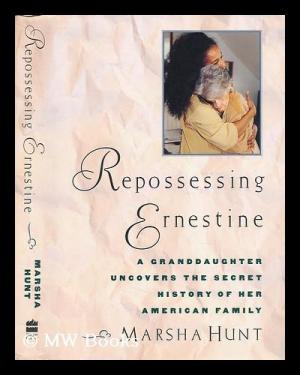

Welcome to Thursday POU! We continue to look at some other hidden figures in the past that might make for great viewing onscreen. An eclectic figure who comes from a “Our Kind Of People” family and is the inspiration for the Rolling Stones hit “Brown Sugar”……that is quite the combo huh? But it was Marsha Hunt’s book about finding her hidden grandmother that inspired today’s entry. This one is long, but a fascinating read which leaves lots of questions unanswered.

“That story is just tearing this town apart—just tearing us apart.” The others sitting around the table nodded in agreement as Erma Clanton pushed her shiny black hair from her left eye and gestured over to a large book that sat on my Aunt Earlene’s kitchen counter. “Dr. Hunt was a fine man, and it’s just a shame that he should be villified by his own flesh and blood,” added another woman who sat in the family room that opened up into the breakfast room where a dozen of us had collected the night before my uncle’s wake at the T. H. Hayes Funeral Home. Most of the fifteen or sixteen men and women who sat in the kitchen—including my parents—had grown up in Memphis. And they were fiercely protective of the highly esteemed black families who had played a role in the town’s history. The person they were talking about was Blair T. Hunt, leader of two of black Memphis’s most important black institutions: Booker T. Washington High School, the city’s first black high school, and Mississippi Boulevard Church.

“Those stories are just tearing us apart,” repeated Clanton, a recently retired professor who had taught drama for twenty years at Memphis State University. Like many on the South Side of Memphis, she was disturbed by a book that had recently been published by the granddaughter of Blair Hunt, the prominent educator and minister. “I don’t know how much we should believe anyway,” one of the men snapped.

“Isn’t she married to one of these white rock stars anyway?” My relatives shrugged as they listened to the well-substantiated rumor about how the beloved Hunt had allegedly placed his light-skinned wife in an insane asylum in the 1940s against her will. What was most shocking was that many of the old guard presumed that she had died in the 1950s, though when in fact she was still alive in the 1990s when her granddaughter wrote about her in the controversial book Repossessing Ernestine. – taken from Our Kind Of People by Lawrence Otis Graham.

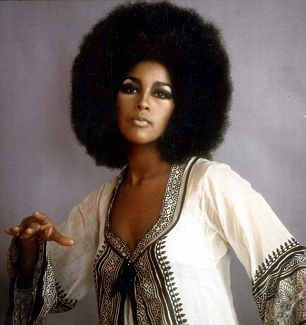

As it turns out, Marsha Hunt, actress, singer, model, muse of Mick Jagger, is the granddaughter of Blair T. Hunt, Jr. of the Memphis black elite history. But Marsha didn’t grow up in Memphis nor did she know anything about that side of her family until much later in life. Her father, Blaire Theodore Hunt was one of the first black psychiatrists in the country. She didn’t even know he committed suicide until she was 15 yrs old, and found out that it happened three years earlier.

