It is impossible to engage in a complete discussion of the Harlem Renaissance without acknowledging the financial and tangible contributions of white patrons and their support of black intellectuals. White patronage had a profound effect on the vitality of the Harlem Renaissance, and evidence suggests that the Renaissance would not have reached the heights that it did without generous white contributions. White money and white connections were crucial catalysts for the movement in its early years. While their intentions were considered to be good, white support still elicited mixed feelings among the Harlem community, as some defined their participation in the movement as a sort of “refined racism”.

This New Negro movement soon became a form of entertainment for whites. White downtowners would flock to Harlem to “experience the primitive without having to go to Africa”. The influx of whites brought the Jim Crow mentality to Harlem, and soon popular cabarets and nightclubs were turning away black clientele. This segregation made sense considering that whites mostly owned the clubs. What took place was essentially a white capitalization and exploitation of African-American success. Oftentimes, the only blacks to be seen in clubs were the servers and entertainers. This dichotomy was not lost on the black intellectuals of the era.

All the sudden popularity could be offensive. The idea that blacks should provide a social safety valve for stifled white passions was especially insulting, as was the pressure to perform a version of blackness that satisfied whites’ expectations. “Ordinary Negroes,” Langston Hughes maintained, did not “like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers—like amusing animals in a zoo.”

One black newspaper called the influx of whites into Harlem “a most disgusting thing to see.” A 1926 article in the New York Age noted that “the majority of Harlem Negroes take exception to the emphasis laid upon the cabarets and night clubs as being representative of the real everyday life of that section. . . . All this has but little to do with the progress of the new Negro.” Wallace Thurman, usually known for irreverence, was uncharacteristically sober in objecting to the fact that “few white people ever see the whole of Harlem. . . . White people will assure you that they have seen and are authorities on Harlem and things Harlemese. When pressed for amplification they go into ecstasies over the husky-voiced blues singers, the dancing waiters, and Negro frequenters of cabarets who might well have stepped out of a caricature.”

Others, however, while agreeing that the “vogue” was suspect and sure to be short-lived, advocated taking advantage of the sudden surge of interest as long as it lasted. Black novelist Nella Larsen urged her friends to “write some poetry, or something” quickly, before the fad ended. Zora Neale Hurston took white friends to hear jazz and see black church services. It never occurred to her to charge for doing this. Enterprising black tour guides, on the other hand, charged $5 a person for “slumming” parties of the Harlem cabarets. One “slumming hostess” mailed prospective white clients an invitation that read:

Here in the world’s greatest city it would both amuse and also interest you to see the real inside of the New Negro Race of Harlem. You have heard it discussed, but there are very few who really know. Because the new Negro will be looked upon as a novelty, I am in a position to carry you through Harlem as you would go slumming through Chinatown. My guides are honest and have been instructed to give the best of service, and I can give the best of references of being both capable and honest so as to give you a night or day of pleasure. Your season is not completed with thrills until you have visited Harlem through Miss _________________’s representatives.

How To Play The Game: Niggerati Networking the Negrotarians

Carl Van Vechten and his wife, Fania Marinoff, would throw spectacular parties in their apartment on West 55th Street (sometimes referred to as the “Midtown office of the N.A.A.C.P.”). According to Langston Hughes, they were parties “ so Negro that they were reported as a matter of course in the colored society columns, just as though they occurred in Harlem.” Careers could be created from the networking opportunities such parties provided. Van Vechten’s daily notebooks detail that.

Nella Larsen wanted to write her way into the “vogue” in 1927 but had no background as a writer. She wrote a short, intense novella about the myriad obstacles to a young black woman’s fulfillment. Without Harlem’s social whirl, it would have stalled. The “Negrotarian” parties were her opportunity.

On March 16, 1927, she went to a party at the Van Vechten–Marinoffs’ at which she mingled with Nickolas Muray, the era’s most important photographer; Louise Bryant, a New Woman activist and the wife of John Reed; Harlem celebrity James Weldon Johnson; William Rose Benét, the publisher of The Saturday Review of Literature; his wife, writer Elinor Wylie; and editor and publisher Blanche Knopf. Four nights later, she joined Van Vechten and Marinoff for another party, that time at the home of actress Rita Romilly, where she spent the evening with Harry Block, a senior editor at Knopf; T. R. Smith, the senior editor at Boni & Liveright (then the second most important publisher of black literature); and Blanche Knopf again.

Nine days later, she joined some of the same group at a party that also included Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Walter White, Rebecca West, French writer Paul Morand, and others. White editors such as Blanche Knopf were anxious for black manuscripts but also insecure about their ability to judge black literature. They leaned heavily on the advice of a few white advisers and favored black writers recommended by them, especially those they had come to know socially.

That month, Knopf accepted Larsen’s first novel, Quicksand. While it was being edited at Knopf, Larsen attended another party, on April 6, that included A’Lelia Walker; Paul Robeson; Walter White; Geraldyn Dismond; and the editor of the Chicago Defender , one of the most important black newspapers in the country. A few nights after that, she attended another small party with Van Vechten and Marinoff, Langston Hughes, and Dorothy Peterson, a poet and writer. Over the next few nights she attended parties given by Dorothy Peterson and by Eddie Wasserman, the heir to the Seligman banking fortune; these parties included such guests as Harlem Renaissance writer and gadfly Richard Bruce Nugent, poet Georgia Douglas Johnson, writer Alice Dunbar-Nelson, writer and editor Arna Bontemps, salonista and writer Muriel Draper, and, again, editor Blanche Knopf.

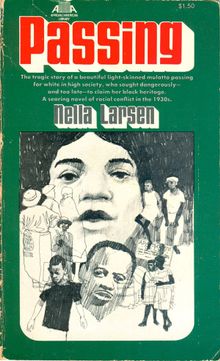

In March 1928, Larsen won second place in the coveted Harmon Award for literature. In the fall of 1929, her second novel, Passing , was accepted by Knopf. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Passing was feted with a “tea” (cocktail party) at Blanche Knopf’s on the day of its publication, ensuring that it received widespread critical attention and good initial sales.