GOOD MORNING, P.O.U.!

Happy Birthday to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.!

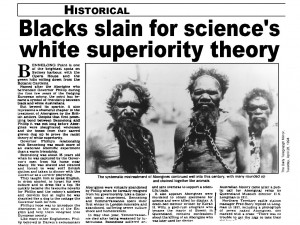

We continue our series on Racism In Australia with a look at how white scientists used Aboriginal people for the sole purpose of scientific experimentation.

A gruesome trade

The body parts of Australian Aboriginal folk were keenly sought after. Following Darwin and his contemporaries, they were regarded by scientists and other evolutionary enthusiasts as ‘living missing links’. The remains of some 10,000 dead Aboriginal people in all were shipped to British museums over the course of this frenzy to provide specimens for this ‘new science’.5

David Monaghan, an Australian journalist, extensively documented these—and far worse—effects of evolutionary belief. He spent 18 months researching his subject in London, culminating in an article in Australia’s Bulletin magazine6 and a TV documentary called Darwin’s Body-Snatchers. This aired in Britain on October 8, 1990.

Along with museum curators from around the world, Monaghan says, some of the top names in British science were involved in this large-scale grave-robbing trade. These included anatomist Sir Richard Owen, anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith, and Charles Darwin himself. Darwin wrote asking for Tasmanian skulls when only four full-blooded native Tasmanians were left alive. (Ever the Victorian gentleman, his request came with a caveat; provided, that is, that it would not upset their feelings.)

American evolutionists, too, were strongly involved in this flourishing ‘industry’ of gathering specimens of ‘sub-humans’, according to Monaghan. The Smithsonian Institution in Washington holds the remains of 15,000 individuals of various groups of people.

Museums were not only interested in bones, but in fresh skins as well. These would provide interesting evolutionary displays when stuffed. Pickled Aboriginal brains were also in demand, to try to demonstrate that they were inferior to those of whites.

Good prices were being offered for such specimens. Monaghan shows, on the basis of written evidence from the time, that there is little doubt that many of the ‘fresh’ specimens were obtained by simply going out and killing the Aboriginal people. The way in which the requests for specimens were announced was often a poorly disguised invitation to do just that. A death-bed memoir from Korah Wills, who became mayor of Bowen, Queensland, in 1866, graphically described how he killed and dismembered a local tribesman in 1865 to provide a scientific specimen.

Monaghan’s research indicated that Edward Ramsay, curator of the Australian Museum in Sydney for 20 years from 1874, was particularly heavily involved. He published a museum booklet which appeared to include his, my and your Aboriginal relatives under the designation of ‘Australian animals’. It also gave instructions not only on how to rob graves, but also on how to plug up bullet wounds in freshly killed ‘specimens’.

Many freelance collectors worked under Ramsay’s guidance. Four weeks after he had requested skulls of Bungee (Russell River) blacks, a keen young science student sent him two, announcing that they, the last of their tribe, had just been shot. In the 1880s, Monaghan writes, Ramsay complained that laws recently passed in Queensland to stop the slaughter of Aboriginals were affecting his supply.

The Angel of Black Death

According to Monaghan’s Bulletin article, that was the nickname given to a German evolutionist, Amalie Dietrich. She came to Australia asking station7 owners for their Aboriginal workers to be shot for specimens. She was particularly interested in skin for stuffing and mounting for her museum employers. Although evicted from at least one property, she shortly returned home with her specimens.

Monaghan also recounts how a New South Wales missionary was a horrified witness to the slaughter by mounted police of a group of dozens of Aboriginal men, women and children. Forty-five heads were then boiled down and the ten best skulls were packed off for overseas.

Still in recent times

As much as one would like to think that such attitudes are long gone, remnants still linger, including in the scientific community itself. This is shown by a telling extract from a secular writer in 2004 (emphasis added):

“It has been estimated that the remains of some 50,000 Aborigines are housed in medical and scientific institutions abroad. The Tasmanian Aboriginal remains in particular are there for two reasons. First, at the time of collection they were considered to be the most primitive link in the evolutionary chain, and therefore worthy of scientific consideration. Second, each skull fetched between five and ten shillings. … in anthropological terms, while the remains maintain currency as a museum item, the notion that they are a scientific curiosity remains. Put simply, if it is now accepted that Tasmanian Aborigines are not the weakest evolutionary link, that they are simply another group of people with attendant rights to dignity and respect, there is no longer any reason to keep their remains for study. Institutions should acknowledge that by returning the remains. There are two reasons why this is not as straightforward as it appears. First, the British Museum Act of 1962 did not allow British government institutions to deaccess stored material. Second, a number of scientists haven’t accepted that Tasmanian Aborigines are not on the bottom of Social Darwinist scales, and until they do, feet are being dragged.”8

Darwinist views about the racial inferiority of Aboriginal Australians drastically influenced their treatment in other ways too. These views were backed up by alleged biological evidences, which were only much later seen for what they were—distortions based on bias. In 1908 an inspector from the Department of Aborigines in the West Kimberley region wrote that he was glad to have received an order to transport all half-castes away from their tribe to the mission. He said it was “the duty of the State” to give these children (who, by their evolutionary reasoning, were going to be intellectually superior to full-blooded Aboriginal ones) a “chance to lead a better life than their mothers”. He wrote: “I would not hesitate for one moment to separate a half-caste from an Aboriginal mother, no matter how frantic her momentary grief”.9 Notice the use of the word ‘momentary’ to qualify ‘grief’; such lesser-evolved beings, sub-human as they were, were to him clearly not capable of feeling real grief.

Many genuine Australian Christians and church institutions, though patronizing on occasion, seem to have tried to protect Aboriginal people from the full brunt of the many inhumanities sanctioned by evolutionary thinking. However, like today, most church leaders and institutions compromised in some form or another with this new Darwinian ‘science’. Virtually no Christian voice in Australia did what was required—to affirm boldly the real history of mankind as given in the Bible. For the church to have stressed regarding Aboriginal people that we all go back only a few thousand years, to Noah’s family, would have helped strongly refute both pre-Darwinian racism and the maxi-spurt it received from Darwin. It would also have anticipated the findings of modern genetics, that biologically we are all extremely closely related.