Good Morning POU!

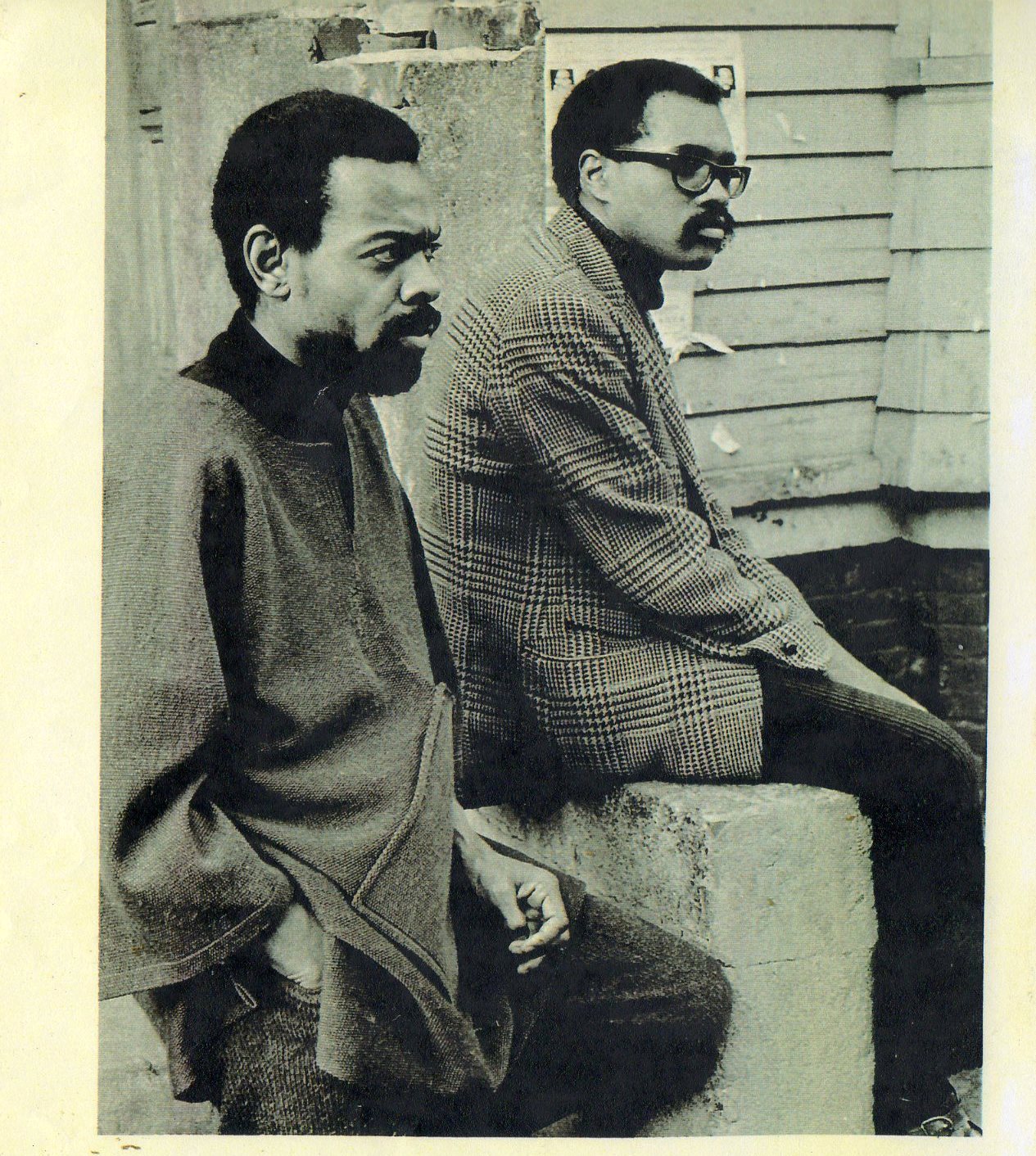

It was the Black Arts Movement that galvanized a generation of young black writers into rethinking the purpose of African American art. Rejecting any notion of the artist that separated him or her from the African American community, the Black Arts movement engaged in cultural nation building by sponsoring poetry readings, founding community theatres, creating literary magazines, and setting up small presses. In 1968 poetry, fiction, essays, and drama from writers associated with the movement appeared in the landmark anthology Black Fire, edited by Baraka and Larry Neal. One of the most versatile leaders of the Black Arts movement, Neal summed up its goals as the promotion of self-determination, solidarity, and nationhood among African Americans.

Amiri Baraka & Larry Neal, photo appears on back of their anthology Black Fire

To Black Arts writers, literature was frankly a means of exhortation, and poetry was the most immediate way to model and articulate the new Black consciousness the movement sought to foster. Larry Neal wrote the following:

The Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community. Black Art is the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept. As such, it envisions an art that speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America. In order to perform this task, the black Arts Movement proposes a radical reordering of the Western cultural aesthetic. It proposes a separate symbolism, mythology, critique, and iconology. The Black Arts and the Black Power concept both relate broadly to the Afro-American’s desire for self-determination and nationhood. Both concepts are nationalistic. One is politics; the other with the art of politics.

