Good Morning POU! We continue looking at Afrofuturists and their impact on our culture. Today, we look at one of the most prolific and well-known authors of Afrofuturism – the one and only Octavia Butler.

Octavia Estelle Butler (June 22, 1947 – February 24, 2006) was an American science fiction writer. A multiple recipient of both the Hugo and Nebula awards, in 1995 she became the first science fiction writer to receive the MacArthur Fellowship.

Growing up in the racially integrated community of Pasadena allowed Butler to experience cultural and ethnic diversity in the midst of racial segregation. She accompanied her mother to her cleaning work and where the two entered white people’s houses through back doors.

“I began writing about power because I had so little.”Octavia E. Butler, in Carolyn S. Davidson’s “The Science Fiction of Octavia Butler.”

From an early age, an almost paralyzing shyness made it difficult for Butler to socialize with other children. Her awkwardness, paired with a slight dyslexia that made schoolwork a torment, led her to believe that she was “ugly and stupid, clumsy, and socially hopeless,” becoming an easy target for bullies. As a result, she frequently passed the time reading at the Pasadena Central Library and writing reams and reams of pages in her “big pink notebook”. Hooked at first on fairy tales and horse stories, she quickly became interested in science fiction magazines such as Amazing Stories, Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and began reading stories by John Brunner, Zenna Henderson, and Theodore Sturgeon.

At age 10, she begged her mother to buy her a Remington typewriter on which she “pecked [her] stories two fingered”. At 12, watching the televised version of the film Devil Girl from Mars (1954) convinced her she could write a better story, so she drafted what would later become the basis for her Patternist novels. Happily ignorant of the obstacles that a black female writer could encounter, she became unsure of herself for the first time at the age of 13, when her well-intentioned aunt Hazel conveyed the realities of segregation in five words: “Honey … Negroes can’t be writers.” Nevertheless, Butler persevered in her desire to publish a story, even asking her junior high school science teacher, Mr. Pfaff, to type the first manuscript she submitted to a science fiction magazine.

After graduating from John Muir High School in 1965, Butler worked during the day and attended Pasadena City College (PCC) at night. As a freshman at PCC, she won a college-wide short story contest, earning her first income ($15) as a writer. She also got the “germ of the idea” for what would become her novel Kindred, when a young African-American classmate involved in the Black Power Movement loudly criticized previous generations of African Americans for being subservient to whites. As she explained in later interviews, the young man’s remarks instigated her to respond with a story that would give historical context to that shameful subservience so that it could be understood as silent but courageous survival. In 1968, Butler graduated from PCC with an associate of arts degree with a focus in History.

Rise to Success

Success continued to elude her, as an absence of useful criticism led her to style her stories after the white-and-male-dominated science fiction she had grown up reading. She enrolled at California State University, Los Angeles, but then switched to taking writing courses through UCLA Extension.

During the Open Door Workshop of the Screenwriters’ Guild of America, West, a program designed to mentor minority writers, her writing impressed one of the teachers, noted science-fiction writer Harlan Ellison. He encouraged her to attend the six-week Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop in Clarion, Pennsylvania. There, Butler met the writer and later longtime friend Samuel R. Delany. She also sold her first stories: “Child Finder” to Ellison, for his anthology The Last Dangerous Visions (still unpublished), and “Crossover”to Robin Scott Wilson, the director of Clarion, who published it in the 1971 Clarion anthology.

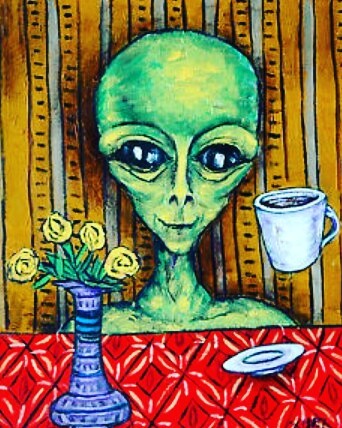

For the next five years, Butler worked on the series of novels that later become known as the Patternist series: Patternmaster (1976), Mind of My Mind (1977), and Survivor (1978). In 1978, she was finally able to stop working at temporary jobs and live on her writing. She took a break from the Patternist series to research and write Kindred (1979), and then finished the series with Wild Seed (1980) and Clay’s Ark (1984).

