Good Morning POU!

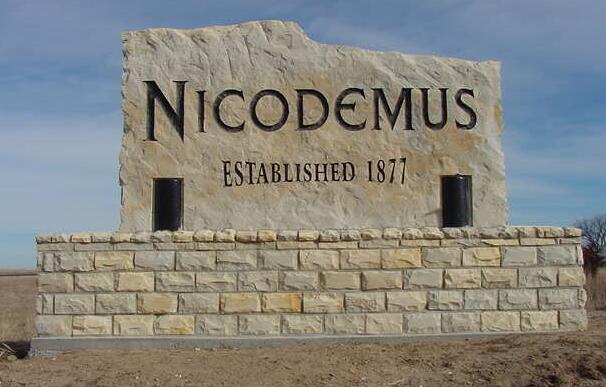

Nicodemus, Kansas the only remaining western community established by African Americans after the Civil War. Having an important role in American History, the town symbolizes the pioneering spirit of these ex-slaves who fled the war-torn South in search of “real” freedom and a chance to restart their lives. This “ghost town” has since gained recognition as a National Historic Site.

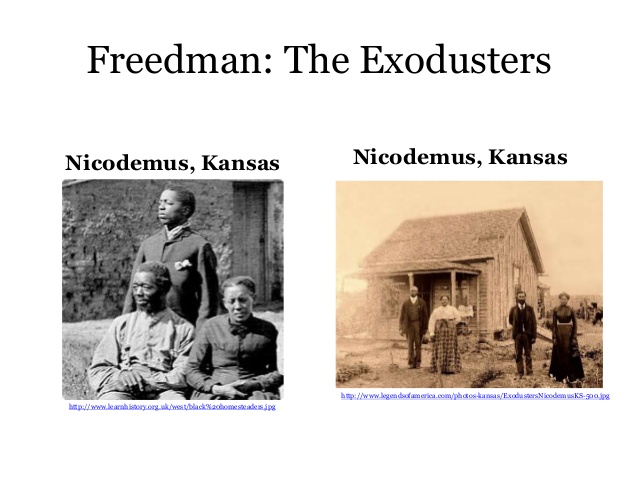

In the late 1870’s the black population of the South was extremely restless, as the Reconstruction following the Civil War failed to bring the long awaited freedom, equality and prosperity. Instead, they were racially oppressed, poverty-stricken, debt-ridden and starving.

At this time, along came a white man by the name of W.R. Hill, who described a “Promise Land” in Kansas to black families in the backwoods of Kentucky and Tennessee. Hill told of a sparsely settled territory with abundant wild game, wild horses that could be tamed, and an opportunity to own land through the homesteading process in Nicodemus, Kansas.

The town site of Nicodemus was planned in 1877 by W.R. Hill, a land developer from Indiana, and Reverend W.H. Smith, a black man, forming the Nicodemus Town Company. Reverend Smith became the President of the Town Company and Hill, the treasurer. Named for a legendary figure that came to America on a slave ship and later purchased his freedom, the two founders aggressively promoted the town to the black refugees of the Deep South. The Reverend Simon P. Roundtree was the first settler, arriving on June 18, 1877. Zack T. Fletcher and his wife, Jenny Smith Fletcher (the daughter of Reverend W.H. Smith) arrived in July and Fletcher was named the secretary of the Town Company. Smith, Roundtree, and the Fletchers made claims to their property and built temporary homes in dugouts along the prairie.

The Nicodemus Town Company produced numerous circulars to promote the town, inviting “Colored People of the United States” to come and settle in the “Great Solomon Valley.” The Reverend Roundtree became actively involved in the promotion, and worked with Benjamin “Pap” Singleton , a black carpenter from Nashville, who traveled all over distributing the circulars. Singleton, who could not read or write, distributed so many circulars that he was sometimes called the “Moses of the Colored Exodus.” The Blacks who decided to emigrate thus soon acquired the name “Exodusters ”

The black refugees associated Kansas with the Underground Railroad and the fiery abolitionist John Brown, and were particularly responsive to opportunities to settle there. Handbills and flyers distributed by the Nicodemus Town Company portrayed Nicodemus as a place for African-Americans to establish Black self-government. At the same time, railroads, needing to populate the West to create markets for their services, exaggerated the qualities of the soils and climate in this “Western Eden.”

