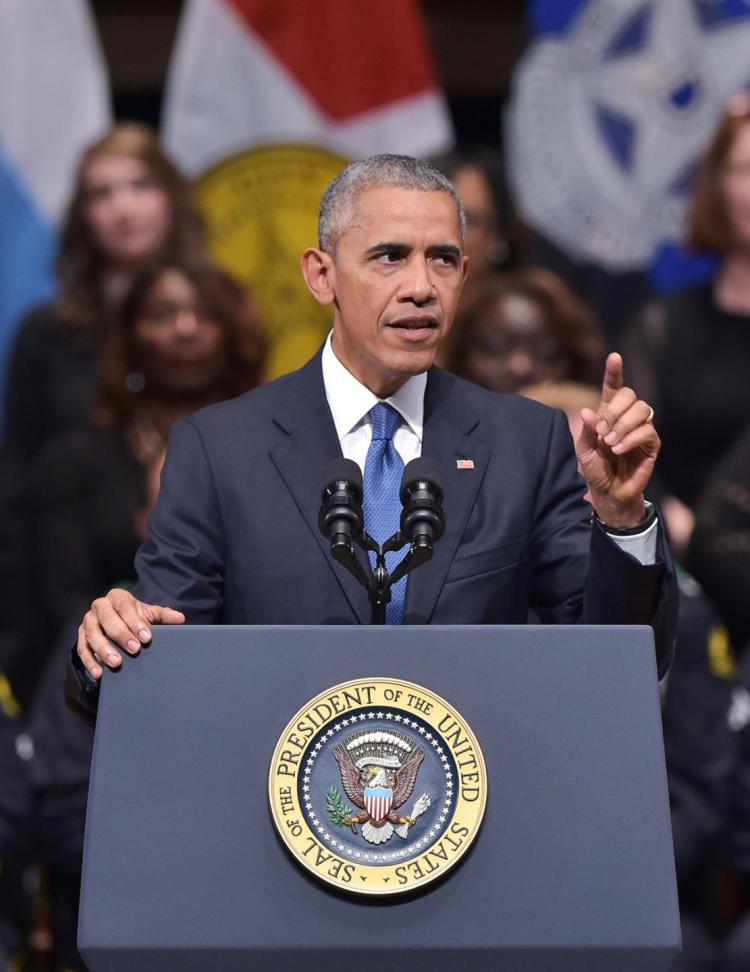

President Obama delivered this message at a funeral for slain Dallas officers Brent Thompson, Patrick Zamarripa, Michael Krol, Lorne Ahrens and Michael Smith on Tuesday.

Scripture tells us that in our sufferings, there is glory, because we know that suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope. Sometimes the truths of these words are hard to see. Right now, those words test us because the people of Dallas, people across the country are suffering.

We’re here to honor the memory and mourn the loss of five fellow Americans, to grieve with their loved ones, to support this community, and pray for the wounded, and to try and find some meaning amidst our sorrow.

For the men and women who protect and serve the people of Dallas, last Thursday began like any other day. Like most Americans, each day you get up, probably have too quick a breakfast, kiss your family goodbye and you head to work.

But your work and the work of police officers across the country is like no other. For the moment you put on that uniform, you have answered a call that at any moment, even in the briefest interaction, may put your life in harm’s way.

Lorne Ahrens, he answered that call. So did his wife, Katrina, not only because she was the spouse of a police officer, but because she’s a detective on the force. They have two kids. Lorne took them fishing. And he used to proudly go to their school in uniform.

On the night before he died, he bought dinner for a homeless man. And the next night, Katrina had to tell their children that their dad was gone. “They don’t get it yet,” their grandma said. “They don’t know what to do quite yet.”

Michael Krol answered that call. His mother said, he knew the dangers of the job, but he never shied away from his duty. He came 1,000 miles from his home state of Michigan to be a cop in Dallas, telling his family, this is something I wanted to do.

And last year, he brought his girlfriend back to Detroit for Thanksgiving. And it was the last time he’d see his family.

Michael Smith answered that call. In the Army, and over almost 30 years working for the Dallas Police Association, which gave him the appropriately named Cop’s Cop Award. A man of deep faith; when he was off duty, he could be found at church or playing softball with his two girls.

Today, his girls have lost their dad, for God has called Michael home.

Patrick Zamarippa, he answered that call. Just 32, a former altar boy who served in the Navy and dreamed of being a cop. He liked to post videos of himself and his kids on social media. On Thursday night, while Patrick went to work, his partner, Christy, posted a photo of her and their daughter at a Texas Rangers game, and tagged the department so that he could see it while on duty.

Brent Thompson answered that call. He served his country as a Marine. And years later, as a contractor, he spent time in some of the most dangerous parts of Iraq and Afghanistan. And then a few years ago, he settled down here in Dallas for a new life of service as a transit cop.

And just about two weeks ago, he married a fellow officer, their whole life together waiting before them.

Like police officers across the country, these men and their families shared a commitment to something larger than themselves. They weren’t looking for their names to be up in lights. They’d tell you the pay was decent, but wouldn’t make you rich. They could have told you about the stress and long shifts. And they’d probably agree with Chief Brown when he said that cops don’t expect to hear the words “thank you” very often, especially from those who need them the most.

No. The reward comes in knowing that our entire way of life in America depends on the rule of law, that the maintenance of that law is a hard and daily labor, that in this country we don’t have soldiers in the streets or militias setting the rules.

