Good morning, POU! It’s Thursday, we are close to the weekend. Let’s continue with the theme…

African-American migration

Many blacks voted with their feet and left the South to seek better conditions. In 1879, Logan notes, “some 40,000 Negroes virtually stampeded from Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia for the Midwest.” More significantly, beginning about 1915, many blacks moved to Northern cities in the Great Migration. Through the 1930s, over 1.5 million blacks would leave the South for lives in the North, seeking work and the chance to escape lynchings and legal segregation. While they faced difficulties, overall they had better chances in the North.

They had to make great cultural changes, as most went from rural areas to major industrial cities, and had to adjust from being rural workers to being urban workers. As an example, in its years of expansion, the Pennsylvania Railroad recruited tens of thousands of workers from the South. In the South, alarmed whites, worried that their labor force was leaving, often tried to block black migration.

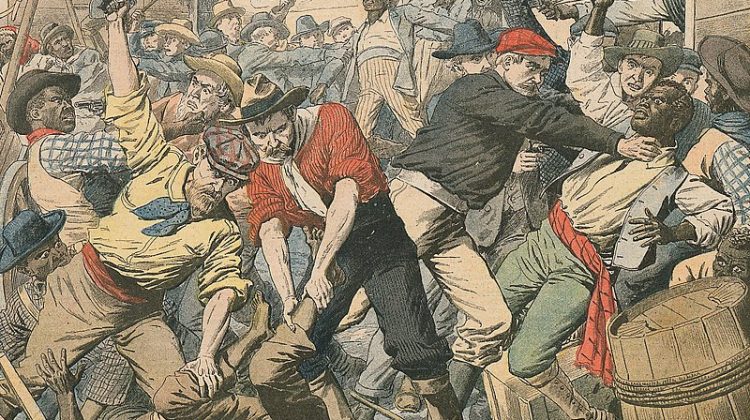

Northern hostility

During the nadir, Northern areas struggled with upheaval and hostility. In the Midwest and West, many towns posted “sundown” warnings, threatening to kill African Americans who remained overnight. These “Sundown” towns also expelled African-Americans who had settled in those towns during Reconstruction and before. They erected monuments to Confederate War dead across the nation–in Montana, for example.

Black housing was often segregated in the North. There was competition for jobs and housing as blacks entered cities which were also the destination of millions of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. As more blacks moved north, they encountered racism where they had to battle over territory, often against ethnic Irish, who were defending their power base. In some regions, blacks could not serve on juries.

Blackface shows, in which whites dressed as blacks portrayed African Americans as ignorant clowns, were popular in North and South. The Supreme Court reflected conservative tendencies and did not overrule Southern constitutional changes resulting in disfranchisement. In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that “separate but equal” facilities for blacks were constitutional; the Court was made up almost entirely of Northerners. However, equal facilities were rarely provided, as there was no state or federal legislation requiring them. It would not be until 58 years later, with Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that the Court recognized its 1896 error.

While there were critics in the scientific community such as Franz Boas, eugenics and scientific racism were promoted.