GOOD MORNING P.O.U.!

THE ELAINE RACE RIOT

Philips County, Arkansas

The Elaine race riot, also called the Elaine massacre, began on September 30–October 1, 1919 at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. With an estimated 100 to 237 blacks killed, along with five white men, it is considered the deadliest race riot in the state and one of the deadliest racial conflicts in all of United States history.[4]Due to the widespread white mob attacks, in 2015 the Equal Justice Institute classified the black deaths as lynchings in their report on lynchings in the United States.[5]

Located in the Arkansas Delta, the county had been developed for cotton plantations, worked by African-American slaves. In the early 20th century the population was still overwhelmingly black: African Americans outnumbered whites in the area around Elaine by a ten-to-one ratio, and by three-to-one in the county overall.[4] Descendants of slaves, most blacks worked as sharecroppers. White landowners controlled the economic power, selling cotton on their own schedule, running high-priced plantation stores where farmers had to buy seed and supplies, and failing to itemize their settlement of accounts with sharecroppers.[4]

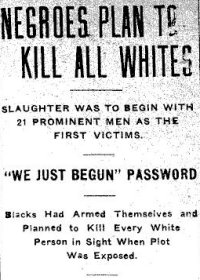

The Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America had organized chapters in the Elaine area in 1918-19. On September 29, representatives met with about 100 black farmers at a church near Elaine to discuss how to obtain fairer settlements. Whites resisted union organizing and often spied on or disrupted such meetings. In a confrontation at the church, two whites were shot, one fatally. The sheriff called a posse and whites gathered to put down a rumored “black insurrection”.[4] Other whites entered Phillips County to join the action, making a mob of 500 to 1000 whites. They attacked blacks on sight across the county. The governor called in 500 federal troops, who arrested nearly 260 blacks and were accused of killing some. Over a three-day period, five white men were killed and an estimated 100-240 blacks, with some estimates of more than 800 blacks killed. The events have been subject to debate, especially the total of black deaths.[4]

The only men prosecuted for these events were 122 African Americans, with 73 charged with murder. Twelve were quickly convicted and sentenced to death by all-white juries for murder of the white deputy at the church. Others were convicted of lesser charges and sentenced to prison. During appeals, the death penalty cases were separated. Six convictions (known as the Ware defendants) were overturned at the state level for technical trial details. These six defendants were retried in 1920 and convicted again, but on appeal the state supreme court overturned the verdicts, based on violations of the Due Process Clause and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, due to exclusion of blacks from the juries. The lower courts failed to retry the men within the two years required by Arkansas law, and the defense gained their release in 1923.[6]

The six other death penalty cases (known as Moore et al.) ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court overturned the convictions in the Moore v. Dempsey (1923) ruling. Grounds were the failure of the trial court to provide due process under the Fourteenth Amendment, as the trials had been dominated by adverse publicity and the presence of armed white mobs threatening the jury. This was a critical precedent for the “Supreme Court’s strengthening of the requirements the Due Process Clause imposes on the conduct of state criminal trials.”[6]

The NAACP assisted the defendants in the appeals process, raising money to hire a defense team, which it helped direct. When the cases were remanded to the state court, the six ‘Moore’ defendants settled with the lower court on lesser charges and were sentenced to time already served. Governor Thomas Chipman McRae freed these six men in 1925 in the closing days of his administration. The NAACP helped them leave the state safely.[6]

Background

With Phillips County developed for cotton plantations in the antebellum era, its population was overwhelmingly black and descended from slaves: in Phillips County, African-Americans outnumbered whites by a ten-to-one ratio. In the Arkansas Delta around the time of the Great War, most black farmers were sharecroppers and illiterate, as were many poor whites.

The Democratic-dominated legislature had disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites in the 1890s by creating barriers to voter registration. It excluded them from the political system via the more complicated Election Law of 1891 and a poll tax amendment passed in 1892. The white-dominated legislature enacted Jim Crow laws that established racial segregation and institutionalized Democratic efforts to impose white supremacy. The decades around the turn of the century were the period of the highest rate of lynchings across the South.

Sharecropping, the African Americans had been having trouble in getting settlements for the cotton they raised on land owned by whites. Both the Negroes and the white owners were to share the profits when the crop was sold for the year. Between the time of planting and selling, the sharecroppers took up food, clothing, and necessities at excessive prices from the plantation store owned by the planter.

— O.A. Rogers, Jr., President of the Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock, Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Summer 1960 issue

The landowner sold the crop whenever and however he saw fit. At the time of settlement, landowners generally never gave an itemized statement to the black sharecroppers of accounts owed, nor details of the money received for cotton and seed. The farmers were disadvantaged as many were illiterate. It was an unwritten law of the cotton country that the sharecroppers could not quit and leave a plantation until their debts were paid. The period of the year around accounts settlement was frequently the time of most lynchings of blacks throughout the South, especially if economic times were poor. Many Negroes in Phillips County whose cotton was sold in October 1918, did not get a settlement before July of the following year, and often amassed considerable debt at the plantation store before that time, as they had to buy supplies, including seed.

Black farmers began to organize in 1919 to try to negotiate better conditions, including fair accounting and timely payment of monies due them by white landowners. Robert L. Hill, a black farmer from Winchester, Arkansas, had founded the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America, and was working with farmers throughout Phillips County. Its purpose was “to obtain better payments for their cotton crops from the white plantation owners who dominated the area during the Jim Crow era. Black sharecroppers were often exploited in their efforts to collect payment for their cotton crops.”[4]

Whites tried to disrupt such organizing and threatened farmers.[6] The union had hired a white law firm in the capital of Little Rock to represent the black farmers in getting fair settlements for their 1919 cotton crops before they were taken away for sale. The firm was headed by Ulysses S. Bratton, a native of Searcy County and former assistant federal district attorney.[6]

The postwar summer of 1919 had already been marked by deadly race riots in more than three dozen cities across the country, including Chicago, Knoxville, Washington, DC, and Omaha, Nebraska. Competition for jobs and housing in crowded markets following World War I as veterans returned to society resulted in outbreaks of racial violence, usually of ethnic whites against blacks. Having served their country in the Great War, African-American veterans resisted racial discrimination and violence. In 1919 blacks vigorously fought back when their communities were attacked. Labor unrest and strikes took place in several cities as workers tried to organize. As industries hired blacks as strikebreakers in some cities, worker resentment against them increased.[4]