Good Morning POU!

We continue to look at the history of African Americans and the ideology of Communism, as well as Socialism and Marxism.

The Communist Party USA, ideologically committed to foster a Socialist revolution in the United States, played a significant role in defending the civil rights of African Americans during its most influential years of the 1930s and 1940s. In that period, the African-American population was still concentrated in the South, where it was largely disenfranchised, excluded from the political system, and oppressed under Jim Crow laws.

The Sixth Congress of the Comintern (Communist International) held in 1928 changed the party’s policy drastically; it claimed that blacks in the United States were a separate national group and that black farmers in the South were an incipient revolutionary force. The Comintern ordered the party to press the demand for a separate nation for blacks within the so-called “Black Belt“, a swath of counties with a majority-black population extending from eastern Virginia and the Carolinas through central Georgia, Alabama, the delta regions of Mississippi and Louisiana and the coastal areas of Texas. The party leadership was deeply divided into rival factions, with each eager to show its fealty to the Comintern’s understanding of conditions in the United States. It promoted the nationalist policy.

Other left organizations ridiculed this policy, and it did not receive wide support from African Americans, either in the urban north or in the South. They had more immediate, pressing problems and the CPUSA had little foothold. While the party continued to give lip service to the goal of national self-determination for blacks, particularly in its theoretical writings, it largely ignored that demand in its practical work.

The party sent organizers to the Deep South for the first time in the late 1920s. The party focused its efforts, for the most part, on very concrete issues: organization of miners, steelworkers and tenant farmers, dealing with utility shutoffs, evictions, jobs, and unemployment benefits; trying to raise awareness of and prevent lynchings, and challenging the pervasive system of Jim Crow. It hoped to appeal to both white and black workers, starting in Birmingham the most industrialized city in Alabama. Black workers were attracted to the party, but whites stayed away.

The party also worked in rural areas to organize sharecroppers and tenant farmers, who worked under an oppressive system. In Camp Hill, Alabama in 1931 white vigilantes responded by murdering one leader, and local authorities charged and prosecuted black farmers for murder who had tried to fight off the mob. Attorneys with the International Labor Defense succeeded in having the charges dropped against all of the defendants. The Share Croppers’ Union, formed after these events, continued organizing. After leading a strike in 1934 that won higher prices for cotton pickers despite intense hostility from local authorities and businesses, its membership increased to nearly 8,000.

In Alabama and other parts of the nation, the International Labor Defense, which focused on civil rights issues, had up to 2,000 members. The Sharecroppers’ Union had up to 12,000 members in Alabama. Other related organizations were the International Workers Order, the League of Young Southerners, and the Southern Negro Youth Congress. Through these organizations, the CPUSA could be seen to “touch the lives easily of 20,000 people.”

