Continuing on with the theme…

FACT 1:In 1787, free blacks in New York City found the African Free School, where future leaders Henry Highland Garnett and Alexander Crummell are educated.

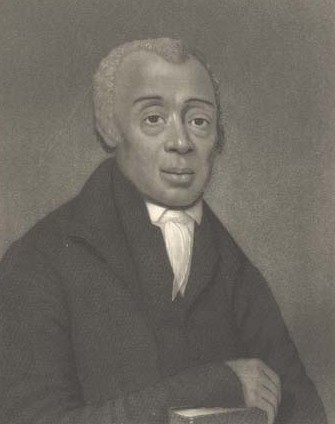

FACT 2: In 1787, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones form the Free African Society in Philadelphia.

FACT 3: In 1798, Joshua Johnston of Baltimore, Maryland becomes the first black portrait painter to gain widespread recognition in the United States.

According to Baltimore County court chattel records, Johnston was the son of a white man, George Johnston, and an unknown enslaved black woman owned by William Wheeler Sr., a small farmer. Wheeler sold Joshua Johnston to George Johnston in 1764 for 25 pounds, half the price of an adult male field slave. George Johnston arranged that Joshua would be freed after completing a blacksmith apprenticeship, or on turning 21, whichever came first; Joshua would go on to complete his apprenticeship with William Forepaugh, and was freed on July 15, 1782. Between 1796 and 1824, he was listed in most Baltimore City directories as a painter or limner. In the 1817-1818 directory he was also recorded as a “Free Householder of Color.”

Johnston was light-skinned and was easily mistaken for white, which may explain why some of his subjects at the time did not note his race. He advertised himself in the Baltimore Intelligencer as a “self-taught genius” who had “experienced many insuperable obstacles in the pursuit of his studies. There is no record of him being formally trained as an artist. He moved often within Baltimore, but as a free man was able to spend some time outside the city. For example, he is generally believed to have painted a portrait of Sarah Ogden Gustin in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia at some point between 1798 and 1802. Johnston may have supplemented his income by decorating furniture.

Of the thirteen existent paintings identified as his, many are of white children belonging to wealthy local families. He also painted black subjects, including Daniel Coker, a founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Johnston’s work is characterized by a rigidity of the arms and legs, indicative of the posed nature of his portraits. The works have a two dimensionality and the facial features are frequently vacant and staring. The backgrounds are notable for their detailed depictions of furniture or other props. Johnston’s work has often been associated with Baltimore artists Charles Willson Peale, Charles Peale Polk, and Rembrandt Peale and he was assumed to have been apprenticed to or enslaved by the family but there is no evidence of this connection. It is likely that the generic similarity to these artists is indicative of the type of American folk art created during that era. Joshua Johnston died in Baltimore in 1832.

FACT 4: In 1798, Venture Smith’s A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, A Native of Africa But Resident Above Sixty Years in the United States of America appears as the first slave narrative written by the person in bondage. Earlier narratives were written by white authors as dictated by enslaved people.

Venture Smith was a West African who was captured as a boy and sold into slavery in New England. He eventually purchased his own freedom, the freedom of several other slaves, and in his old age he wrote the earliest autobiography by an African American. His autobiography joined earlier slave narratives by British slaves that were published by abolitionists, and remains a testament to a remarkable life.

Smith’s autobiography is divided into three chapters. The first tells of his childhood in West Africa, his family and daily life, and then the invasion of slavers who tore him away from his home. The story of his capture includes the death of his father, who the slavers tortured to death in front of him, the march to the coast, and his sale to a New Englander, Robinson Mumford, for four gallons of rum and a piece of calico. Mumford renamed the boy “Venture,” to commemorate his personal investment in the slave trade.

In 1739, Venture and his new owner arrived in New England after traversing the Middle Passage. The second chapter covers his time in slavery, including his marriage to fellow slave Meg, his transfer between several owners and leasers, one aborted escape attempt, and his efforts to earn enough money to buy himself freedom. After almost five years of working odd jobs at night and in every spare moment, Venture Smith was able to save enough money to buy himself from his last master, Oliver Smith.

The third chapter of Smith’s autobiography narrates his life post-slavery. It is a story of much difficult work, mostly with the aim of purchasing his wife and children. Much of the story details jobs done, land bought and sold, contracts broken and hopes dashed. Life as an ex-slave wasn’t easy; Smith tells of the deaths of his oldest son and his daughter, and the several times he invested money only to be cheated without recourse to the law. However, he had some successes too, and in his old age Smith owned over 100 acres of land in Connecticut and three houses, and in spite of his blindness and poor health he described how happy he was that his wife, who he married for love and worked so hard to buy from slavery, was still alive.

Venture Smith’s autobiography was published in 1798, seven years before his death in 1805. In 2006 his descendants worked with the BBC and a team of archaeologists to exhume his grave and take DNA evidence from his remains in an effort to trace his ancestry in Africa and learn more about his early life and family. However, the results were inconclusive.

FACT 5: On August 30, 1800 Gabriel Prosser attempts a slave rebellion in Richmond, Virginia.

Born into slavery around 1775, Gabriel Prosser was owned by Thomas H. Prosser of Henrico County, Virginia. Little is known of Prosser’s life before the revolt that catapulted him into notoriety. Prosser’s two brothers, Solomon and Martin and his wife, Nanny, were all owned by Thomas Prosser and all participated in the insurrection.

Gabriel Prosser at the time of the insurrection was twenty-four years old, six feet two inches, literate, and a blacksmith by trade. He was described by a contemporary as “a fellow of courage and intellect above his rank in life.” With the help of other slaves including Jack Bowler and George Smith, Prosser devised a plan to seize control of Richmond by killing all of the whites (except the Methodists, Quakers and Frenchmen) and then establishing a Kingdom of Virginia with himself as monarch.

Prosser and the other revolt leaders were probably influenced by the American Revolution and more recently the French and Haitian Revolutions with their rhetoric of freedom, equality and brotherhood. In the months prior to the revolt Prosser recruited hundreds of supporters and organized them into military units. Although Virginia authorities never determined the extent of the revolt, they estimated that several thousand planned to participate including many who were to be armed with swords and pikes made from farm tools by slave blacksmiths.

Prosser planned to initiate the insurrection on the night of August 30, 1800. However, earlier in the day two slaves who wanted to protect their masters betrayed the plot to Virginia authorities. Governor James Monroe alerted the militia. A rainstorm delayed the uprising by 24 hours, preventing Prosser’s army from assembling outside Richmond and providing the militia crucial time to prepare a defense of the city. Realizing their plan had been discovered, Prosser and many of his followers dispersed into the countryside. About 35 leaders were captured and executed but Prosser escaped to Norfolk where he was betrayed by fellow slaves who claimed the reward for his capture on September 25. Prosser was returned to Richmond and tried for his role in the abortive uprising. He was found guilty on October 6, 1800 and executed the following day.

*** Information courtesy of Blackpast.org***