Nine years before the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v Board of Education, Froebel High School in Gary, Indiana accepted 200 African-American students. Not all of the white kids were happy. A thousand angry teens banded together and protested the school’s decision by skipping school. And that’s when Frank Sinatra showed up.

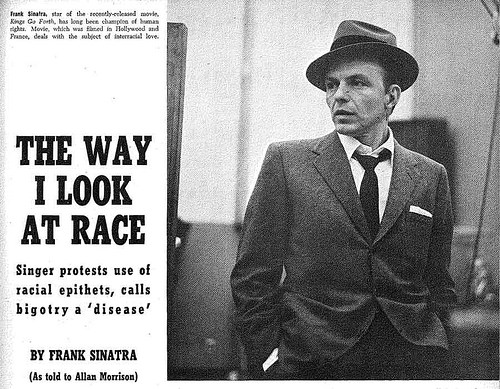

Earlier that year, Sinatra had starred in an Academy-Award winning short called The House I Live In. The movie featured Sinatra lecturing a group of boys on how all Americans are equal, regardless of race or religion. With the film fresh in his mind, Sinatra flew out to Froebel High School and spoke to the entire student body, explaining the evils of racism. Before he left, Sinatra had the students take a pledge of tolerance and even sang the theme to “The House I Live In,” a ballad with lyrics like: “The children in the playground / The faces that I see / All races and religions / That’s America to me.”

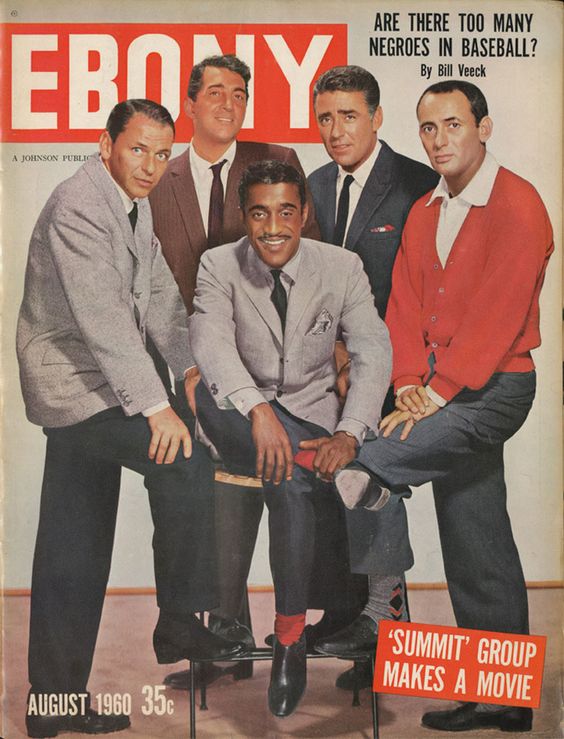

In his heyday, he performed with almost every black idol of jazz, blues and swing: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, Sammy Davis Jr. They all became friends.

By adapting their music for white audiences, Sinatra gained more fame and money than any black artist could achieve in a segregated society. But he gave credit where it belonged–with the African-Americans who pioneered and perfected the genres. Sinatra often said Holiday was his “greatest single musical influence.” Of Ella: “She, in my opinion, is the greatest of all contemporary jazz singers.”

On tour, Sinatra refused to play at clubs unless blacks were permitted to attend. He would not sleep in a hotel that banned his black colleagues. There’s a famous story about how he escorted Lena Horne to the Stork Club, a whites-only hot spot, and insisted they admit her. After much hand-wringing, they did.