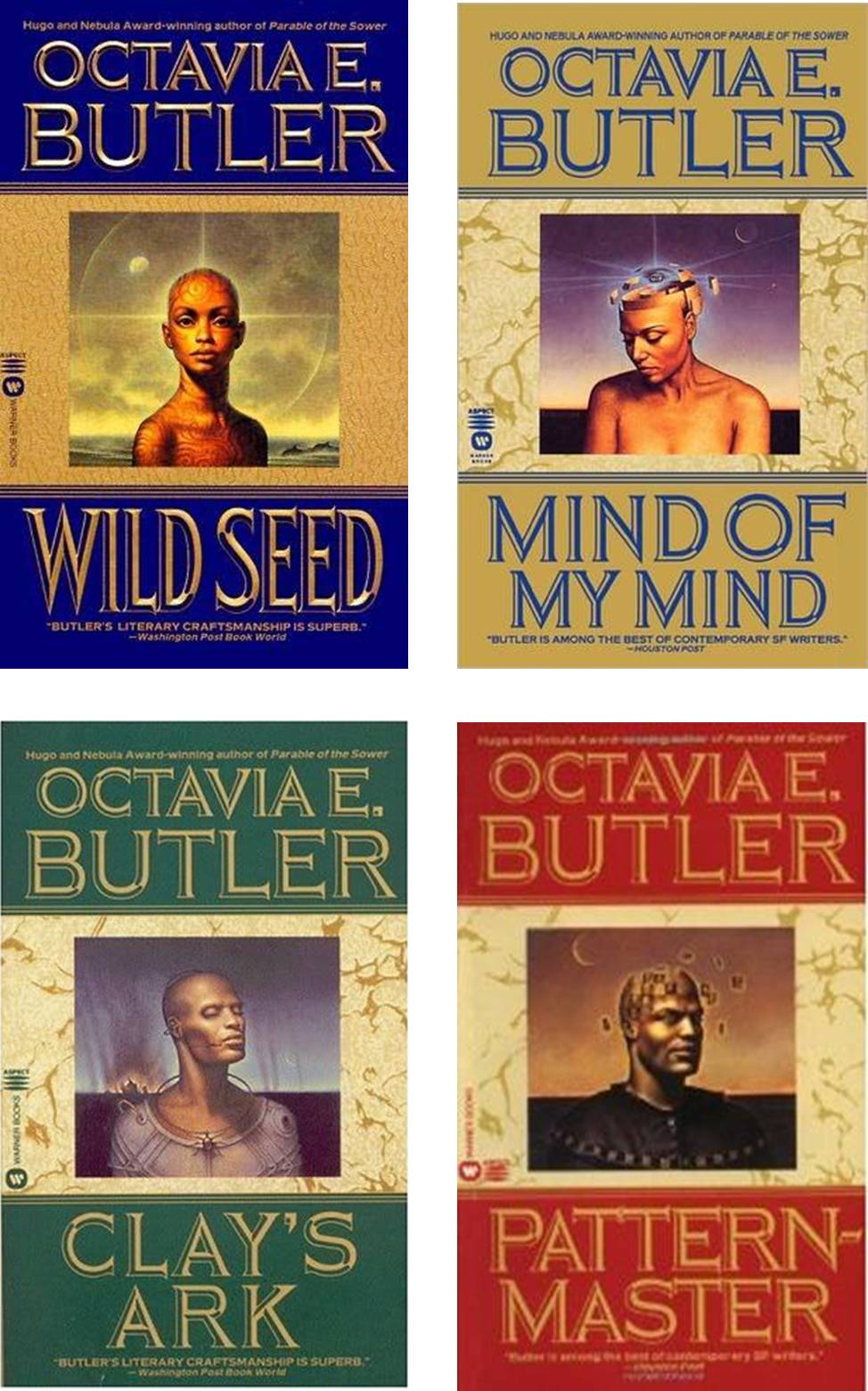

Butler’s rise to prominence began in 1984 when “Speech Sounds” won the Hugo Award for Short Story and, a year later, Bloodchild won the Hugo Award, the Locus Award, and the Science Fiction Chronicle Reader Award for Best Novelette. In the meantime, Butler traveled to the Amazon rainforest and the Andes to do research for what would become the Xenogenesis trilogy: Dawn (1987), Adulthood Rites (1988), and Imago (1989). These stories were republished in 2000 as the collection Lilith’s Brood.

During the 1990s, Butler worked on the novels that solidified her fame as a writer: Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). In 1995, she became the first science-fiction writer to be awarded a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation fellowship, an award that came with a prize of $295,000.

Her Works – The Patternist Series, Kindred

Butler’s first work published was Crossover in the 1971 Clarion Workshop anthology. She also sold the short story Childfinderto Harlan Ellison for the anthology The Last Dangerous Visions. “I thought I was on my way as a writer,” Butler recalled in her short fiction collection Bloodchild and Other Stories. “In fact, I had five more years of rejection slips and horrible little jobs ahead of me before I sold another word.”

Starting in 1974, Butler worked on a series of novels that would later be collected as the Patternist series, which depicts the transformation of humanity into three genetic groups: the dominant Patternists, humans who have been bred with heightened telepathic powers and are bound to the Patternmaster via a psionic chain; their enemies the Clayarks, disease-mutated animal-like superhumans; and the Mutes, ordinary humans bonded to the Patternists.

