Good Morning POU. We continue our look at the period of history defined as the Nadir of African American History. The very violent and bleak period after the end of the Reconstruction era until the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement. A time of bleak and almost unbearable prospects for African Americans, but the descendants of slaves persevered through unimaginable horrors to keep fighting for their share of the “American” dream.

Modern historical consensus regards Reconstruction as a time of idealism and hope, with some practical achievements. The Radical Republicans who passed the 14th and 15th were, for the most part, motivated by a desire to help freedmen. African American historian W. E. B. Du Bois put this view forward in 1910, and later historians Kenneth Stampp and Eric Foner expanded it. The Republican Reconstruction governments had their share of corruption, but they benefited many whites, and were no more corrupt than Democratic governments or, indeed, Northern Republican governments.

Furthermore, the Reconstruction governments established public education and social welfare institutions for the first time, improving education for both blacks and whites, and tried to improve social conditions for the many left in poverty after the long war. No Reconstruction state government was dominated by blacks; in fact, blacks did not attain a level of representation equal to their population in any state.

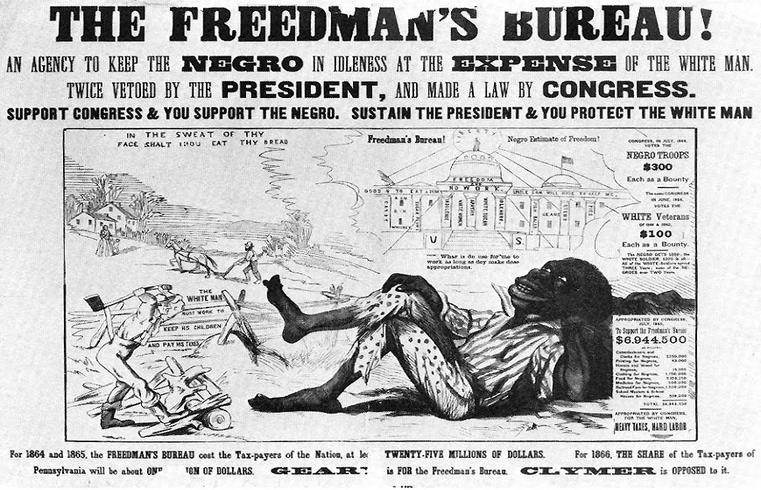

For several years after the war, the federal government, pushed by Northern opinion, showed itself willing to intervene to protect the rights of black Americans. There were limits, however, to Republican efforts on behalf of blacks: in Washington, a proposal of land reform made by the Freedmen’s Bureau which would have granted blacks plots on the plantation land they worked never came to pass. In the South, many former Confederates were stripped of the right to vote, but they resisted Reconstruction with violence and intimidation. James Loewen notes that between 1865 and 1867, when white Democrats controlled the government, whites murdered an average of one black person every day in Hinds County, Mississippi. Black schools were especially targeted: school buildings were frequently burned and teachers were flogged and occasionally murdered. The postwar terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) acted with significant local support, attacking freedmen and their white allies; the group was largely suppressed by federal efforts under the Enforcement Acts of 1870–71, but did not disappear and had a resurgence in the early twentieth century.

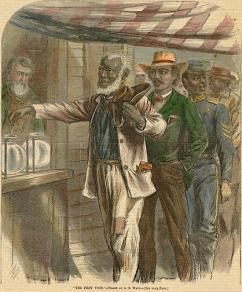

Despite these failures, however, blacks continued to vote and attend schools. Literacy soared, and many African-Americans were elected to local and statewide offices, with several serving in Congress. Because of the black community’s commitment to education, the majority of blacks were literate by 1900.

Continued violence in the South, especially heated around electoral campaigns, sapped Northern intentions. More significantly, after the long years and losses of the Civil War, Northerners had lost heart for the massive commitment of money and arms that would have been required to stifle the white insurgency. The financial panic of 1873 disrupted the economy nationwide, causing more difficulties. The white insurgency took on new life ten years after the war. Conservative white Democrats waged an increasingly violent campaign, with the Colfax and Coushatta Massacres in Louisiana in 1873 as signs. The next year saw the formation of paramilitary groups, such as the White League in Louisiana (1874) and Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, that worked openly to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt black organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voting. They invited press coverage. One historian described them as “the military arm of the Democratic Party.”

