Payne married in 1847, but his wife died during the first year of marriage from complications of childbirth. In 1854, he married again, to Eliza Clark of Cincinnati.

By 1840, Payne started another school. He joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in 1842. He agreed with the founder, Richard Allen, that a visible and independent black denomination was a strong argument against slavery and racism. Payne always worked to improve the position of blacks within the United States; he opposed calls for their emigration to Liberia or other parts of Africa, as urged by the American Colonization Society and supported by some free blacks.

Payne worked to improve education for AME ministers, recommending a wide variety of classes, including grammar, geography, literature and other academic subjects, so they could effectively lead the people. In the ensuing decades’ debates about “order and emotionalism” in the African Methodist Church, he sided consistently with order.

The AME’s first task was “to improve the ministry; the second to improve the people”. At a denominational meeting in Baltimore in 1842, Payne recommended a full program of study for ministers, to include English grammar, geography, arithmetic, ancient history, modern history, ecclesiastical history, and theology. At the 1844 AME General Conference, he called for a “regular course of study for prospective ordinees”, in the belief they would lift up their parishioners. In 1845 Payne established a short-lived AME seminary and succeeded in gradually raising the educational preparation required for ministers.

Payne also directed reforms at the style of music, introducing trained choirs and instrumental music to church practice. He supported the requirement that ministers be literate. Payne continued throughout his career to building the institution of the church, establishing literary and historic societies and encouraging order. At times he came into conflict with those who wanted to ensure that ordinary people could advance in the church. Especially after expansion of the church in the South, where different styles of worship had prevailed, there were continuing tensions about the direction of the denomination.

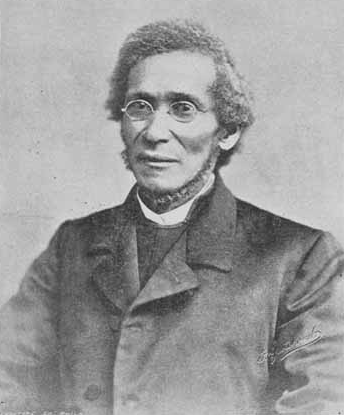

In 1848, Bishop William Paul Quinn named Payne as the historiographer of the AME Church. In 1852, Payne was elected and consecrated the sixth bishop of the AME denomination. He served in that position for the rest of his life.

Together with Lewis Woodson and two other African Americans representing the AME Church, and 18 European-American representatives of the Cincinnati Methodist Episcopal Conference, Payne served on the founding board of directors of Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856. Among the trustees who supported the abolitionist cause and African-American education was Salmon P. Chase, then governor of Ohio, who was appointed as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court by President Abraham Lincoln. The denominations jointly sponsored Wilberforce in 1856 to provide collegiate education to African Americans. It was the first historically black college in which African Americans were part of the founding.

Wilberforce was located at what had been a popular summer resort, called Tawawa Springs. It was patronized by people from Cincinnati, including abolitionists, as well as many white planters from the South, who often brought their mistresses of color and “natural” (illegitimate) multi-racial children with them for extended stays.

In one of the paradoxical results of slavery, by 1860 most of the college’s more than 200 paying students were mixed-race offspring of wealthy southern planters, who gave their children the education in Ohio which they could not get in the South. The men were examples of white fathers who did not abandon their mixed-race children, but passed on important social capital in the form of education; they and others also provided money, property, and apprenticeships.

With the Civil War, the planters withdrew their sons from the college, and the Cincinnati Methodist Conference felt it needed to use its resources to support efforts related to the war. The college had to close temporarily because of these financial difficulties. In 1863, Payne persuaded the AME Church to buy the debt and take over the college outright. Payne was selected as president, the first African-American college president in the United States. The AME had to reinvest in the college two years later when a southern sympathizer damaged buildings by fire. Payne helped organize fundraising and rebuilding. White sympathizers gave large donations, including $10,000 donations each from founding board member Salmon P. Chase and a supporter from Pittsburgh, as well as $4200 from a white woman. The US Congress passed a $25,000 grant for the college to aid in rebuilding. Payne led the college until 1877. Payne traveled twice to Europe, where he consulted with other Methodist clergy and studied their education programs.

In April 1865, after the Civil War, Payne returned to the South for the first time in 30 years. Knowing how to build an organization, he took nine missionaries and worked with others in Charleston to establish the AME denomination. He organized missionaries, committees, and teachers to bring the AME church to freedmen. A year later, the church had grown by 50,000 congregants in the South.

By the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877, AME congregations existed from Florida to Texas, and more than 250,000 new adherents had been brought into the church. While it had a northern center, the church was strongly influenced by its expansion in the South. The incorporation of many congregants with different practices and traditions of worship and music styles helped shape the national church. It began to reflect more of the African-American culture of the South.

In 1881, he founded the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, a club which invited speakers to present on topics relevant to African-American life and a part of the Lyceum movement. Payne died on November 2, 1893, having served the AME Church for more than 50 years.