Marsha’s Story

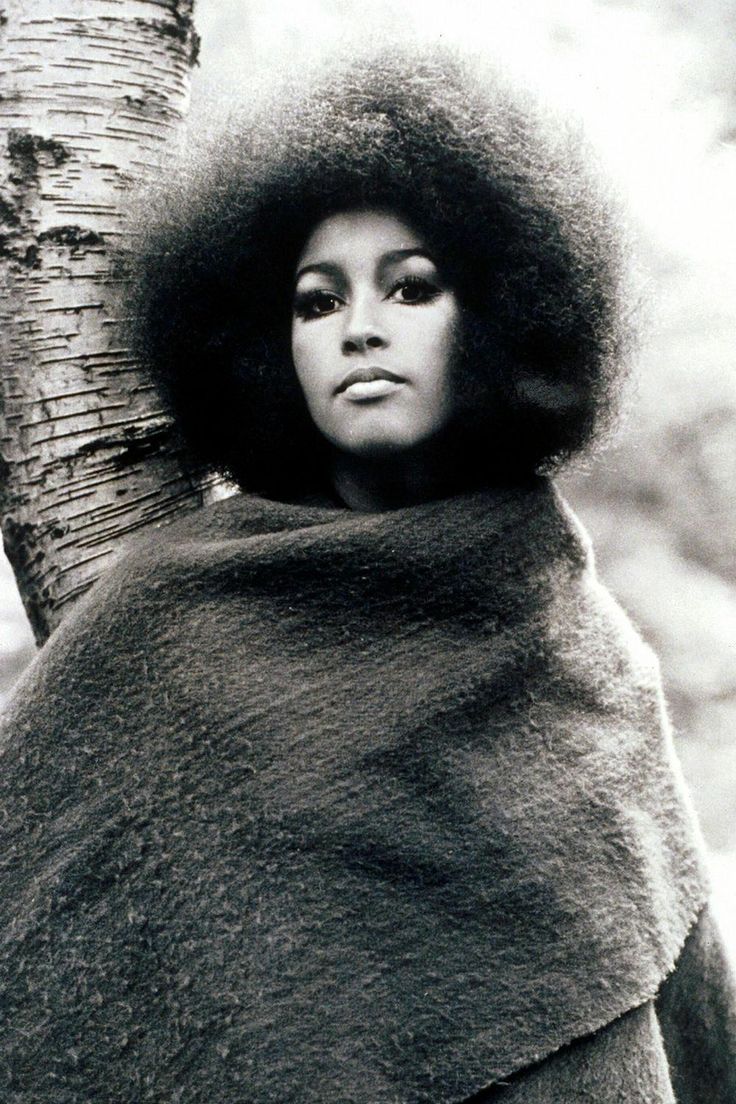

When Marsha Hunt wrote her autobiography, Real Life, in 1986, she didn’t know what to call herself. In Europe, where she’d lived half her life, she had found she was described solely as an American, not as a black or an African- one. It was only when she was back home, in the States, among her fellow countrymen, that her identity was split by that discriminating hyphen. “My skin color is oak with a hint of maple,” she writes. “Of the various races I know I comprise – African, American Indian, German Jew and Irish – only the African was acknowledged…I was labelled `colored’.”

Chafing against a definition that was skin-deep, she invented a word that she was comfortable with. “When I stumbled upon the French word melange, which means a mixture and also contains part of the word `melanin’, dark pigment found in the skin, it hit me like fireworks. Melange. I am a Melangian.” .

Now still, Marsha Hunt is searching for a way to define herself, and – this (the 90s) being the decade when family has become the neo-conservative successor to the selfish habits of Eighties me-isms – she has gone in search of her roots. She auditions in front of us for a role in her real family’s life.

Ernestine Martin was born on 15 August 1896, in an era when free blacks born in the American South were not issued with birth certificates which could document their ancestry or, for that matter, their existence. The first documentation of herself as a member of society fell to Ernestine in the US Census of 1906, where she is listed as a female mulatto. Although her mother’s name and profession are listed, no details are given of her father.

Growing up in Memphis, Tennessee, Ernestine was an intelligent, remarkably beautiful young woman who excelled in school and was greatly envied for her pale skin, blue eyes and blonde hair. Whether it was her intelligence or her beauty, or the combination, something about Ernestine captured the heart of one of her male teachers (and also the headmaster) – and to the surprise of her fellow students upon graduating from high school she married a man 20 years her senior: Blair T. Hunt Jr.

Blair Hunt, Marsha Hunt’s paternal grandfather, was and is an icon in Memphis’s black community. A son of slaves, a First World War veteran, he became Memphis’s leading public school administrator.

Although she is mentioned as the mother of Marsha’s own father, Blaire Theodore Hunt Jr, Ernestine’s name does not appear among the eight Hunts in the index to Real Life, because – following the birth of three sons in rapid succession after her marriage at the age of 17 – she was made to disappear.

When Marsha Hunt met her grandfather shortly before he died in 1978, he was living a sedately seedy life in Memphis with his female companion of 60-odd years, and spoke obliquely about his “poor dear sick wife” whom he had had to “put away” many years ago. Marsha’s own father had committed suicide, and her communication with his family was sporadic, at best. Ernestine she was told, had been sent to a state mental institution as a result of a violent psychosis – a hereditary illness, it was added – and, presumably, had died there.