The desperate families of the South listened with rapt attention and in the late summer of 1877, 308 railroad tickets were purchased to take them to the closest railroad point in Ellis, Kansas Still fifty-five miles away, the families walked to Nicodemus, arriving in September 1877. Within one month the first black child was born in Graham County to Mr. and Mrs. Henry Williams

Building homes along the Soloman River in dugouts, the original settlers found more disappointment and privation as they faced adverse weather conditions. In the Promised Land of Kansas, they initially lacked sufficient tools, seed, and money, but managed to survive the first winter, some by selling buffalo bones, others by working for the Kansas Pacific Railroad at Ellis, 55 miles away. Yet, others survived only with the assistance of the Osage Indians, who provided food, firewood and staples.

Though most stayed, many were disillusioned by the lack of vegetation and the starkness of the land, quickly returning to the green fields of Kentucky and Tennessee. Of those who stayed, the spring of 1878 brought hope and opportunity as the new settlers began to farm the soil.

The spring of 1878 also heralded more “Exodusters ” from the South and a local government was established, headed by “President Smith.” One woman arriving in the spring, Williana Hickman said years later of arriving at Nicodemus, “… “When we got in sight of Nicodemus the men shouted, “There is Nicodemus!” Being very sick, I hailed this news with gladness. I looked with all the eyes I had. I said, “Where is Nicodemus? I don’t see it.” My husband pointed out various smokes coming out of the ground and said, “That is Nicodemus.” The families lived in dugouts…. The scenery was not at all inviting, and I began to cry.”

Despite the living conditions and their longing for the forested hills of Kentucky, Williana and her husband Reverend Daniel Hickman stayed, organizing the First Baptist Church in a dugout with a sod structure above it. By 1880, a small, one-room, stone sanctuary had been erected at the same buy viagra kijiji site. This structure evolved from limestone to stucco, and in 1975, a new brick sanctuary was built. Today, the church still stands in Nicodemus.

When new groups of settlers arrived in Nicodemus in 1878–79 from Kentucky and Mississippi, they came prepared. Unlike the early migrants, they had the resources necessary to develop and cultivate the farmland; they came with the horse teams, plows, other farm equipment, and money that the early settlers did not have. John W. Niles, a leader in the charity movement, replaced Smith as the president of the town company. Under Niles’ leadership, a decision was made to stop seeking charity in order to encourage the ideas of industry and self-sufficiency. Additionally, the town did not want to become a destination of theExodusters, a migration of thousands of poor black farmers into Kansas. They feared that a mass influx of poor farmers would be harmful for to the community.

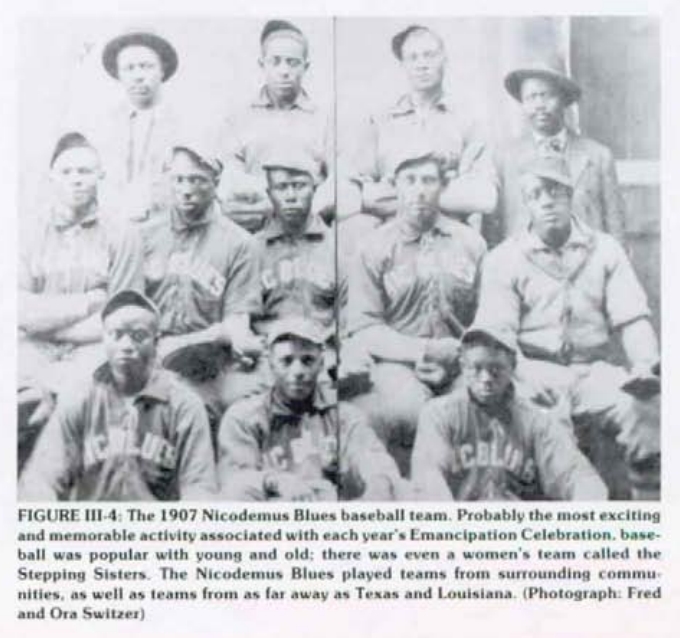

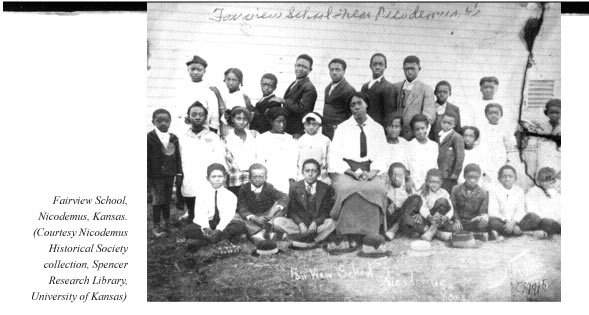

Soon the town began to grow and businesses became profitable; a hotel and two stores were established and a school and three churches were built. Social organizations such as the Grand Independent Benevolent Society of Kansans and Missouri put on dances and other celebrations for the benefit of the town. One such event was the annual celebration of England’s emancipation of slavery in the West Indies. In 1880, the election to determine the Graham County seat was held in Nicodemus, in which the town was defeated in favor of Millbrook.

