Good Thursday Morning POU!

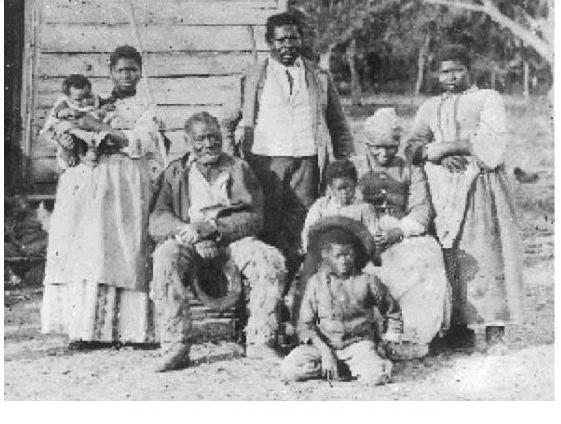

It is important to define “family” as it has been used by African Americans. Scholars generally agree that since the beginning of slavery in the United States, African Americans have viewed their families in terms of kin networks. These kin networks formed the social basis of African-American communities. Slaves were often forcefully removed from their families. They adapted to their circumstances by creating family units with other slaves with whom they lived and worked.

Slaves conferred the status of kin on non-blood relations, addressing each other as brother, sister, aunt, or uncle. Slave parents taught their children to address all older slave men and women by kin titles, a practice that bound them to these adults and prepared them in the event that sale or death separated them from their own parents and blood relatives. Parents relied on these kin networks to help them raise their children and understood that at any time, they may also need to assume the role of “aunt” or “uncle.” A black freedwoman remembered her uncle asking, “Should each man regard only his own children, and forget all the others?”

Slave owners regularly separated black family members from each other by sale. The “legacy of involuntary exodus was overwhelmingly destructive to their marriages, kin groups, and communities.” When the cotton and sugar plantations in the Lower South created a high demand for able-bodied slaves (especially men) in the nineteenth century, approximately one million black men, women, and children were sold from the Upper to the Lower South. The constant withdrawal of family members (especially men) from slave families damaged and sometimes destroyed slave marriages and families.

The antebellum South did not recognize slave families either by law or custom. Slaves could not legally marry, and slave parents had no legal claim to their children. Husbands and wives could only live together or visit each other with their masters’ consent. One great tragedy of the involuntary separation of parents and children was that many of the slave marriages endured long enough to produce children that had been nurtured by both of their parents before being sold away.

Maria Perkins, a slave, wrote her husband the following letter, which revealed her heartache at the forced breakup of her family:

Dear Husband I write you a letter to let you know my distress my master has sold albert to a trader on Monday court day and the other child is for sale also and I want you to let [me] hear from you very soon before next cort if you can I don’t know when I don’t want you to wait till Christmas I want you to tell dr Hamelton and your master if either will buy me they can attend to it know and then I can go afterwards I don’t want a trader to get me they asked me if I had got any person to buy me and I told them no they took me to the court house too they never put me up a man buy the name of brady bought albert and is gone I don’t know where they say he lives in Scottesville my things is in several places some is in staunton and if I should be sold I don’t know what will become of them I don’t expect to meet with the luck to get that way till I am quite heartsick Nothing more I am and ever will be your kind wife.

According to Brenda E. Stevenson, Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Los Angeles, this continual separation denied slaves the ability to function as families. It prevented them from sharing the responsibilities of households and children and providing each other with intimacy and love. No slave was immune to the danger of family separation. Since no one could predict when an owner would die and how his estate would be divided, all slave marriages were insecure. Statistics confirm this reality. In 1864–1865, one in four marriages of African Americans involved at least one member who had been forcefully separated from a spouse from an earlier marriage.

After Emancipation, one problem with reuniting families occurred when freedmen and freedwomen located their spouses only to find that they had remarried since their separation. Freedmen’s Bureau agents devised a tactic for resolving such problems.

One agent explained, “Whenever a negro appears before me with 2 or 3 wives who have equal claim upon him, I marry him to the woman who has the greatest number of helpless children who otherwise would become a charge on the bureau.” Typically, the woman that was selected was younger, since Bureau agents supposed that middleaged women would have older children that could support them.

Only about 4 percent of husbands abandoned one family to live with another. Some husbands and wives even lived in combined families with two or more wives per husband. Creative solutions such as this provide evidence of the commitment blacks felt towards their families, even amidst the challenges their families faced because of slavery. The task of reuniting families was often extremely difficult—if not impossible. Some slaves had been sold so often or so long before emancipation that family members no longer had reliable information about their whereabouts. For example, when Milly Johnson, a freedwoman in North Carolina, set out to locate her five children, she could only provide the Freedmen’s Bureau with reliable information about the whereabouts of one of them.

Reprinted from: The Effects of Slavery and Emancipation on African-American Families and Family History Research