Today we take a look at the case of The Wilmington Ten.

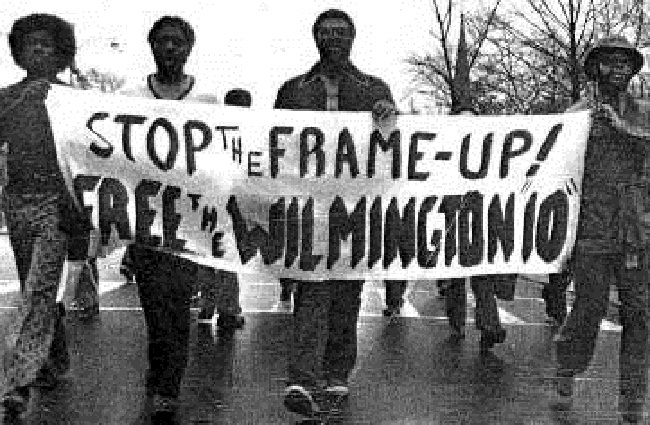

The Wilmington Ten were nine young men and a woman, who were convicted in 1971 in Wilmington, North Carolina of arson and conspiracy, and served nearly a decade in jail. The case became an international cause célèbre, in which many critics of the city’s actions characterized the activists as political prisoners.

Amnesty International took up the case in 1976 and provided legal counsel to appeal the convictions. In 1980 in Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir., 1980), the convictions were overturned by the federal appeals court, on the grounds that the prosecutor and the trial judge had both violated the defendants’ constitutional rights.

In the 1960s and 1970s, black residents of Wilmington, North Carolina were unhappy with the lack of progress in implementing integration and other civil rights reforms legally achieved by the American Civil Rights Movement. Many struggled with poverty and lack of opportunity. The 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. increased racial tensions, with a rise in violence, including the arson of several white-owned businesses.

Racial tension increased after the 1969 integration of Wilmington high schools, as the city closed the black Williston Industrial High School, a source of community pride. It laid off black teachers, principals, and coaches, transferring students to other schools. There was little preparation of whites or blacks for the changes. The school administration resisted meeting with the students to hear their grievances, including separation from friends and the lack of opportunity to play sports in new schools. Several clashes between white and black students had resulted in a number of arrests and expulsions.

In response to tensions, members of a Ku Klux Klan chapter and other white supremacist groups began patrolling the streets. They hung an effigy of the white superintendent of the schools and cut his phone lines. Street violence broke out between them and black men.

Students decided to boycott the high schools in January 1971. In February, the United Church of Christ sent Reverend Benjamin Chavis, Jr., from their Commission for Racial Justice, to Wilmington to try to calm the situation and work with the students. He preached non-violence to them and met with students regularly at Gregory Congregational Church to discuss black history, as well as to organize the boycott.

Arson at Mike’s Grocery and trial

On February 6, 1971, Mike’s Grocery, a white-owned business, was firebombed. Firefighters responding to the fire said they were shot at by snipers from the roof of the nearby Gregory Congregational Church. Chavis and several students had been meeting at the church, which also held other people. The neighborhood erupted in rioting that lasted through the next day, in which two people died.

The governor of the state called up the National Guard, whose forces entered the church on February 8 and removed the suspects. They claimed to have found ammunition in the building. The violence resulted in two deaths, six injuries, and over $500,000 in property damage.

Chavis and nine others, eight young black men who were high school students, and an older white woman, an anti-poverty worker, were arrested on charges of arson related to the grocery. Based on testimony of two black men, they were tried and convicted of arson and conspiracy in connection with the firebombing of Mike’s Grocery. They were sentenced to a total of 282 years in prison.

The “Ten” and their sentences:

- Benjamin Chavis (age 24) – 34 years

- Connie Tindall (age 21) – 31 years

- Marvin “Chili” Patrick (age 19) – 29 years

- Wayne Moore (age 19) – 29 years

- Reginald Epps (age 18) – 28 years

- Jerry Jacobs (age 19) – 29 years

- James “Bun” McKoy (age 19) – 29 years

- Willie Earl Vereen (age 18) – 29 years

- William “Joe” Wright, Jr. (age 19) – 29 years

- Ann Shepard (age 35) – 15 years

Trial and sentencing

At the time, the state’s case against the Wilmington Ten was seen as controversial both in the state of North Carolina and in the United States. One witness testified that he was given a minibike in exchange for his testimony against the group. Another witness, Allen Hall, had a history of mental illness and had to be removed from the courthouse after recanting on the stand under cross examination.

The group were convicted of the charges. The men’s sentences ranged from 29 years to 34 years for arson, severe proscription for a fire in which no one died. Ann Shepard of Auburn, New York, age 35, received 15 years as an accessory before the fact and conspiracy to assault emergency personnel. The youngest of the group, Earl Vereen, was 18 years old at the time of his sentencing. Reverend Chavis was the oldest of the men at age 24. The sentences totaled 282 years.

International response

Several national magazines, including Time, Newsweek, Sepia and The New York Times Magazine, published articles in the late 1970s on the trial and its aftermath. When then President Jimmy Carter admonished the Soviet Union in 1978 for holding political prisoners, the Soviets cited the Wilmington Ten as an example of American political imprisonment.

Appeals

Amnesty International took on the Wilmington Ten case in 1976. They classified the eight men still in prison as among 11 black men incarcerated in the U.S. who were considered to be political prisoners, under the definition in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

In 1976 and 1977, three key prosecution witnesses recanted their testimony. In 1977 60 Minutes aired a special about the case, suggesting that the evidence against the Wilmington Ten was fabricated. In 1978, the New York Times reporter Wayne King published an investigatory article; based on testimony of a witness whose anonymity he protected, he said that perhaps the prosecution had framed a guilty man, as his source said that he had committed the crimes at the behest of Chavis.

In 1980, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, a federal court, overturned the convictions, as it determined that (1) the prosecutor failed to disclose exculpatory evidence, in violation of the defendants’ due process rights [the Brady rule]; and (2) the trial judge erred by limiting the cross-examination of key prosecution witnesses about special treatment the witnesses received in connection with their testimony, in violation of the defendants’ 6th Amendment right to confront the witnesses against them. Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir. 1980).

A group called the Wilmington Ten Foundation for Social Justice was established to work to improve conditions in the city.

Pardon

In May 2012, Benjamin Chavis and six surviving members of the group petitioned North Carolina governor Beverly Perdue for a pardon. The NAACP was supporting the pardon, as well as compensation to be paid to the men and their survivors for their years in jail. On December 22, 2012 The New York Times published an editorial titled, “Pardons for the Wilmington Ten” that urged Governor Perdue to “finally pardon” the group of civil rights activists. Perdue granted a pardon of innocence on December 31, 2012 which qualified each of the ten to state compensation of $50,000 per year of incarceration.

The claims were approved by the NC Industrial Commission and signed off on by the Attorney General, Roy Cooper’s office in May 2013. Total compensation was $1,113,605: Ben Chavis received $244,470.00, Marvin Patrick received $187,984.00 with most of the remaining rewards being $175,000.00 each. Four of the Wilmington Ten are now deceased and their families received no compensation.

In 2015, The North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled that the families of the four members of the Wilmington 10 that were deceased, who were eventually pardoned for their roles in Wilmington race riots didn’t deserve money from the state. In its ruling, the court noted that because the pardons were issued after the quartet had died, there was no claim on their behalf that would have passed on to their estate.

“Because Jacobs, Shepard, Tindall, and Wright received no pardons of innocence during their lifetimes, no claims … existed to survive to their estates,” the court wrote.