Good Morning POU!

Today’s featured story is a reprint from The Washington Post.

300 Men March is an organization founded by a young man determined to teach others the mistakes of his past and take back his neighborhood in Baltimore. Philanthropy is not about a dollar amount, but about people like this.

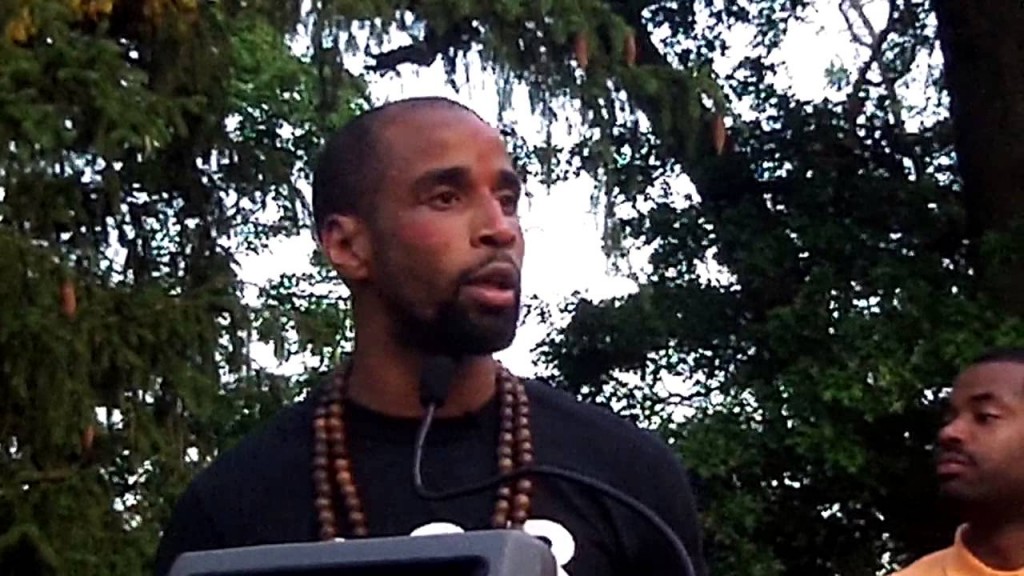

The sun was setting over Baltimore as three dozen men converged on a parking lot on the city’s east side, assembling before their leader, a small, muscular African American man, his fleeting smile revealing flashes of gold. Munir Bahar’s gilded dental grill evoked his years as a brawling, guncarrying drug dealer, a period before he earned an accounting degree and became a selfstyled crusader against the mayhem he once practiced.

“Gentlemen,” said Bahar, 34, greeting the squad, which was about to embark on its summertime ritual: a Friday night walk across four miles of torn sidewalks, past vacant husks of rowhouses and residents long accustomed to violence and despair. “If you don’t believe in the mission, take the shirts off,” Bahar told the men, each one wearing a black tee with “300” across the chest. “If I scare you away,” he said, “this ain’t for you.”

A nationwide spate of fatal encounters between police and African Americans over the past year — in places such as Ferguson, New York, Cleveland and, more recently, Baltimore — has created a rare platform for streetwise organizers such as Bahar to push their own remedies for containing violence. Unlike civic leaders and academics who address the issue from loftier perches, Bahar and his counterparts argue that a more potent approach is in faceto-face appeals to the men most likely to kill and be killed.

A tax consultant when he isn’t operating a nonprofit group that teaches kids physical fitness, Bahar walks Baltimore’s most distressed streets with his followers, urging black men to reject gun violence and join their campaign. Yet nearly three months after the National Guard restored order to Baltimore, progress is elusive, with the city’s political leaders and police scrambling to halt the carnage that defines its poorest neighborhoods.

Bahar declared his own “state of emergency” in May as the city’s homicide toll climbed. On any given day, his quest can seem futile and even naive, as it did when a 7 year old was shot to death or when a 16 year old was killed. But the mayhem only fuels Bahar’s rawtoned resolve as he demands to know what African American men are doing to protect their communities.

