Good morning, POU! This week’s threads focus on the relationship between the Black and Jewish communities.

Murder of Jewish civil rights activists

The summer of 1964 was designated the Freedom Summer, and many Jews from the North and West traveled to the South to participate in a concentrated voter registration effort. Two Jewish activists, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and one black activist, James Chaney, were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan near Philadelphia, Mississippi, because of their participation. Their deaths were considered martyrdom by some and temporarily strengthened black-Jewish relations.

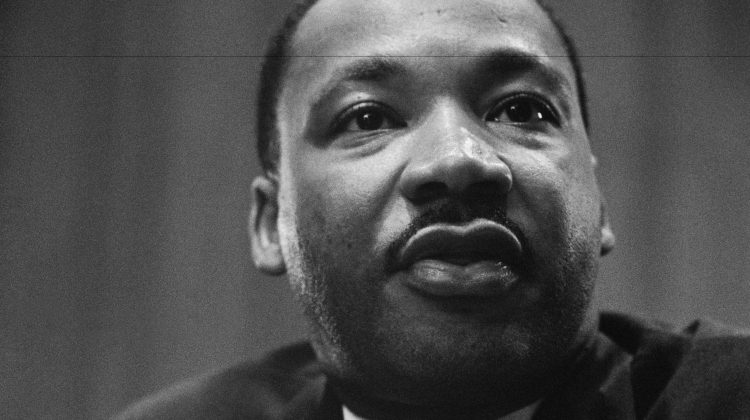

Martin Luther King, Jr., said in 1965,

How could there be anti-Semitism among Negroes when our Jewish friends have demonstrated their commitment to the principle of tolerance and brotherhood not only in the form of sizable contributions, but in many other tangible ways, and often at great personal sacrifice. Can we ever express our appreciation to the rabbis who chose to give moral witness with us in St. Augustine during our recent protest against segregation in that unhappy city? Need I remind anyone of the awful beating suffered by Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld of Cleveland when he joined the civil rights workers there in Hattiesburg, Mississippi? And who can ever forget the sacrifice of two Jewish lives, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, in the swamps of Mississippi? It would be impossible to record the contribution that the Jewish people have made toward the Negro’s struggle for freedom—it has been so great.

Questioning the “golden age”

Some recent scholarship suggests that the “golden age” (1955–1966) of the black–Jewish relationship was not as ideal as it is often portrayed.

Philosopher and activist Cornel West asserts that there was no golden age in which “blacks and Jews were free of tension and friction”. West says that this period of black–Jewish cooperation is often downplayed by blacks and romanticized by Jews: “It is downplayed by blacks because they focus on the astonishingly rapid entry of most Jews into the middle and upper middle classes during this brief period—an entry that has spawned… resentment from a quickly growing black impoverished class. Jews romanticize this period because their present status as upper middle dogs and some top dogs in American society unsettles their historic self-image as progressives with a compassion for the underdog.”

Historian Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz points out that the number of non-Southern Jews that went to the southern states numbered only a few hundred, and that the “relationship was frequently out of touch, periodically at odds, with both sides failing to understand each other’s point of view.”

Political scientist Andrew Hacker wrote: “It is more than a little revealing that whites who travelled south in 1964 referred to their sojourn as their ‘Mississippi summer’. It is as if all the efforts of the local blacks for voter registration and the desegregation of public facilities had not even existed until white help arrived… This was done with benign intentions, as if to say ‘we have come in answer to your calls for assistance’. The problem was… the condescending tone… For Jewish liberals, the great memory of that summer has been the deaths of Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner and—almost as an afterthought—James Chaney. Chaney’s name is listed last, as if the life he lost was worth only three fifths of the others.”

Southern Jews in the civil rights movement

Jews undertook the vast majority of civil rights activism by American Jews from the northern and western states. Jews from the southern states engaged in virtually no organized activity on behalf of civil rights. This lack of participation was puzzling to some northern Jews, because of the “inability of the northern Jewish leaders to see that Jews, before the battle for desegregation, were not victims in the South and that the racial caste system in the south situated Jews favorably in the Southern mind, or ‘whitened’ them.” However, there were some southern Jews who participated in civil rights activity as individuals.