The first novel, Patternmaster (1976), eventually became the last installment in the series’ internal chronology. Set in the distant future, it tells of the coming-of-age of Teray, a young Patternist who fights for position within Patternist society and eventually for the role of Patternmaster.

Next came Mind of My Mind (1977), a prequel to Patternmaster set in the twentieth century. The story follows the development of Mary, the creator of the psionic chain and the first Patternmaster to bind all Patternists, and her inevitable struggle for power with her father Doro, a parapsychological vampire who seeks to retain control over the psionic children he has bred over the centuries.

The third book of the series, Survivor, was published in 1978. The titular survivor is Alanna, the adopted child of the Missionaries, fundamentalist Christians who have traveled to another planet to escape Patternist control and Clayark infection. Captured by a local tribe called the Tehkohn, Alanna learns their language and adopts their customs, knowledge which she then uses to help the Missionaries avoid bondage and assimilation into a rival tribe that opposes the Tehkohn.

After Survivor, Butler took a break from the Patternist series to write what would become her best-selling novel, Kindred (1979) as well as the short story “Near of Kin” (1979). In Kindred, Dana, an African-American woman, is transported from 1976 Los Angeles to early nineteenth century Maryland. She meets her ancestors: Rufus, a white slave holder, and Alice, a black freewoman forced into slavery later in life. In “Near of Kin” the protagonist discovers a taboo relationship in her family as she goes through her mother’s things after her death.

In 1980, Butler published the fourth book of the Patternist series, Wild Seed, whose narrative became the series’ origin story. Set in Africa and America during the seventeenth century, Wild Seed traces the struggle between the four-thousand-year-old parapsychological vampire Doro and his “wild” child and bride, the three-hundred-year-old shapeshifter and healer Anyanwu. Doro, who has bred psionic children for centuries, deceives Anyanwu into becoming one of his breeders, but she eventually escapes and uses her gifts to create communities that rival Doro’s. When Doro finally tracks her down, Anyanwu, tired by decades of escaping or fighting Doro, decides to commit suicide, forcing him to admit his need for her.

In 1983, Butler published “Speech Sounds,” a story set in a post-apocalyptic Los Angeles where a pandemic has caused most humans to lose their ability to read, speak, or write. For many, this impairment is accompanied by uncontrollable feelings of jealousy, resentment, and rage. “Speech Sounds” received the 1984 Hugo Award for Best Short Story

In 1984, Butler released the last book of the Patternmaster series, Clay’s Ark. Set in the Mojave Desert, it focuses on a colony of humans infected by an extraterrestrial microorganism brought to Earth by the one surviving astronaut of the spaceship Clay’s Ark. As the microorganism compels them to spread it, they kidnap ordinary people to infect them and, in the case of women, give birth to the mutant, sphinx-like children who will be the first members of the Clayark race.

Bloodchild and the Xenogenesis trilogy

Butler followed Clay’s Ark with the critically acclaimed short story “Bloodchild” (1984). Set on an alien planet, it depicts the complex relationship between human refugees and the insect-like aliens who keep them in a preserve to protect them, but also to use them as hosts for breeding their young. Sometimes called Butler’s “pregnant man story,” “Bloodchild” won the Nebula, Hugo, and Locus Awards, and the Science Fiction Chronicle Reader Award.[17]

Three years later, Butler published Dawn, the first installment of what would become known as the Xenogenesis trilogy. The series examines the theme of alienation by creating situations in which humans are forced to coexist with other species to survive and extends Butler’s recurring exploration of genetically-altered, hybrid individuals and communities. In Dawn, protagonist Lilith Iyapo finds herself in a spaceship after surviving a nuclear apocalypse that destroys Earth. Saved by the Oankali aliens, the human survivors must combine their DNA with an ooloi, the Oankali’s third sex, in order to create a new race that eliminates a self-destructive flaw in humans—their aggressive hierarchical tendencies. Butler followed Dawn with “The Evening and the Morning and the Night” (1987), a story about how certain female sufferers of “Duryea-Gode Disease,” a genetic disorder which causes dissociative states, obsessive self-mutilation, and violent psychosis, are able to control others afflicted with the disease.

Adulthood Rites (1988) and Imago (1989) the second and the third books in the Xenogenesis trilogy, focus on the predatory and prideful tendencies that affect human evolution, as humans now revolt against Lilith’s Oankali-engineered progeny. Set thirty years after humanity’s return to Earth, Adulthood Rites centers on the kidnapping of Lilith’s part-human, part alien child, Akin, by a human-only group who are against the Oankali. Akin learns about both aspects of his identity through his life with the humans as well as the Akjai. The Oankali-only group becomes their mediator, and ultimately creates a human-only colony in Mars. In Imago, the Oankali create a third species more powerful than themselves: the shape-shifting healer Jodahs, a human-Oankali ooloi who must find suitable human male and female mates to survive its metamorphosis and finds them in the most unexpected of places, in a village of renegade humans.