Where were they, he asks, when neighborhoods needed protection during the rioting? Where were they in May, when the city logged 42 homicides, the most for any month since the 1970s? And where were they on this humid Friday night, as he prepared a group he named the “300 Men March” to set out on a walk that drew only 39 volunteers?

Later, he would describe the turnout as “pathetic.” But on this night, as darkness settled over Baltimore, Bahar said: “Gentlemen! Roll out!”

On April 27, as rioting spread in Baltimore, Bahar and his men in their “300” Tshirts raced toward the epicenter of the chaos, the intersection of Pennsylvania and North avenues, “because we knew we had to do something.” “It was like being dropped into the jungle,” he said, describing burning buildings, a “lady hit in the face with a shovel,” a guy on top of a truck imitating Michael Jackson’s moonwalk.

Bahar’s group has been a presence in Baltimore since 2013, when a surge in homicides drove him and others to walk through neighborhoods and convene on corners to disseminate the message that black men “must stop killing each other.” His experience selling drugs sets him apart from others who have mounted campaigns in past years, including ministers and politicians who have staged marches and vigils as Baltimore has remained among the country’s most violent cities. “Because I’m the one,” Bahar said by way of explaining his determination. “I’m the one who can do it.”

Combating the city’s violent culture is not without risks. More than a decade ago, a couple and their five children were killed when their rowhouse in east Baltimore was firebombed after the kids’ mother testified against a drug dealer.

Yet the potential for danger, he said, is less disturbing than remaining silent. “What kind of man would I be?” he asked. He makes no apologies for his passion and his blunt delivery, which has rankled even those who support his cause. Appearing before a congressional panel, he chided city leaders “for a serious lack of courage to approach even our young guys who have tattoos, gold teeth, who wear their pants down.”

“We have a lot of fancy forums and galas and town hall meetings,” he told the panel. “We talk and talk and talk. Meanwhile, our young people are not connected.” As he left the hearing, he told a reporter: “This was BS. This thing cost money. It would have been better spent directly on the people.” His appearances on television during the riot and his focus on self-reliance prompted a business executive to offer a $25,000 donation.

Yet others view Bahar’s on the ground approach — and his unwillingness to address issues such as police conduct and racism — as marginal in a city beset by an entrenched history of socioeconomic ills. “It’s one piece of the puzzle, but the puzzle is much bigger,” said Lawrence Brown, a Morgan State University professor active in Baltimore politics. “Neighborhoods that are deeply affected by years and years of neglect have a much more powerful role in explaining how and why violence is such a feature in disinvested communities.” Or as Baltimore City Council member Carl Stokes asked, “Is any murder abated from walking around?”

“We need the police and the FBI in Baltimore,” Stokes said. “We need action.” Bahar dismissed the criticism, refusing to take on issues that he says distract from his main concern. “This is a state of emergency,” he said. “We are the last hope this city has. If the community doesn’t step up, the military will come in.”

On another night, Bahar summoned the 300 to a school gymnasium, where for two hours he reviewed what he described as protocols for their walks through neighborhoods. “No sitting down,” he commanded as they arrived, a few dozen mostly African American men of varying ages who formed a circle around him. The “Street Engagement Unit,” as he called the group, included a lawyer, a financial analyst, an English tutor, an IT technician, a city councilman, a corrections officer and more than a couple of men who have tangled with police. The circle did not include women, because Bahar believes only men are suited for the work.

“Men and women have different roles,” he would explain later. “Like the heart and the lung — they work together. Both equally important, but they have different roles.” Every seven minutes, an alarm signaled that it was time for the men to drop to the floor for a round of pushups, a ritual that prompted more and more grunting as the night wore on. In between, Bahar reminded the men: “We’re not vigilantes. We’re not police.”