It was Blair Hunt’s insistence that the illness was “hereditary” that put the sting on the tale for Marsha, especially after she became a mother, herself, in 1970. Visiting her father’s only surviving brother in Boston (another brother also committed suicide), Marsha couldn’t resist opening the closet that held the skeleton. And as a result of saying that she wished she knew more about her phantom grandmother, the phone rang one day in 1991, and her cousin told her: “I met someone who says he saw Ernestine.”

So begins the story of Marsha’s repossession of her grandmother’s dispossessed existence. “I was decades late,” she writes, when she finally tracks down Ernestine at the age of 95, in a Memphis nursing-home where there is no soap and no paper in the single toilet shared by the residents. The story of how Hunt propels herself on to her grandmother’s empty stage is one of almost superhuman persistence. Ernestine had had no contact with either family or friends for more than 60 years. “Her silence,” Hunt writes, “had a density, like the constant hum of a furnace, and settled on everything like a layer of dust… she’d forgotten that talking was part of being.”

All families have secrets but it’s hard to accept that sometimes we cannot know the truth. Marsha Hunt thought her grandmother, the subject of her book Repossessing Ernestine, had spent her life in a Tennessee mental institution from the time when her three sons were young children. Ernestine was said to have been retarded, to be delusional, to have turned violent, to be a vegetable; her mental instability was believed to be hereditary.

Learning that she could be alive, the author sets off on a quest to find her and to uncover the history of a family already bowed down by tragedy. Her father, the eldest son, killed himself at 37. Marsha felt he might have taken up psychiatry in the hope of helping to cure his mother, but her parents being divorced she knew little about him or his family. She discovers that he remarried and his second wife, Roberta, is one new acquaintance who proves to be supportive.

Ernestine received no visitors in 11 years at a Memphis nursing home, but her grand-daughter cannot bring herself to question her family’s reasons for neglect: Guilt? Shame? Fear? Equally, she cannot be deterred in her concern for her grandmother, her need to find out more.

Ernestine must have suffered in a place built for 1,000 patients which housed 2,400; all her teeth had been removed when she was only 30. The horror of it strikes home when Marsha realizes that one of her cousins, Will, a man in the prime of his life, has not yet lived as long as their grandmother spent in an institution: 52 years.

No bigger than a ten year old, Ernestine has withdrawn virtually to the point where she was ‘a deserted house’. She herself can provide no explanations. She says little, though in one poignant scene from the book, she recites the Twenty-third Psalm. Yet she insists she is a white girl, which is also on her admission records. Her generation took pride in being light-skinned, though it is an inescapable reminder of racial miscegenation and slavery; the author even wonders whether her grandmother might reject her because of her own darker skin. Seen as a black servant attending on a white woman rather than somebody looking after her beloved, frail grandmother, Marsha Hunt finds it hard to believe that white people will help her, or to trust what they tell her. ‘They used to do all kinds of things to women…lock [them] up just to stop them talking.’

What had happened to Ernestine, the girl whose old friends admired her, the brilliant and beautiful scholar, with her strangely blue eyes and blonde hair? And was this the reason headmaster Blair T Hunt married her, one of his own students? A highly regarded minister and member of the community, no criticism or comment seems to have been made about him.

Maybe Ernestine suffered postnatal depression – the children were raised in Boston by her mother, Mattie – or was she put away for other reasons? Her husband lived in Memphis for 47 years with his mistress, Harry Mae; divorce wasn’t recognized in Tennessee at the time and they could not marry while his wife was alive. After Blair T Hunt’s death, Harry Mae was responsible for paying his widow’s nursing home bills, but never once left her home to see for herself the conditions in which the other woman had to live. She claimed that as teenagers the boys had told their father they did not wish to visit Ernestine any more, and they did not think he should see her again either.

Though so much remains a mystery, one thing which shines through is Marsha’s love for her grandmother. She manages to bring Ernestine to England, but it proves impossible to give her the full-time care she needs.

Back in America, there’s some kind of happy ending, with a place for Ernestine in a comfortable nursing home near the family of her son Wilson and visits from her relatives, particularly the younger generation. And photographs, so evocative, show a seemingly spry old lady of 97. They also show Ernestine serious in her graduation robes, playful with her first baby.

Even if not wholly successful, Marsha Hunt never stopped trying to do what she felt was right: for her grandmother, for her father, for herself. By turn, heart-warming and heartrending, her determination is an inspiration.