h/t GreenLadyHere

The Defiant One: Why You Should Know Civil Rights Icon Gloria Richardson (the root.com)

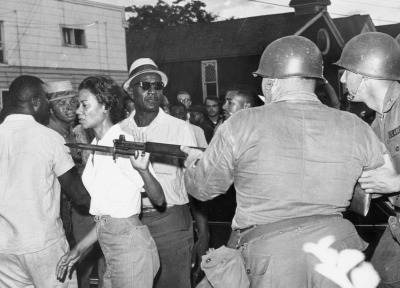

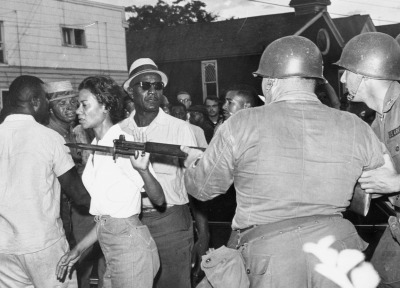

Some called her “Glorious Gloria.” Others referred to her as the second coming of Harriet Tubman. Coincidentally, activist Gloria Richardson was just 24 minutes away from a stop on the Underground Railroad when an iconic photo of her defiantly pushing away the bayonet of a National Guardsman was taken during a 1963 protest in Cambridge, Md. Her fearless, revolutionary deeds have become an inspiration for many black activists today.

“I got out there first and I ran across the line,” Richardson, 93, tells The Root about that fateful encounter with the U.S. National Guard. “He was about to stick me in the back with the bayonet; I couldn’t believe it.”

As head of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee, Richardson was one of the few women in a leadership role during the civil rights movement. And while she received accolades for her work in Cambridge at the March on Washington in August 1963, like many women in the movement, Richardson was not permitted to speak, even though she was listed on the program. Her story is the subject of a new biography, slated for publication in 2016, titled The Struggle Is Eternal: Gloria Richardson and Black Liberation.

“Gloria was a different type of strength. Nobody was going to stop her or her community from getting her basic human rights,” says Judy Richardson (no relation), a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and producer of the documentary Eyes on the Prize.

Gloria Richardson, who was born in Baltimore, moved at age 6 to Cambridge, where her parents ran a successful hardware store. She attended Howard University at 16, graduating in 1942 with a degree in sociology. By 1948 she was raising her family after marrying Harry Richardson, who worked as a schoolteacher. Her move toward activism was sparked in 1961, when the Freedom Riders made buy viagra nigeria their way to Cambridge. Richardson says that’s when things “started stirring up.”

At the time, blacks in the city lived in the 2nd Ward and faced severe economic inequality. The town, which was one-third African American, was segregated, and many public spaces were off-limits to black residents.

Richardson’s daughter, Donna, became a part of SNCC to help desegregate the city’s public spaces. Gloria Richardson and other community members establishedthe adult-led Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee in 1962. The organization, which was the only SNCC affiliate not run by students, focused on public-housing discrimination and unequal health care for blacks.

“Cambridge was built on the SNCC model,” Richardson says. “It may have been 400-500 people who helped with the movement.” But CNAC did differ from SNCC in one key area: “We weren’t nonviolent,” Richardson says. “White folks would come there shooting at your houses, and people responded.”

As the black community became more vocal in demanding equal rights, tension began to escalate. In June 1963, businesses went up in flames as both blacks and whites took up arms, Richardson says. “It was like a little war, really,” she says. “In a certain period of time, it was almost every night.”

Because of the increasing violence, “the mayor got scared and called for the National Guard,” she says. That same year, Attorney General Robert Kennedy called for black Cambridge leaders to come to Washington, D.C.

Kennedy, along with other government officials, brokered the “Treaty of Cambridge” in July 1963 to help bring calm to the city. But Richardson told Kennedy that the demonstrators were not coming out of the streets.

Cambridge soon saw visits from former SNCC Chairman and black power activist Stokely Carmichael. Cambridge faced another huge rebellion in 1967 after Richardson invited Carmichael’s successor, H. Rap Brown, whose speech sparked a violent reaction, leading to the torching of two blocks in Cambridge.