Recently, these two movements have begun to merge: the political values inherent in the Black Power concept are now finding concrete expression in the aesthetics of Afro-American dramatists, poets, choreographers, musicians, and novelists. A main tenet of Black Power is the necessity for Black people to define the world in their own terms. The Black artist has made the same point in the context of aesthetics. The two movements postulate that there are in fact and in spirit two Americas—one black, one white.

The Black artist takes this to mean that his primary duty is to speak to the spiritual and cultural needs of Black people. Therefore, the main thrust of this new breed of contemporary writers is to confront the contradictions arising out of the Black man’s experience in the racist West. Currently, these writers are re-evaluating Western aesthetic, the traditional role of the writer, and the social function of art. Implicit in this re-evaluation is the need to develop a “black aesthetic.”

It is the opinion of many Black writers, I among them, that the Western aesthetic has run its course: it is impossible to construct anything meaningful within its decaying structure. We advocate a cultural revolution in art and ideas. The cultural values inherent in Western history must either be radicalized or destroyed, and we will probably find that even radicalization is impossible. In fact, what is needed is a whole new system of ideas. Poet Don L. Lee expresses it:

We must destroy Faulkner, dick, jane, and other perpetrators of evil. It’s time for Du Bois, Nat turner, and Kwame Nkrumah. As Frantz Fanon points out: destroy the culture and you destroy the people. This must not happen. Black artists are culture stabilizers; bringing back old values, and introducing new ones. Black Art will talk to the people and with the will of the people stop impending “protective custody.”

The Black Arts Movement eschews “protest” literature. It speaks directly to Black people. Implicit in the concept of ‘protest” literature, as brother Knight has made clear, is an appeal to white morality:

Now any Black man who masters the technique of his particular art form, who adheres to the white aesthetic, and who directs his work toward a white audience is, in one sense, protesting. And implicit in the act of protest is the belief that a change will be forthcoming once the masters are aware of the protestor’s “grievance” (the very word connotes begging, supplications to the gods). Only when that belief has faded and protestings end, will Black art begin.

Baraka’s Black Magic (1969) and It’s Nation Time (1970) typify the stylistic emphases of the poetry of this movement, particularly its preference for street slang, the rhythm of blues, jazz, and gospel music, and a deliberately provocative confrontational rhetoric. Important poets in this mode were Sonia Sanchez, Jayne Cortez, Etheridge Knight, Haki R. Madhubuti, Carolyn M. Rodgers, and Nikki Giovanni.

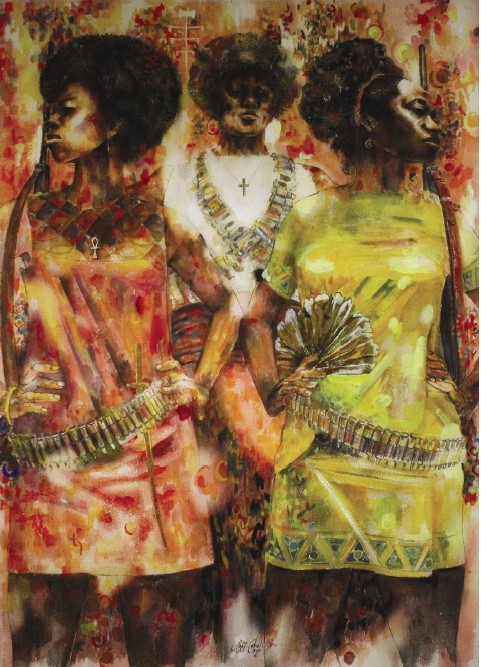

Rather than creating artwork that would encourage white America to look upon African Americans more positively, BAM artists were exclusively interested in improving black Americans’ perception of themselves. The call for Black Power, first issued as a challenge and later as a rejection of integrationist aims, arose with the belief that African Americans and black peoples living abroad would never be liberated from a racist society if they did not address internalized assumptions of inferiority. Advancing African American liberation through self-determination and, in time, Black Nationalism, the “Black Power Concept” directed African Americans to separate from mainstream (understood as white) society to determine “who are black people, what are black people, and what is their relationship to America and the rest of the world.”

To address these questions, BAM cultural theorists and artists reasoned that a black aesthetic–a distinguishing mark of black culture–was required to help the African American community perceive itself as Black–an appellate that, by the 1960s, would mean not only beautiful, but also pride in the legacy of African American achievement, self-identification with black peoples spread throughout the African diaspora, and an active participation in the sociopolitical uplifting of the black community. Defining “Black” art exclusively as cultural productions that facilitated the Black Power “revolution” in African American self-perception, BAM theorists and adherents directed African American artists to work collectively to develop a black aesthetic for each field of art. Whether the daring juxtapositions of jazz or the biting rhythms of poetry, this black aesthetic was intended to advance the liberation of African American self-perception–black peoples seeing themselves and their world “in terms of their own realities.”