Instead, we have public servants, police officers, like the men who were taken away from us. And that’s what these five were doing last Thursday when they were assigned to protect and keep orderly a peaceful protest in response to the killing of Alton Sterling of Baton Rouge and Philando Castile of Minnesota.

They were upholding the constitutional rights of this country.

For a while, the protests went on without incident. And despite the fact that police conduct was the subject of the protest, despite the fact that there must have been signs or slogans or chants with which they profoundly disagreed, these men and this department did their jobs like the professionals that they were.

In fact, the police had been part of the protest planning. Dallas P.D. even posted photos on their Twitter feeds of their own officers standing among the protesters. Two officers, black and white, smiled next to a man with a sign that read “no justice, no peace.”

And then around nine o’clock, the gunfire came. Another community torn apart; more hearts broken; more questions about what caused and what might prevent another such tragedy.

I know that Americans are struggling right now with what we’ve witnessed over the past week. First, the shootings in Minnesota and Baton Rouge, the protests. Then the targeting of police by the shooter here, an act not just of demented violence, but of racial hatred.

All of it has left us wounded and angry and hurt. This is — the deepest faultlines of our democracy have suddenly been exposed, perhaps even widened. And although we know that such divisions are not new, though they’ve surely been worse in even the recent past, that offers us little comfort.

Faced with this violence, we wonder if the divides of race in America can ever be bridged. We wonder if an African-American community that feels unfairly targeted by police and police departments that feel unfairly maligned for doing their jobs, can ever understand each other’s experience.

We turn on the TV or surf the internet, and we can watch positions harden and lines drawn and people retreat to their respective corners, and politicians calculate how to grab attention or avoid the fallout. We see all this, and it’s hard not to think sometimes that the center won’t hold and that things might get worse.

I understand. I understand how Americans are feeling. But Dallas, I’m here to say we must reject such despair. I’m here to insist that we are not as divided as we seem. And I know that because I know America. I know how far we’ve come against impossible odds.

I know we’ll make it because of what I’ve experienced in my own life; what I’ve seen of this country and its people, their goodness and decency, as president of the United States. And I know it because of what we’ve seen here in Dallas, how all of you out of great suffering have shown us the meaning of perseverance and character and hope.

When the bullets started flying, the men and women of the Dallas police, they did not flinch and they did not react recklessly. They showed incredible restraint. Helped in some cases by protesters, they evacuated the injured, isolated the shooter, saved more lives than we will ever know.

We mourn fewer people today because of your brave actions.

“Everyone was helping each other,” one witness said. And it wasn’t about black or white. Everyone was picking each other up and moving them away.

See, that’s the America I know. The police helped Shetamia Taylor as she was shot trying to shield her four sons. She said she wanted her boys to join her to protest the incidents of black men being killed.

She also said to the Dallas P.D., thank you for being heroes. And today, her 12-year-old son wants to be a cop when he grows up. That’s the America I know.

In the aftermath of the shooting, we’ve seen Mayor Rawlings and Chief Brown, a white man and a black man with different backgrounds, working not just to restore order and support a shaken city, a shaken department, but working together to unify a city with strength and grace and wisdom.

And in the process, we’ve been reminded that the Dallas Police Department has been at the forefront of improving relations between police and the community.

The murder rate here has fallen. Complaints of excessive force have been cut by 64 percent. The Dallas Police Department has been doing it the right way.

And so, Mayor Rawlings and Chief Brown, on behalf of the American people, thank you for your steady leadership. Thank you for your powerful example. We could not be prouder of you.

These men, this department, this is the America I know. And today in this audience, I see people who have protested on behalf of criminal justice reform grieving alongside police officers. I see people who mourn for the five officers we lost, but also weep for the families of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. In this audience, I see what’s possible.

I see what’s possible when we recognize that we are one American family, all deserving of equal treatment. All deserving equal respect. All children of God. That’s the America I know.

Now, I’m not naive. I have spoken at too many memorials during the course of this presidency. I’ve hugged too many families who have lost a loved one to senseless violence. And I’ve seen how a spirit of unity, born of tragedy, can gradually dissipate, overtaken by the return to business as usual, by inertia and old habits and expediency.

I see how easily we slip back into our old notions, because they’re comfortable, we’re used to them. I’ve seen how inadequate words can be in bringing about lasting change. I’ve seen how inadequate my own words have been. And so, I’m reminded of a passage in John’s Gospel, “let us love, not with words or speech, but with actions and in truth.”

If we’re to sustain the unity, we need to get through these difficult times. If we are to honor these five outstanding officers who we lost, then we will need to act on the truths that we know. That’s not easy. It makes us uncomfortable, but we’re going to have to be honest with each other and ourselves.

We know that the overwhelming majority of police officers do an incredibly hard and dangerous job fairly and professional. They are deserving of our respect and not our scorn.

When anyone, no matter how good their intentions may be, paints all police as biased, or bigoted, we undermine those officers that we depend on for our safety. And as for those who use rhetoric suggesting harm to police, even if they don’t act on it themselves, well, they not only make the jobs of police officers even more dangerous, but they do a disservice to the very cause of justice that they claim to promote.

We also know that centuries of racial discrimination, of slavery, and subjugation, and Jim Crow; they didn’t simply vanish with the law against segregation. They didn’t necessarily stop when a Dr. King speech, or when the civil rights act or voting rights act were signed. Race relations have improved dramatically in my lifetime. Those who deny it are dishonoring the struggles that helped us achieve that progress. But we know…