There were always two Harlems in the 1920s—the one that whites flocked to for pleasure and the one that (mostly) blacks lived and worked in. Guidebooks written for white readers presented Harlem as a “real kick,” “New York’s Playground,” a “place of exotic gaiety . . . the home-town of Jazz . . . a completely exotic world” where “Negroes . . . remind one of the great apes of Equatorial Africa.” Primitivists of many different stripes, from antiracists to racists and everything in between, held that white culture was dull, depleted, restricted, cold, without vibrancy or creativity, and that all the passion, purity, and pleasure it lacked was hidden away in black communities.

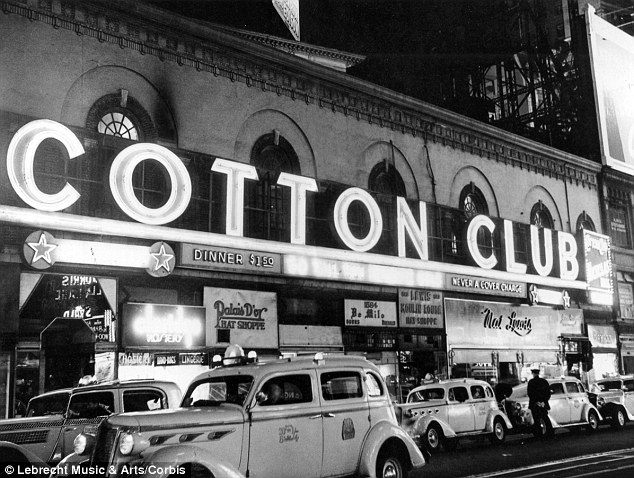

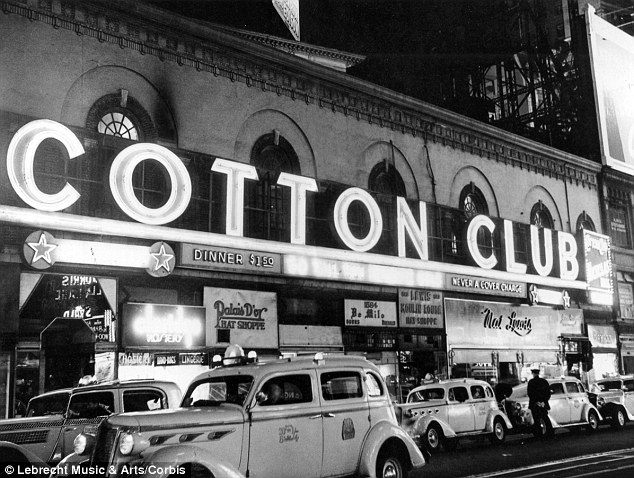

That conviction was the foundation of what Langston Hughes called the “Negro vogue,” making Harlem, in James Weldon Johnson’s words, “the great Mecca for the sight-seer, the pleasure-seeker, the curious, the adventurous” and drawing whites to shows at interracial cabarets or to clubs that catered to their patronage. Gay and straight, male and female, white would-be revelers descended on Harlem from taxis and subway stations, in spring weather and in snowstorms, individually and by guided tour, in hopes of an evening’s dose of the life-giving force they believed in and that popular culture reinforced. Harlem, Variety promised, “surpasses Broadway. . . . From midnight until after dawn it is a seething cauldron of Nubian mirth and hilarity. . . . The dancing is plenty hot. . . . The [Negro] folks up there . . . live all for today and know no tomorrow. . . . Downtown Likes Harlem’s Joints.” One travel writer gushed, “Here is the Montmartre of Manhattan . . . a great place, a real place, an honest place, and a place that no visitor should even think of missing. But visit Harlem at night; it sleeps by day!”

