Good Morning POU! Racists would rather their own children be denied an education rather than share resources with black people. SMDH.

On Sept. 12, 1958, Gov. Orval Faubus closed all Little Rock, Arkansas public high schools for one year rather than allow integration to continue, leaving 3,665 Black and white students without access to public education. During this year, ninety-three percent of white students and fifty percent of the Black students gained access to some form of alternative schooling.

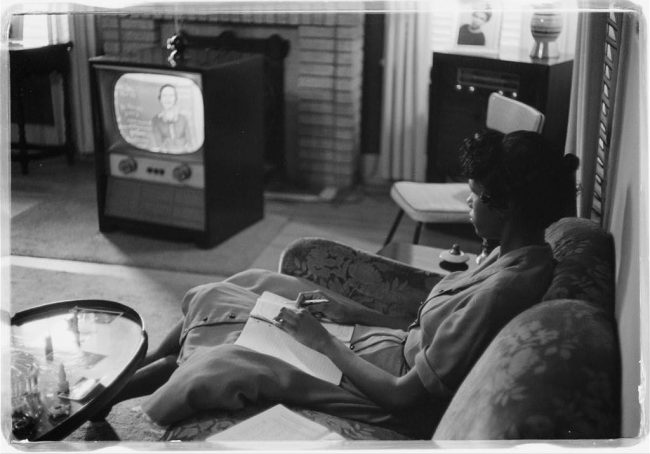

High school student taking a class via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration. By Thomas J. O’Halloran. Source: Library of Congress

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas explains,

Faubus’s action not only locked students from their classrooms but locked 177 teachers and administrators in the schools, where they had to fulfill their contractual obligations and appear for work, despite the empty classes.

The Lost Year was one of the most peculiar situations in Arkansas history. High school teachers worked in empty classrooms. A private school corporation formed to lease public school buildings and hire public school teachers, but federal courts prevented this. The school district experimented for a few weeks with television teaching by fifteen white teachers on the three commercial television stations. Soon, private schools, aside from the three Catholic parochial schools that already existed, opened to accommodate displaced white students. No private schools for black students emerged.

The Lost Year continued with its peculiarities. . . . The Arkansas General Assembly targeted the NAACP (Act 115) and public school teachers (Act 10) with threatening legislation. The latter required teachers and all public employees to sign affidavits listing all organizations to which they belonged and/or paid dues, while the former immediately fired any teacher or state employee who was a member of the NAACP. . . . Though no academic work was conducted in public high schools in 1958–59, high school football games continued for the season by order of the governor.

. . . Throughout the Lost Year, several groups organized either to support closed schools or to open them. Among those who worked tirelessly for the latter cause was a large group of white, upper-class women called the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open our Schools (WEC). They organized voter registration, promoted the election of moderates to the legislature and the school board, and worked with others after the teacher purge. The Capital Citizens Council (CCC) and the Mothers League of Central High supported segregation. The purge of forty-four teachers on May 5, 1959, brought voters from both sides of the spectrum to organize a recall of either segregationists or moderates from the Little Rock School Board. This twenty-day campaign was led by two hastily formed groups: the Committee to Retain Our Segregated Schools (CROSS) and a group called STOP (which stood for “Stop This Outrageous Purge”), which worked with the WEC. The Lost Year ended with a recall of three segregationist members of the Little Rock School Board on May 25, 1959. Voters in Little Rock, after a year of closed public high schools and after the firing of teachers, were finally willing to accept limited desegregation. Read in full.

The Lost Year Project

In the year following the Central High Crisis, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus signed into law legislation that would close all of the public high schools in Little Rock. More than 3,500 students—black and white—were locked out of public education, while almost 200 teachers and administrators were locked in under contract to serve empty classrooms.

Families were torn apart as teenage students moved away to attend schools in other towns or, in some cases, other states. Some studied to enter college early. Some took correspondence courses. Some simply abandoned school and went to work, or joined the military. Race was, predictably, a factor in the ways different students fared: 93 percent of white students found alternative schooling, while only 50 percent of black students were able to do the same.

The Lost Year was a time of great unrest for citizens of Little Rock. Families were in turmoil and communities were divided as the members of the School Board changed again and again, state legislators passed laws targeting members of the NAACP, and teachers were fired under suspicion of supporting integration.

The Little Rock Desegregation Crisis did not begin and end with Central High alone.

In the documentary film The Lost Year, the recollections of students and teachers who lived through this tumultuous time are interspersed with narration explaining the history and politics of the year to bring this previously untold story to vivid life.

The Lost Year is just one component of The Lost Year Project, which comprises a web site, the film, and a book. To learn more about the project, and about this fascinating and unexplored year in Arkansas history, visit The Lost Year Project.