Beginning in 1886 the town began another campaign of promotion. The town’s two newspapers: the Western Cyclone and the Nicodemus Enterprise were central to the new campaign. The papers sought to broaden the appeal of Nicodemus by reaching out to other populations, both black and white. Descriptions of the towns numerous social clubs, activities, celebrations, and business opportunities were spread in the hope of attracting new migrants. The town undertook a major effort to bring a railroad route through Nicodemus, passing a vote to sell $16,000 of bonds to finance the projects. Ultimately, none of the three prospective railroad companies, the Missouri Pacific, Union Pacific, and Santa Fe, brought their tracks to the town.

After the rail service failed to materialize, Zachary Fletcher, the town’s first entrepreneur, sold his town lots to the original promoter, W. R. Hill, but continued to run his businesses. Eventually, the hotel reverted to Graham County for a time but was brought back into the family in the 1920’s by Fred Switzer, a great-nephew raised by the Fletchers. When Switzer married Ora Wellington in 1921, they made the hotel their home.

By 1928, the farmers of Nicodemus were cultivating from fifty to one thousand acres each. When the seasons were favorable, the lands frequently yielded more value in wheat than the actual sale value of the land.

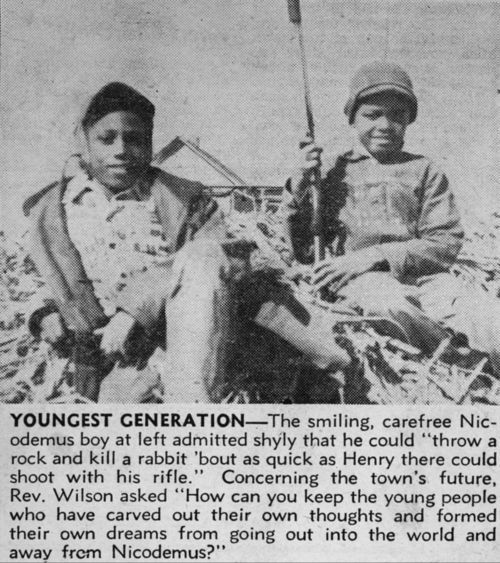

But, in 1929, the depression brought disaster to Nicodemus, as farm prices fell. Most of the young people began to leave the area during this time.

Further devastation occurred when the area faced severe droughts in 1932, 1933 and 1934, followed by the infamous dust bowl days of Kansas in the late winter and early spring of 1935. Entire families then left what had become an unproductive region.

By 1935, the small town was reduced to a population of just 76 and supported only a church, a hall, and a meagerly stocked store. Most of the marketing and trading were carried on at Bogue, about six miles away.

In 1938 a community center was built, that now hosts a National Park Service ranger, historic displays and a gift shop. The community center was a WPA project during the depression and was guilt from locally quarried limestone.

By 1950 Nicodemus was reduced to 16 inhabitants and the necessities of life had to be purchased in nearby Bogue. The post office closed in 1953.

More than a half-dozen black settlements sprung up in Kansas after the Civil War but Nicodemus was the only one to survive. Kansas’ first black settlement and Graham County’s first community, was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1976.Twenty years later, on November 12, 1996, Nicodemus was designated as a National Historical site. This legislation directs the National Park Service to assist the community in the preservation of historic structures and to interpret the history for the benefit of present and future generations.

The only remaining business is the Nicodemus Historical Society Museum, which operates sporadic hours. Pamphlets, a Walking Tour Map & Guide, and video presentations are available at the Nicodemus Community Center. Today, Nicodemus is called home to approximately 20 people.

Every year on the last weekend in July Emancipation Day is celebrated and descendants of original town settlers come home. The town is filled with people who are proud of their heritage. Events include a parade, food and celebration of heritage and family.