We continue our look at black newspapers, magazines and other circulars published by and for African Americans in the 18th and early 19th century. Today’s entry is another great read that further puts to bed the notion that African Americans were idly waiting for white saviors in the fight against slavery.

Freedom’s Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States. Founded by Rev. Peter Williams, Jr. and other free black men in New York City, it was published weekly starting with the 16 March 1827 issue.

The newspaper was founded by Peter Williams, Jr. and other leading free blacks in New York City. The founders intended to appeal to the 300,000 free blacks in the North of the United States, most freed after the American Revolutionary War by state abolition laws. Manumissions (the act of a slave owner freeing his or her slaves) in the South after the war increased the proportion of free blacks from less than 1% to nearly 10% of the black population in the Upper South. In New York State, a gradual emancipation law was passed in 1799, granting freedom to children born to slaves. Its “gradual” provisions meant that the last slaves were not freed until 1827, the year the paper was founded.

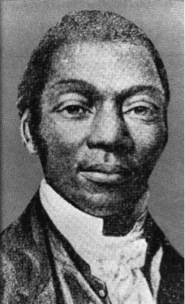

The newspaper founders selected Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm as senior and junior editors, respectively. Both men were community activists: Cornish was the first to establish an African-American Presbyterian church and Russwurm was a member of the Haytian Emigration Society. This group recruited and organized free blacks to emigrate to Haiti after its slaves achieved independence in 1804. It was the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first free republic governed by blacks.

According to the nineteenth-century African-American journalist, Irvine Garland Penn, Cornish and Russwurm’s objective with Freedom’s Journal was to oppose New York newspapers that attacked African Americans and encouraged slavery. For example, Mordecai Noah wrote articles that degraded African Americans; other editors also wrote articles that mocked blacks and supported slavery. The New York economy was strongly intertwined with the South and slavery; in 1822 half of its exports were cotton shipments. Its upstate textile mills processed southern cotton.

The abolitionist press had focused its attention on opposing the paternalistic defense of slavery and the Southern culture’s reliance on racist stereotypes. These typically portrayed slaves as children who needed the support of whites to survive or who were ignorant and happy as slaves. The stereotypes depicted blacks as inferior to whites and a threat to society if free.

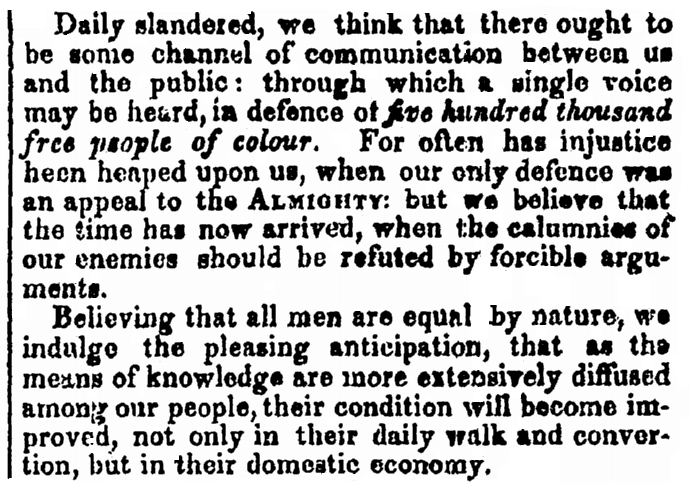

Cornish and Russwurm argued in their first issue: “Too long have others spoken for us, too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentations….” They wanted the newspaper to strengthen the autonomy and common identity of African Americans in society. “We deem it expedient to establish a paper,” buy viagra 50mg they remarked, “and bring into operation all the means with which out benevolent creator has endowed us, for the moral, religious, civil and literary improvement of our race….”

Freedom’s Journal provided international, national, and regional information on current events. Its editorials opposed slavery and other injustices. It also discussed current issues, such as the proposal by the American Colonization Society to resettle free blacks in Liberia, a colony established for that purpose in West Africa.

The Journal published biographies of prominent blacks, and listings of the births, deaths, and marriages in the African-American community in New York, helping celebrate their achievements. It circulated in 11 states, the District of Columbia, Haiti, Europe, and Canada.

The newspaper employed 14 to 44 subscription agents, such as David Walker, an abolitionist in Boston.

Freedom’s Journal was noted for publishing four articles known as Walker’s Appeal, by the abolitionist David Walker of Boston. He earlier published these articles as a pamphlet. Walker championed blacks caring for themselves and slaves initiating their own actions to end their condition. He wrote,

“…it is no more harm for you to kill the man who is trying to kill you than it is for you to take a drink of water…” – Walker’s Appeal

Walker also wrote against published assertions of black inferiority by the late President Thomas Jefferson, who died three years before Walker’s pamphlet was published. As he explained, “I say, that unless we refute Mr. Jefferson’s arguments respecting us, we will only establish them.”

He rejected the white assumption in the United States that dark skin was a sign of inferiority and lesser humanity. He challenged critics to show him “a page of history, either sacred or profane, on which a verse can be found, which maintains that the Egyptians heaped the insupportable insult upon the children of Israel, by telling them that they were not of the human family,” referring to the period when they were enslaved in Egypt.

Walker rejected the notion that the blacks should “sit idly by and wait for God to fight their battles — they must (and implicit in Walker’s language is the assumption that they will) take action and move to claim what is rightfully and morally theirs.”

“America,” Walker argued, “is more our country, than it is the whites — we have enriched it with our blood and tears.

In 1827, Cornish left the Freedom’s Journal and Russwurm began to promote colonization in Africa for American free blacks, as proposed by the American Colonization Society. His readers did not agree and abandoned the paper, which closed in 1829.

In 1829 Cornish tried to revive the African-American newspaper under the new title of “Rights of All,” the paper was short-lived and little is known about it.