He recited a list of orders, including “We don’t go into any residences for nothing,” and “We don’t carry weapons,” and “No handcuffs, no nightsticks,” and “Do not talk excessively loud,” and “Do not become engaged in political or religious discussions.” “We’re not telling young guys, ‘Pull your pants up, take care of your kids, stop selling drugs,’ ” he said. “We’re only addressing the violence. Whatever to get them away from the idea of using a gun.” “Our job is to deliver a message,” he said. “It’s also to preserve our safety. Yeah, it’s thugs who will shoot you in two seconds. We have no room for foolishness. We’re in the fing ’hood.” Anyone not following his orders, he repeated, “will be dismissed.”

Bahar’s sense of Baltimore is rooted in his upbringing. A single mother’s son, he was 13 when he shot another youngster with a BB gun. Twice he was expelled from middle school for fighting. At 16, he spent nine months in juvenile detention for more fighting. At 17, he sold crack and weed before being arrested for stealing a car, drug dealing and gun possession. At 20, Bahar said, he was a student at Morgan State when God “came into my head” and said: “It’s time to lead the world. It’s time to change the world.” “It’s not explainable, because it’s not common,” he said, recalling the moment. “You may understand it, you may not. There’s no science about it. It’s when a human being develops or matures, when you reach a certain point of clarity.”

He studied accounting, immersed himself in the martial arts and started a mentoring program that eventually turned into the nonprofit that runs fitness programs for kids. Then he founded the 300 Men group with City Council member Brandon Scott. The name was inspired by the movie “300” depicting the Battle of Thermopylae, in which 300 Spartans died trying to hold off a massive Persian army. They organized an annual march across the city, as well as weekly summer walks through violent neighborhoods, an approach that evokes similar efforts from the past.

Thirty years ago, then U.S. Rep. Parren Mitchell stood on Baltimore street corners handing out thousands of “Us Killing Us = Genocide” bumper stickers in his own campaign against black-on-black violence. The Rev. Willie E. Ray, a Baltimore activist who for decades has been holding prayer vigils at homicide scenes, said the potential of the 300 Men is limited without offering more than a march. “As soon as you walk away, people are going to laugh at you,” Ray said. “People are looking for jobs and opportunity.” Bahar hopes to establish teams of 30 men in 10 neighborhoods to disseminate the group’s message and recruit more volunteers.

But, in an environment of overwhelming apathy, he knows that trying to enlist new recruits can be as frustrating as trying to raise money. In recent months, he has altered his strategy, offering $100 a week to a dozen teenagers who qualify for a program of physical and leadership training. The program became possible when a prominent developer saw Bahar on TV during the riot and the aftermath, talking about the importance of altering attitudes in the black community.

“I’m not expecting him to change the world,” said the developer, Theo Rodgers. “But you have to start with something.” Three weeks after the riot, Rodgers traveled to Bahar’s office and offered a $25,000 donation. In the next 48 hours, the challenge he faced became even more clear: Baltimore police recorded 19 shootings, including three that were fatal.

A month later, on a Friday night in June, Bahar led the 300 Men group along Lyndale Avenue in east Baltimore. He told a man on a stoop that they are trying to “get more men to urge the calming of the violence.” “Hoping y’all can join us,” Bahar said. “Maybe after I get my life together,” the man replied. As the group turned onto Elmora Avenue, Michael Hitchens, 51, a corrections officer wearing a “300” Tshirt, walked past the house where his sister Michelle was shot to death two years ago. Marlo Hargrove, 42, another 300 member, eyed the young men in tank tops and was reminded of his own past selling drugs. “I see me in them,” he said. “You weren’t a man until you had stories to tell.”

In the distance, a baby wailed, music pounded, motorists honked, children laughed, dogs barked and motorcycles rumbled. A water bug crawled by. “God!” a woman shouted as they passed. “Men! Men! Men! Y’all is rainin’!” Moments later, Bahar touched his iPhone’s record button and delivered into the camera a message he would later post on social media. “I don’t see the leaders of Baltimore out in the streets where communities need them the most,” he said. “This is where it’s at. This is Baltimore. This is the work that’s needed to give our people some damn hope.” “We’re going to keep walking,” he said, and on they went.

Read more about Bahar’s efforts to operate an after school program (COR) for troubled young men here.