In 1874, in a continuation of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872, thousands of White League militiamen fought against New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won. They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery, took over the capitol, state house and armory for a few days, and then retreated in the face of Federal troops. This was known as the “Battle of Liberty Place”.

Northerners waffled and finally capitulated to the South, giving up on being able to control election violence. Abolitionist leaders like Horace Greeley began to ally themselves with Democrats in attacking Reconstruction governments. By 1875, there was a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. President Ulysses S. Grant, who as a general had led the Union to victory in the Civil War, initially refused to send troops to Mississippi in 1875 when the governor of the state asked him to. Violence surrounded the presidential election of 1876 in many areas, beginning a trend. After Grant, it would be many years before any President would do anything to extend the protection of the law to black people.

As noted above, white paramilitary forces contributed to whites’ taking over power in the late 1870s. A brief coalition of populists took over in some states, but conservative Democrats had returned to power after the 1880s. From 1890 to 1908, they proceeded to pass legislation and constitutional amendments to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites, with Mississippi and Louisiana creating new state constitutions in 1890 and 1895 respectively, to disenfranchise African Americans. Democrats used a combination of restrictions on voter registration and voting methods, such as poll taxes, literacy and residency requirements, and ballot box changes. The main push came from elite Democrats in the Black Belt, where blacks were a majority of voters. The elite Democrats also acted to disfranchise poor whites. African Americans were an absolute majority of the population in Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina, and represented more than 40% of the population in four other former Confederate states. Accordingly, many whites perceived African Americans as a major political threat, because in free and fair elections, they would hold the balance of power in a majority of the South.

South Carolina U.S. Senator Ben Tillman proudly proclaimed in 1900, “We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting]… we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it.”

Conservative white Democratic governments passed Jim Crow legislation, creating a system of legal racial segregation in public and private facilities. Blacks were separated in schools and the few hospitals, were restricted in seating on trains, and had to use separate sections in some restaurants and public transportation systems. They were often barred from some stores, or forbidden to use lunchrooms, restrooms and fitting rooms. Because they could not vote, they could not serve on juries, which meant they had little if any legal recourse in the system. Between 1889 and 1922, as political disfranchisement and segregation were being established, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) calculates lynchings reached their worst level in history. Almost 3,500 people fell victim to lynching, almost all of them black men.

Historian James Loewen notes that lynching emphasized the helplessness of blacks: “the defining characteristic of a lynching is that the murder takes place in public, so everyone knows who did it, yet the crime goes unpunished.” Ostensibly prompted by black attacks or threats to white women, scholars and journalists have shown that lynchings arose out of economic competition and desire by competing whites for social control. African American civil rights activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett conducted one of the first systematic studies of the subject. She found blacks were “lynched for anything or nothing” – for wife-beating, stealing hogs, being “saucy to white people”, sleeping with a consenting white woman – for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was a system of social terrorism.

Blacks who were economically successful faced reprisals or sanctions. When Richard Wright tried to train to become an optometrist and lens-grinder, the other men in the shop threatened him until he was forced to leave. In 1911 blacks were barred from participating in the Kentucky Derby because African Americans won more than half of the first twenty-eight races. Through violence and legal restrictions, whites often prevented blacks from working as common laborers, much less as skilled artisans or in the professions. Under such conditions, even the most ambitious and talented black people found it extremely difficult to advance.

This situation called into question the views of Booker T. Washington, the most prominent black leader during the early part of the nadir. He had argued that black people could better themselves by hard work and thrift. He believed they had to master basic work before going on to college careers and professional aspirations. Washington believed his programs trained blacks for the lives they were likely to lead and the jobs they could get in the South.

However, as W. E. B. Du Bois pointed out,

it is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for working men and property-owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage.

Washington had always (though often clandestinely) supported the right of black suffrage, and had fought against disfranchisement laws in Georgia, Louisiana, and other Southern states. This included secretive funding of litigation resulting in Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), which lost due to Supreme Court reluctance to interfere with states’ rights.