GOOD MORNING PRAGOBOTS!

We continue our series on African-American Bankers…

REV. WILLIAM WASHINGTON BROWNE

(1849-1897)

The True Reformers Bank

Richmond, VA

William Washington Browne was a slave, a Union solder during the American Civil War (1861–1865), a teacher, a Methodist minister, and the founder of Richmond’s Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers, an African American fraternal organization. As leader of the True Reformers, Browne strived to help members live productive lives without depending upon the white community. By establishing insurance that provided members with sick and death benefits and by encouraging members to purchase land and engage in practices of temperance and thrift, Browne believed that blacks in the post–Civil War South could thrive. Browne’s enterprising mind helped lead the True Reformers in creating and organizing a bank which became the nation’s first chartered black financial institution and a model that others, such as Maggie Lena Walker, would follow. Browne died in 1897 and the True Reformers initially continued to prosper, but the order collapsed in the wake of the scandalous failure of its bank in 1910.

Browne was born on October 20, 1849, in Habersham County, Georgia, the son of Joseph Browne and Mariah Browne.

His parents were Virginia slaves who met after being sold and transported to Georgia. Browne’s original given name was

Ben. When he was about eight years old he was moved to a plantation near Memphis, Tennessee, and then sold to a horse trader. After his sale Browne adopted the given names William Washington. He escaped from bondage in 1862 after the United States Army occupied Memphis and subsequently served first on a Union gunboat and then in the infantry. After being discharged in 1866 Browne attended school in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, before returning to the South in 1869 to teach school. He met Mary A. Graham while teaching in Alabama, and they were married on August 16, 1873.

Browne’s education won him immediate respect in the black community. He further enhanced his standing throughout

Georgia and Alabama by speaking out against the Ku Klux Klan during the early part of the 1870s and by becoming a leading temperance advocate. Browne sought the endorsement in Alabama of the Independent Order of Good Templars, a white temperance society. The Good Templars refused to be formally associated with blacks but offered Browne a compromise according to which he would receive a charter and sponsorship under the separate name of the Grand United Order of True Reformers. Browne accepted, quit his teaching position, and began his rise to national prominence.

A superb speaker and organizer, Browne soon founded fifty local chapters, or subfountains, which was the number of chapters Good Templar guidelines required for the establishment of a state organization, called a grand fountain. To enhance his authority and expand his audience, Browne looked to the church. The Colored Methodist Episcopal Church Conference of Alabama licensed him to preach and ordained him in August 1876.

In 1876 the Grand Lodge of Good Templars of Virginia invited Browne to lead its new branch of the True Reformers in Richmond. Although a bastion of black temperance, the city proved quite a challenge. After an auspicious start, interest in the Reformers quickly dwindled. Browne returned to Alabama, where he developed plans to transform his temperance society into an insurance organization with a bank, but he could not obtain the state charter necessary for the enterprise. In 1880 he moved to Richmond to take control of the weak Grand Fountain of Virginia and there continued to work on his plan to create a business empire out of the True Reformers. Shortly after his arrival in Richmond he also served for a time as pastor of the Leigh Street Methodist Episcopal Church.

Browne’s first insurance effort, the Mutual Benefit and Relief Plan of the United Order of True Reformers, was a poorly planned savings and death-benefit system that depended on continual recruitment of new members to pay its beneficiaries, which made it little more than a Ponzi scheme. In January 1884, the General Assembly passed a bill incorporating the Supreme Fountain Grand United Order of True Reformers, and in 1885 after further study the True Reformers instituted the first insurance plan of an African American fraternal society that was based on actuarial calculations of life expectancies. Members and prospective members paid varying fees for their insurance according to their ages.

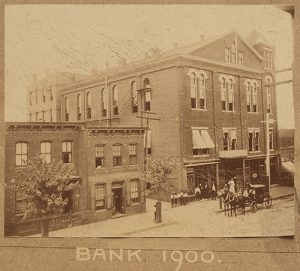

The insurance system proved quite profitable and soon supported other Reformer enterprises. Browne established the Rosebud department to instill principles of thrift in members’ children. He also began to expand the order’s business operations by purchasing real estate in Richmond and elsewhere as the order spread across Virginia and the eastern United States. Browne’s most daring move came on March 2, 1888, when the order received a state charter for the nation’s first black-owned, black-operated bank. The True Reformers’ bank prospered for years and was the only bank in Richmond able to continue honoring checks during the financial panic of 1893.

In May 1891, the Reformers dedicated a new hall that housed the various operations of the order. The building contained the bank, several business offices, three stores, four large meeting rooms, and a concert hall. The largest building in the city owned by blacks, it was also constructed entirely by African Americans. By that time the order’s membership approached 10,000, and it soon acquired a hotel, published a weekly newspaper, ran a general merchandise store, and operated a home for aged members. From its humble beginnings as a temperance society Browne built the order into the largest black fraternal society and black-owned business in the country. The impressive new True Reformers’ Hall in Richmond symbolized the order’s premier position.

Success notwithstanding, Browne engendered controversy in Richmond’s African American community. His conservatism and enormous ego irritated many of his contemporaries, most notably John Mitchell Jr., the editor of the Richmond Planet . Two incidents in 1895 particularly raised hackles. After Mitchell and a black Massachusetts legislator presented themselves in March at the governor’s mansion for a reception tendered to the visiting Massachusetts Committee on Mercantile Affairs, Browne wrote to a local newspaper criticizing their behavior and explaining his own less confrontational view of race relations: “Legal equality and cordial relation—to the extent of building up the negro race—are the desires of respectable and sensible negroes; and they are as much opposed to social equality between whites and blacks as are the whites themselves.” The following September Browne arranged to sell his copyrighted plans for the True Reformers to the order for $50,000. Many in Richmond, and Mitchell in particular, regarded the transaction as an overwhelming proof of Browne’s greed.

Nonetheless, Browne’s standing was widely recognized. He was one of only eight men, including Booker T. Washington, selected to represent African Americans at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. The True Reformers’ exhibition there enhanced Browne’s stature and that of his order in what proved to be his last major achievement. In 1897 physicians discovered a cancerous tumor and urged him to have the affected arm amputated, but he refused. The cancer spread quickly, and Browne died in Washington, D.C., on December 21, 1897. He was buried in Sycamore Cemetery, and his funeral was one of the largest ever seen in Richmond’s black community. Browne bequeathed his estate to his widow, except for small legacies to the boy and girl they had adopted. After his death the True Reformers initially continued to prosper, but the order collapsed in the wake of the scandalous failure of its bank in 1910.

(SOURCE: Encyclopedia Virginia)