing in Cuba, Jamaica, and Central and South America.

In short, Davis was an international star. Despite occasional mixed reviews, her acting won praise and packed houses wherever she went. As the Buffalo Sunday Truth noted, she was “a singularly beautiful woman, little more than a brunette, certainly no darker than a Spanish or Italian lady in hue.” And yet, her African heritage kept her locked out of the mainstream (read: white) professional theater of the time. As busy as she was, her opportunities were nonetheless limited.

[…]Davis’ interest in politics surfaced during her acting career. She so identified with the cause of the Populist Party, a short-lived progressive third party built on a base of farmers and aligned against the power and wealth of the Eastern elites, that she wrote party leader Ignatius Donnelly several times in 1892 to offer her services as a speaker, touting her “eagerness to serve my race and humanity.” And in the early 1910s, during her travels to Jamaica, she encountered Marcus Garvey.

[…]Exactly how Davis came to join Garvey’s cause is uncertain, but she spoke on his behalf at a gathering in Harlem in 1919 and was soon an important member of his fledgling U.S. organization. According to a 1983 account of Davis’ career researched and written by historian William Seraile (which Azikiwe has posted on his blog, henriettavintondavis.wordpress.com), Davis was one of 13 charter members of the U.S. iteration of the UNIA, and was among the signers of the 1920 Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World. She was bestowed several important titles and duties in the UNIA, but the one that best defined her work over the next dozen years was “international organizer.”

“She was evidently a great speaker,” says Seraile, a professor emeritus at Lehman College in the Bronx, N.Y., in a phone interview. “And she was a drawing card for Garvey. A lot of people came out to hear her speak because of her theatrical background.”

Davis went back on tour, this time using her star power and elocution skills to recruit new members to the UNIA and Garvey’s cause. Traveling throughout the United States and Caribbean Basin, “Lady Vinton” railed against the term “colored” and advocated the more self-empowered term “Negro.” She proclaimed to the audiences who gathered to hear her that Garvey was “a man chosen by God to lead his people.” She hammered home the UNIA’s message of black separatism and political and economic self-reliance; according to Seraile’s research, she told an audience in New York that “as long as we depend upon the white man for a job, so long we will be his football.” Though in her 60s, she spent months traveling through the humid tropics and exhorting the assembled crowds.

“This lady’s in Liberia,” LeBouef says. “This lady’s raising money and buying [ships] with Garvey and traveling to Cuba. This lady’s talking about African liberation, [and] black people just a few years out of enslavement owning shit. These people were not playing.”

The Garvey movement certainly captured the attention of white authorities. In 1922, Garvey was arrested by the FBI and slapped with charges of mail fraud in relation to his attempts to raise funds for his Black Star Line. He was tried and convicted and sentenced to five years in prison.

Davis continued to speak on his behalf, and on behalf of the UNIA, but internal dissension began to weaken the movement as much as external pressures. The UNIA lost members in droves. In 1927, Garvey was deported to Jamaica and Davis was one of his few U.S. supporters who followed him into exile, remaining by his side as he started a new iteration of his still extant organization, which he dubbed the UNIA of the World.

“I think she believed in the cause, like a lot of people did at the time,” Seraile says. “Even in ’24 or ’25, when a lot of people started to desert, she was out there lecturing, telling people to stick with Garvey, stick with the message.”

But Davis’ dogged loyalty found its limits. Whether because of the tensions generated by the rift between Garvey’s UNIA in exile and the U.S. UNIA, or because of some more personal reason, she eventually returned home to the United States. In 1934, she even became president of what was left of the stateside UNIA for a time. “She was almost 80 years old, but she still made a big impression on people,” Nnamdi Azikiwe says. Still, Davis had been in poor health for years. At some unknown point, her association with the UNIA ended, and she died on Nov. 23, 1941.

Seraile unearthed a 1921 quote from The Negro World, the UNIA newspaper, that said of Davis “when the history of this giant movement shall have been written, [her name] shall be emblazoned in letters of gold as the lady, the stateswoman, and the diplomat.” But that’s obviously not what happened.