All the sudden popularity could be offensive. The idea that blacks should provide a social safety valve for stifled white passions was especially insulting, as was the pressure to perform a version of blackness that satisfied whites’ expectations. “Ordinary Negroes,” Langston Hughes maintained, did not “like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers—like amusing animals in a zoo.” One black newspaper called the influx of whites into Harlem “a most disgusting thing to see.” A 1926 article in the New York Age noted that “the majority of Harlem Negroes take exception to the emphasis laid upon the cabarets and night clubs as being representative of the real everyday life of that section. . . . All this has but little to do with the progress of the new Negro.” Wallace Thurman, usually known for irreverence, was uncharacteristically sober in objecting to the fact that “few white people ever see the whole of Harlem. . . . White people will assure you that they have seen and are authorities on Harlem and all things Harlemese.

That brings us to today’s Miss Anne – shipping heiress Nancy Cunard who once concluded that “I could speak as if I were a Negro myself.”

Her father was Sir Bache Cunard, an heir to the Cunard Line shipping businesses, interested in polo and fox hunting, and a baronet. Her mother was Maud Alice Burke, an American heiress, who adopted the first name Emerald and became a leading London society hostess. Nancy had been brought up on the family estate at Nevill Holt, Leicestershire but when her parents separated in 1911 she moved to London with her mother.

Cunard’s style was internationally known by her devotion to the artifacts of African culture, which at the time was startlingly unconventional. The large-scale jewelry she favored, crafted of wood, bone and ivory, the natural materials used by native crafts people, was considered provocative and controversial. The bangles she wore on both arms snaking from wrist to elbow were considered outré adornments, which provoked media attention, visually compelling subject matter for photographers of the day. She was often photographed wearing her collection, those of African inspiration and neckpieces of wooden cubes, which paid homage to the concepts of Cubism. At first considered the bohemian affectation of an eccentric heiress, the fashion world came to legitimize this style as avant-garde, dubbing it the “barbaric look.” Prestigious jewelry houses such as Boucheron created their own African-inspired cuff of gold beads. Boucheron, eschewing costly gemstones, incorporated into the finished creation green malachite and a striking purple mineral, purpurite, instead. It exhibited this high-end piece at the Exposition Coloniale in 1931.

In 1928 (after a two-year affair with French poet Louis Aragon) she began a relationship with Henry Crowder, an African-American jazz musician who was working in Paris. She became an activist in matters concerning racial politics and civil rights in the USA, and visited Harlem. In 1931 she published the pamphlet Black Man and White Ladyship, an attack on racist attitudes as exemplified by Cunard’s mother, whom she quoted as saying “Is it true that my daughter knows a Negro?” She also edited the massive Negro Anthology, collecting poetry, fiction, and nonfiction primarily by African-American writers, including Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. It also included writing by George Padmore and Cunard’s own account of the Scottsboro Boys case. Press attention to this project in May 1932, two years before it was published, led to Cunard’s receiving anonymous threats and hate mail, some of which she published in the book, expressing regret that “[others] are obscene, so this portion of American culture cannot be made public.” She identified as an anarchist (of course she did).

Nancy and Henry stayed together on and off until 1935, in spite of all their troubles. Her attitude toward monogamy humiliated him and left him bitter, although he had been married when they met and remained married throughout their affair. In later years he would claim that Nancy had taken advantage of her race and class privileges first to seduce him and subsequently to bully him into accepting their “peculiar association.” For her part, Nancy never had an unkind word to say about Crowder and always credited him with opening blackness for her. “Henry made me,” she said.

She had never believed that race was in the blood or biologically determined. She did not need to locate—or invent—remote black ancestors to claim a black identity. “As for wishing for some of it [blood] to be Coloured, no; that’s beyond me. That, somehow, I have NOT got in me—not the American part of it. But the AFRICAN part, ah, that is my ego, my soul.” Affiliation or affinity, not blood or lineage, Nancy felt, enabled her to “speak as if I were a Negro myself.” She was black, or partly black, she believed, because she felt herself to be so. What seemed so complicated to other people was, for Nancy, straightforward. “I like them [blacks] because I seem to understand them,” she declared. For those who truly care about others, Nancy wrote, “the tragedies of suffering humanity become as their own.” Feeling as strongly as she did about Africa meant, to Nancy, that she was part African and that giving expression to the realities of black life was her mission or calling. Volunteering for blackness seemed to her a necessary act, not an arrogant or appropriative one.

She was Rachel Dolezal before Rachel Dolezal.