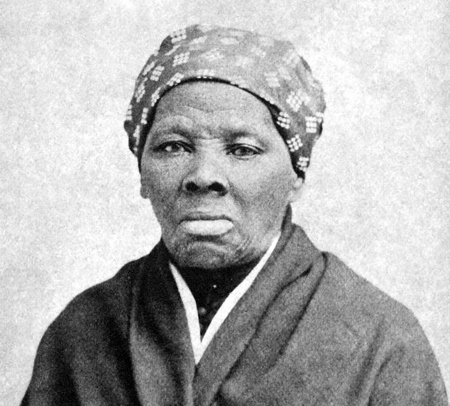

In 1862, Governor Andrew of Massachusetts arranged for Harriet Tubman to go to Beaufort, South Carolina, as a nurse and teacher to the Gullah people of the Sea Islands who had been left behind by their owners when they fled the advance of the Union Army, which remained in control of the islands.

Thomas B. Allen, author of “Harriet Tubman, Secret Agent,” writes that Tubman was approached by Gen. David Hunter to lead a raid. As Allen notes, generals don’t usually ask, they give orders. But Tubman was a woman and a civilian. Yes, she was spying and scouting for the Union army, but she was doing so outside the military chain of command.

Tubman agreed to the raid, but only if Col. James Montgomery – someone she knew well – would help her with it. National Geographic describes her as “the first woman in American history to lead a military expedition.”

Tubman and Montgomery took three gunboats up the Combahee River in South Carolina on the morning of June 1, 1863. The mission had multiple goals: Destroy bridges and attack the plantations along the river, and free the plantation slaves. “The raid was a key part of the Union plan to strike hard at the South’s rice crops, which provided food to the Confederates and wealth to South Carolina,” writes Mr. Allen.

Tubman’s crew consisted of former black slaves who had piloted riverboats (delivering cotton and other farm goods) and knew where the river had been mined. The raid was military success, and more than 700 slaves were freed. In fact, the gunboats were overwhelmed by slaves trying to clamor aboard what they called “Lincoln’s gun boats.”

Tubman believed that she was in the employ of the U.S. Army. When she received her first paycheck, she spent it to build a place where freed black women could earn a living doing laundry for the soldiers. But then she wasn’t paid regularly again, and wasn’t given the military rations she believed she was entitled to.

She was paid only a total of $200 in three years of service. She supported herself and her work by selling baked goods and root beer which she made after she completed her regular work duties.

After the war was over, Tubman was never paid her back military pay. In addition, when she applied for a pension — with the support of Secretary of State William Seward, Colonel T. W. Higginson, and General Rufus — her application was denied. Harriet Tubman did eventually receive a pension — but as the widow of a soldier, her second husband.