By 1860, Smith was doing very well; he had moved to Leonard Street within the Fifth Ward and had a mansion built by white workmen. His total real property was worth $25,000. His household included a live-in servant, Catherine Grelis from Ireland.

After the 1863 draft riots, Smith and his family were among prominent blacks who left New York and moved to Brooklyn, then still a separate city. He no longer felt safe in his old neighborhood. In the 1870 census, Malvina and her four children were living in Ward 15, Brooklyn. All were listed as white. James W. Smith, who had married a white woman, was living in a separate household and working as a teacher; he was also classified as white. The Smith children still at home were Maud, 15; Donald, 12; John, 10; and Guy, 8; all were attending school.

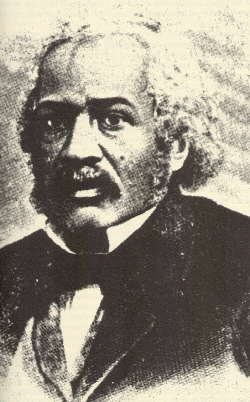

When he returned to New York City in 1837 with his degrees, Smith was greeted as a hero by the black community. He was the first university-trained African-American physician in the United States. During his practice of 25 years, he was also the first black to have articles published in American medical journals, but he was never admitted to the American Medical Association or local ones.

He established his practice in Lower Manhattan in general surgery and medicine, treating both black and white patients. He also started a school in the evenings, teaching children. He established what has been called the first black-owned and operated pharmacy in the United States, located at 93 West Broadway (near Foley Square today). His friends and activists gathered in the back room of the pharmacy to discuss issues related to their work in abolitionism.

In 1846, Smith was appointed as the only doctor of the Colored Orphan Asylum (also known as the Free Negro Orphan Asylum), at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue. He worked there for nearly 20 years. The asylum was founded in 1836 by Anna and Hannah Shotwell and Mary Murray, Quaker philanthropists in New York. Trying to protect the children, Smith regularly gave vaccinations for smallpox. Leading causes of death were infectious diseases: measles (for which there was no vaccine), smallpox and tuberculosis (for which there was no antibiotic at the time). In addition to caring for orphans, the home sometimes boarded children temporarily when their parents were unable to support them, as jobs were scarce for free blacks in New York.

Smith was always working for the asylum. In July 1852, he presented the trustees with 5,000 acres provided by his friend Gerrit Smith, a wealthy white abolitionist. The land was to be held in trust and later sold for benefit of the orphans.

In July 1863, during the three-day New York Draft Riots, in which most participants were ethnic Irish, rioters attacked and burned down the orphan asylum. The children were saved by the staff and Union troops in the city. During its nearly 30 years, the orphan asylum had admitted 1310 children, and typically had about 200 in residence at a time. After the riots, Smith moved his family and business out of Manhattan, as did other prominent blacks. Numerous buildings were destroyed in their old neighborhoods, and estimates were that 100 blacks were killed in the rioting. No longer feeling safe in the lower Fourth Ward, the Smiths moved to Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

While in Scotland, Smith joined the Glasgow Emancipation Society and met people in the Scottish and English abolitionist movement.In 1833 Great Britain abolished slavery. When Smith returned to New York, he quickly joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and worked for the cause in the United States.

During the mid-1850’s, Smith worked with Frederick Douglass to establish the National Council of Colored People, one of the first permanent black national organizations, beginning with a three-day convention in Rochester, New York. At the Convention in Rochester, he and Frederick Douglass emphasized the importance of education for their race and urged the founding of more schools for black youth. Smith wanted choices available for both industrial and classical education. Douglass valued his rational approach and said that Smith was “the single most important influence on his life.”

Opposing the emigration of American free blacks to other countries, Smith believed that native-born Americans had the right to live in the United States and a claim by their labor and birth to their land.

In 1840 he wrote the first case report by a black doctor, which his associate John Watson read at a meeting of the New York Medical and Surgical Society. (It acknowledged Smith was qualified, but would not admit him because of racial discrimination.) Soon after, Smith published an article in the New York Journal of Medicine, the first by a black doctor in the US. He drew from his medical training to discredit popular ideas about differences among the races. In 1843 he gave a lecture series, Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Races, to demonstrate the failings of phrenology, which was a so-called scientific practice of the time that was applied in a way to draw racist conclusions and attribute negative characteristics to ethnic Africans.

At Glasgow, Smith had been trained in the emerging science of statistics. He published numerous articles applying his statistical training. For example, he used statistics to refute the arguments of slave owners, who wrote that blacks were inferior and that slaves were better off than free blacks or white urban laborers. To do this, he drew up statistical tables of data from the census.

When John C. Calhoun, then US Secretary of State and former US Senator from South Carolina, claimed that freedom was bad for blacks, and that the 1840 U.S. Census showed that blacks in the North had high rates of insanity and mortality, Smith responded with a masterful paper. In “A Dissertation on the Influence of Climate on Longevity” (1846), published in Hunt’s Merchants’ Magazine, Smith analyzed the census both to refute Calhoun’s conclusions and to show the correct way to analyze data. He showed that blacks in the North lived longer than slaves, attended church more, and were achieving scholastically at a rate similar to whites.

In 1859 he published an article using scientific findings and analysis to refute the former president Thomas Jefferson’s theories of race, as expressed in his well-known Notes on the State of Virginia (1785).As early as 1859, Dr. McCune Smith said that race was not biological but was a social category. He also commented on the positive ways that ethnic Africans would influence US culture and society, in music, dance, food, and other elements. His collected essays, speeches and letters have been published as The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist.

In 1863 Smith was appointed as professor of anthropology at Wilberforce College, Ohio. It was founded in a collaboration between the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME Church) and the Methodist Church of Cincinnati as a college for students of color before the American Civil War. By 1860, it had numerous mixed-race students from the South, whose tuition was paid by their wealthy white planter fathers. The war caused the withdrawal of most southern students, threatening survival of the school. In 1863 the college was purchased by the AME Church and established as the first African American-owned and operated college in the United States.

At the time, Smith was too ill to take the position.He died two years later on November 17, 1865 of congestive heart failure on Long Island, New York at the age of 52. This was nineteen days before ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which abolished slavery throughout the country.

In 1870 the Smiths were again all classified as white on the census. James Smith Jr. had married a white woman and had children. His siblings also would marry white spouses and have families. Because of trying to escape racial prejudice, it appeared that they did not pass on the stories about their father’s achievements, as later generations did not learn of them. It was not until the twenty-first century that a connection was made again, and his descendants learned of some of their African-American ancestors.

***Information obtained from Wikipedia.org and About.com***