The very name “Wall Street” is born of slavery, with enslaved Africans building a wall in 1653 to protect Dutch settlers from Indian raids. This walkway and wooden fence, made up of pointed logs and running river to river, later was known as Wall Street, the home of world finance. Enslaved and free Africans were largely responsible for the construction of the early city, first by clearing land, then by building a fort, mills, bridges, stone houses, the first city hall, the docks, the city prison, Dutch and English churches, the city hospital and Fraunces Tavern. At the corner of Wall Street and Broadway, they helped erect Trinity Church.

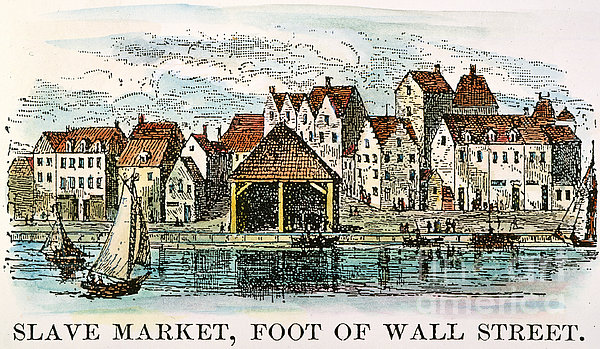

In 1711 the city’s Common Council established a Meal Market at Wall and Water streets for hiring slave labor and auctioning enslaved Africans who disembarked in Manhattan after their arduous trans-Atlantic journey. The merchants used these laborers to operate the port and in such trades as ship carpentry and printing, according to the National Park Service. Africans, according to the Park Service, also engaged in heavy transport, construction work, domestic labor, farming and milling. Their efforts were part of the euphemistically titled Triangular Trade: Africans living on what was then called the Gold Coast — with Africans being considered black gold — were bought using New England rum; the Africans were sold in the West Indies to work the fields to create sugar and molasses; and the sugarcane products were taken to New York and New England to be made into rum.

Pier 17 on the East River was a disembarkation point, as were all other slips and docks along lower Manhattan where the Hudson and East rivers rippled by. Today the pier is known as the South Street Seaport, a popular destination for gift-buying tourists who just happen to be visiting where enslaved Africans first touched land in chains.

The history of the area is described in Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited From Slavery — a book that details how deeply the slave trade was entrenched in America’s economy — by veteran newspaper journalists Anne Farrow, Joel Lang and Jenifer Frank. The authors wrote: “From 1825 on, in volume and value of imports and exports, the seaport of South Street outdid the combined trade of its two closest competitors in Boston and Philadelphia … long before civil war loomed, New York, after London and Paris, had become the third major city of the western world. Its glory was built largely of bricks of cotton,” the product of backbreaking labor.

“From seed to cloth, Northern merchants, shippers, and financial institutions, many based in New York, controlled nearly every aspect of cotton production and trade,” the authors continued. “Only large banks, generally located in Manhattan, or in London, could extend to plantation owners the credit they needed between planting and selling their crop … slaves were usually bought on credit.”

The Buttonwood Agreement, which started what became the New York Stock Exchange, was signed in 1792 under a buttonwood tree in front of 68 Wall Street, about a block away from the slave market at the intersection of Wall and Water streets. The agreement covered transactions and companies involved in the slave trade, including shipping, insurance and cotton.

Granted, many white folks did indeed help build America — as they profited from slavery. John Jacob Astor, who was born in Germany in 1763, became America’s first multimillionaire, making his fortune in furs, the China trade and cotton transportation, part of the slave trade. Astor, who died at age 84 in 1848, is the namesake of the Waldorf Astoria hotel and neighborhoods in New York City.

Moses Taylor, who helped finance the illegal slave trade, had his offices at 55 South Street, now part of the 111 Wall Street complex. His decades-long banking operations evolved into Citibank. He sat on the boards of firms that became Con Edison, Bethlehem Steel and AT&T, according to Alan J. Singer’s New York and Slavery: Time to Teach the Truth. When Taylor died in 1882, at age 76, his estate was worth $40 million to $50 million, or roughly $44 billion in current calculations.

There were also the three siblings — Henry Lehman and his two brothers, Mayer and Emanuel — who had emigrated from Germany to Alabama and, by 1850, formed Lehman Brothers, a merchandising business that quickly evolved into a cotton-brokerage firm. In 1870 the two surviving brothers moved to New York and helped establish the New York Cotton Exchange, the first commodities-futures trading venture. The company also helped found the Coffee Exchange and the Petroleum Exchange. (Their international investment firm died in 2008 as the great recession got under way.)

Another of the era’s top businessmen, Charles L. Tiffany, got the financing to open a fancy-goods store in 1837 at 259 Broadway from his father, who operated a cotton mill in eastern Connecticut using cotton picked by Southern slave labor. Thus, slave profits were instrumental in launching what became Tiffany & Co., the internationally renowned jeweler, whose current New York City offices are on Fifth Avenue and at 37 Wall Street.

In his book, Singer also explained: “The founders of Brown Bros. Harriman … built the bank by lending millions of dollars to Southern planters and arranging for the shipment and sale of slave-grown cotton in New England and Great Britain” during the 1800s. When the bank took control of three Louisiana plantations at one point, it also got 346 enslaved Africans.

And finally, after all that work, whites got to enjoy New York as the city played host to the 100,000 planters and their families who came north for cooler weather during the summer. Hotels, restaurants and entertainment venues geared up for their special visitors, offering Southern hospitality up north, as plantation owners rested from ordering about the people who were essential in creating America and its wealth.