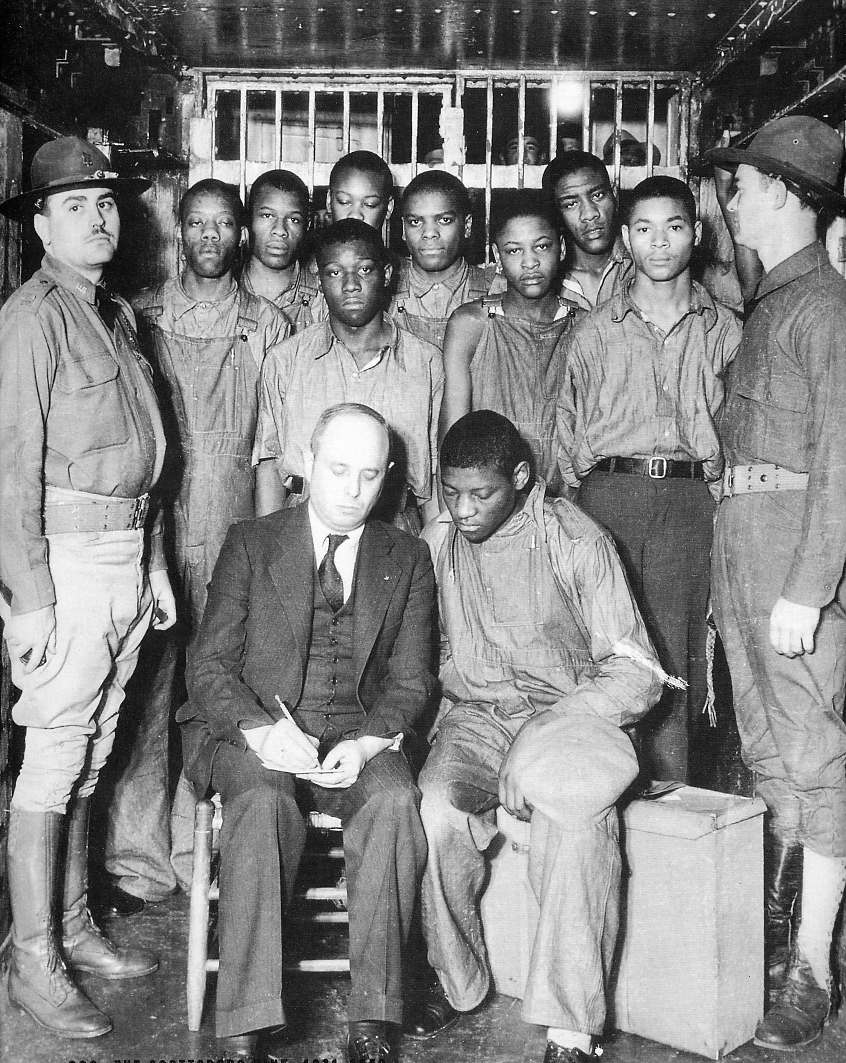

The Scottsboro Boys Case

The party’s most widely reported work in the South was its defense, through the International Labor Defense (ILD), of the “Scottsboro Boys“, nine black men arrested in 1931 in Scottsboro, Alabama after a fight with some white men also riding the rails. They were convicted and sentenced to death for allegedly raping two white women on the same train. None of the defendants had shared the same boxcar as either of the women they were charged with raping.

The International Labor Defense was the first to offer its assistance. William L. Patterson, a black attorney who had left a successful practice to join the Communist Party, returned from training in the Soviet Union to run the ILD. After fierce disputes with the NAACP, with the ILD seeking to mount a broad-based political campaign to free the nine while the NAACP followed a more legalistic strategy, the ILD took control of the defendants’ appeals. The ILD attracted national press attention to the case, and highlighted the racial injustices in the region.

The ILD successfully overturned the men’s convictions on appeal to the United States Supreme Court, which held in Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) that the State’s failure to provide the defendants with counsel in a capital case violated their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. The ILD’s battles with the NAACP continued when the cases returned to Alabama for retrial. The NAACP blamed the ILD for the lead defendant’s being convicted and sentenced to death in the retrial. The NAACP later agreed to join with the ILD in defending the nine after other black organizations and a number of NAACP branches attacked it for that position, so the tensions never disappeared.

The ILD retained control of the second round of appeals. It won reversals of these convictions in Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935), on the ground that the exclusion of blacks from the jury pool had violated the defendants’ constitutional rights. In a third retrial, all of the defendants were convicted.

Angelo Herndon

The Scottsboro defense was one of the ILD’s many cases in the South at that time. The ILD defended Angelo Herndon, a Communist Party activist sentenced to death by the State of Georgia for treason due to his advocacy of national self-determination for blacks in the Black Belt. The ILD also demanded retribution from state governments for the families of lynching victims, for their failure to protect blacks. It pushed for due process for criminal defendants. For a period of time in the early and mid-1930s, the ILD was the most active defender of blacks’ civil rights in the South; it was the most popular party organization among African Americans.

The League of Struggle for Negro Rights, founded in 1930 as the successor to the ANLC, was particularly active in organizing support for the Scottsboro defendants. It also campaigned for a separate black nation in the South and against police brutality and Jim Crow laws. In addition, it advocated a more general policy of opposition to international fascism and support for the Soviet Union. Langston Hughes became its President in 1934. Harry Haywood was its General Secretary.