Rabbi Jacob Rothschild was the rabbi of Atlanta’s oldest and most prominent Jewish synagogue, The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, also known as “the Temple”, from 1946 until his death in 1973, where he distinguished himself as an outspoken proponent for civil rights. Upon arriving in Atlanta (after living most of his life in Pittsburgh), the depth of racial injustice disturbed Rabbi Rothschild he witnessed and resolved to make civil rights a focal point of his rabbinical career. He first broached the topic in his 1947 Rosh Hashanah sermon but remained mindful of his status as an outsider and proceeded with some caution to avoid alienating supporters during his first few years in Atlanta. By 1954, however, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Brown v. Board of Education decision, which called for the desegregation of public schools, race relations had become a recurring theme in his sermons, and Temple members had grown accustomed to his support of civil rights.

He reached out to members of the local Christian clergy and became active in civic affairs, joining the Atlanta Council on Human Relations, the Georgia Council of Human Relations, the Southern Regional Council, the Urban League, and the National Conference of Christians and Jews. To promote cooperation with his Christian colleagues, Rothschild established the Institute for the Christian Clergy, an annual daylong event hosted by the Temple each February. Black ministers were always welcome at the Temple’s interfaith events, and on other occasions Rothschild invited prominent black leaders, such as Morehouse College president Benjamin Mays, to lead educational luncheons at the Temple, despite objections from some members of his congregation.

In 1957, when other southern cities were erupting in violent opposition to court-ordered school desegregation, eighty Atlanta ministers issued a statement calling for interracial negotiation, obedience to the law, and a peaceful resolution to the integration disputes that threatened Atlanta’s moderate reputation.[citation needed] The Ministers’ Manifesto, as the statement came to be known, marked an important turning point in Atlanta’s race relations. Although the Manifesto’s strong Christian language prevented Rothschild from signing it himself, the rabbi helped to draft and conceive the statement, and he endorsed it in an article that ran separately in both the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution and later appeared in the Congressional Record.

While Rothschild’s activism won admiration from some quarters of the city, it earned contempt from others. When fifty sticks of dynamite exploded at the Temple on October 12, 1958, many observers concluded that the rabbi’s outspoken support of civil rights had made the synagogue a target for extremist violence. Because elected officials condemned it, members of the press, and the vast majority of ordinary citizens, however, the bombing resulted in a repudiation of extremism and a renewed commitment to racial moderation by members of official Atlanta.

Rather than withdraw from public life, Rothschild stepped up his activism following the bombing, speaking regularly to support civil rights at public events throughout the city and region, and assuming the vice presidency of the Atlanta Council on Human Relations. Members of his congregation followed Rothschild’s lead, taking leadership positions in HOPE (Help Our Public Education) and OASIS (Organizations Assisting Schools in September), two influential organizations that helped ensure the peaceful integration of Atlanta’s public schools in 1961.

During this period, Rothschild forged a close friendship with Martin Luther King Jr. After King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, Rothschild helped to organize a city-sponsored banquet in King’s honor, for which also he served as master of ceremonies. Following King’s assassination in 1968, the combined clergy of Atlanta held a memorial service at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. Philip to pay their respects, and his peers selected Rothschild to deliver the eulogy.

In the years after King’s death, Rothschild’s opposition to the more militant measures adopted by younger black activists cost him much of the support he once enjoyed from his African American counterparts in the civil rights movement. His diminished stature in the black community notwithstanding, Rothschild continued to speak regularly and candidly about social justice and civil rights until he died, after suffering a heart attack, on December 31, 1973.

Recent decades have shown a greater trend for southern Jews to speak out on civil rights issues, as shown by the 1987 marches in Forsyth County, Georgia.