Pittsburgh’s Hill District seemed like New York City to Thomas Burks, who moved from the North Side to the Lower Hill during the late 1920s. Burks, 89, said Fullerton Street and Wylie Avenue — known as “the crossroads of the world” for jazz and entertainment — were alive with clubs like the Blue Note, Bambola Social Club and Loendi Club.

“When I was a young man, it was like being in Times Square,” Burks recalled. “The whole area was lit up all night long.”

Urban renewal initiatives of the 1950s wiped out Pittsburgh’s “Little Harlem” and triggered neighborhood decay that destroyed the center of black culture between New York and Chicago.

City and community leaders are working to revitalize the Hill with aggressive plans for new housing, business and social and cultural programs, but those who remember the neighborhood zenith lament that the new Hill will never equal the old.

“There’s places that were here before, and they are never going to be here again,” said Zandra Gloster, 73. ‘We didn’t have to go Downtown.’

The neighborhood stretching from Washington Place, Downtown, to Herron Hill was densely populated with whites from dozens of European countries who lived next door to blacks who migrated from the South.

It was home to the Pittsburgh Crawfords Negro Leagues baseball club; the Pittsburgh Courier, one of America’s largest black newspapers boasting a circulation of 450,000; and black artists such as Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson.

By 1950, 53,648 people lived in Hill neighborhoods, according to the city Planning Department. That dwindled to 10,450, according to 2010 census figures.

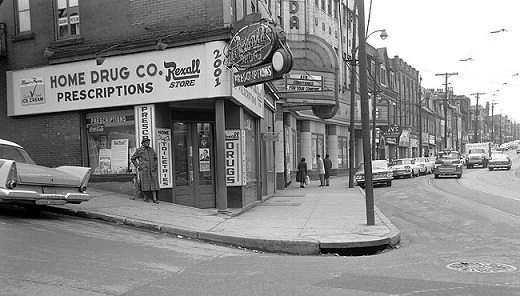

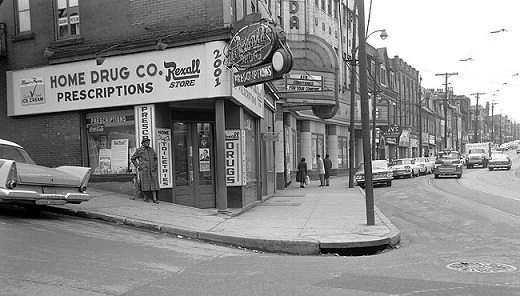

“You might have a Jewish family living to the right of you and an Italian family living to the left of you,” said Gloster, who grew up on Colwell Street. “We had a lot of kids; we had a lot of schools. We had drugstores and shoe stores, a department store, hotels, theaters and all that stuff on the Hill. If we didn’t want to, we didn’t have to go Downtown to shop.”

She said Jewish-owned businesses on Logan Street carried everything from live chickens to fresh fish and meats.

Pete Verse, 85, who owned the Workman’s Club, said the likes of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald played in such venues as the Crawford Grill, Pythian Temple and Savoy Ballroom on any night.

“They would play until early in the morning, and it wouldn’t cost me nothing but bottles of gin, or whatever they drank, and something to eat,” Verse said..’

The neighborhood began its slide when the city cut the Hill off from Downtown with the construction of Crosstown Boulevard and demolition of the Lower Hill for the Civic Arena.

“Approximately 90 percent of the buildings in the area are substandard and have long outlived their usefulness, and so there would be no social loss if they were all destroyed,” then-City Councilman George E. Evans wrote in 1943.

In the 1950s, the city leveled 1,300 structures and displaced more than 8,000 people, which included 1,239 black and 312 white families, according to a history by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Thirty-five percent of residents went to public housing projects, 31 percent rented from private landlords and 8 percent bought homes, according to the history. Few received relocation compensation.

Community leaders are attempting to rebuild the Hill with new housing, plans for a revitalized Centre Avenue commercial district and redevelopment of the 28-acre Civic Arena site for offices, stores and apartments.

The new Oakhill community brought about 700 apartments and town homes to the site of the former Allequippa Terrace housing project, and work is under way on the $180 million federally funded redevelopment of the former Addison Terrace public housing complex.

Read the full article at the Pittsburgh Tribune