GOOD MORNING POU!

We continue our look at African-American Ghost Stories.

THE GRAY WOLF’S HA’NT

From The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People, Movements, and Motifs:

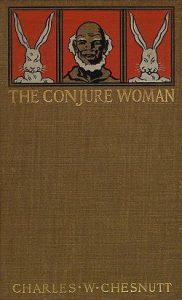

In the works of African American writers, though, slaves use ghost stories to undermine white authority. Uncle Julius, from Charles Chesnutt’s collection The Conjure Woman (1899), tells the plantation owners of “The Gray Wolf’s Ha’nt” in order to protect his favorite source of honey from demolition.

An excerpt from “The Gray Wolf’s Ha’nt”:

“I’m glad you came, Julius,” I responded. “We don’t want to go driving, of course, in the rain, but I should like to consult you about another matter. I’m thinking of taking in a piece of new ground. What do you imagine it would cost to have that neck of woods down by the swamp cleared up?”

The old man’s countenance assumed an expression of unwonted seriousness, and he shook his head doubtfully.

“I dunno ’bout dat, suh. It mought cos’ mo’, en it mought cos’ less, ez fuh ez money is consarned. I ain’ denyin’ you could cl’ar up dat trac’ er Ian’ fer a hund’ed er a couple er hund’ed dollahs,—ef you wants ter cl’ar it up. But ef dat ‘uz my trac’ er Ian’, I would n’ ‘sturb it, no, suh, I would n’; sho ‘s you bawn, I would n’.”

“But why not?” I asked.

“It ain’ fittin’ fer grapes, fer noo groun’ nebber is.”

“I know it, but”—

“It ain’ no yeathly good fer cotton, ‘ca’se it’s top low.”

“Perhaps so; but it will raise splendid corn.”

“I dunno,” rejoined Julius deprecatorily. “It’s so nigh de swamp dat de ‘coons’ll eat up all de cawn.”

“I think I’ll risk it,” I answered.

“Well, suh,” said Julius, “I wushes you much joy er yo’ job. Ef you has bad luck er sickness er trouble er any kin’, doan blame me. You can’t say ole Julius did n’ wa’n you.”

“Warn him of what, Uncle Julius?” asked my wife.

“Er de bad luck w’at follers folks w’at ‘sturbs dat trac’ er Ian’. Dey is snakes en sco’pions in dem woods. En ef you manages ter ‘scape de p’isen animals, you is des boun’ ter hab a ha’nt ter settle wid,—ef you doan hab two.”

“Whose haunt?” my wife demanded, with growing interest.

“De gray wolf’s ha’nt, some folks calls it,—but I knows better.”

“Tell us about it, Uncle Julius,” said my wife. “A story will be a godsend to-day.”

It was not difficult to induce the old man to tell a story, if he were in a reminiscent mood. Of tales of the old slavery days he seemed indeed to possess an exhaustless store,—some weirdly grotesque, some broadly humorous; some bearing the stamp of truth, faint, perhaps, but still discernible; others palpable inventions, whether his own or not we never knew, though his fancy doubtless embellished them. But even the wildest was not without an element of pathos,—the tragedy, it might be, of the story itself; the shadow, never absent, of slavery and of ignorance; the sadness, always, of life as seen by the fading light of an old man’s memory.

“Way back yander befo’ de wah,” began Julius, “ole Mars Dugal’ McAdoo useter own a nigger name’ Dan. Dan wuz big en strong en hearty en peaceable en good-nachu’d most er de time, but dange’ous ter aggervate. He alluz done his task, en nebber had no trouble wid de w’ite folks, but woe be unter de nigger w’at ‘lowed he c’d fool wid Dan, fer he wuz mos’ sho’ ter git a good lammin’. Soon ez eve’ybody foun’ Dan out, dey did n’ many un ’em ‘temp’ ter ‘sturb ‘im. De one dat did would ‘a’ wush’ he had n’, ef he could ‘a’ libbed long ernuff ter do any wushin’.

“It all happen’ dis erway. Dey wuz a cunjuh man w’at libbed ober t’ other side er de Lumbe’ton Road. He had be’n de only cunjuh doctor in de naberhood fer lo! dese many yeahs, ‘tel ole Aun’ Peggy sot up in de bizness down by de Wim’l’ton Road. Dis cunjuh man had a son w’at libbed wid ‘im, en it wuz dis yer son w’at got mix’ up wid Dan,—en all ’bout a ‘oman.

“Dey wuz a gal on de plantation name’ Mahaly. She wuz a monst’us lackly gal,—tall en soopl’, wid big eyes, en a small foot, en a lively tongue, en w’en Dan tuk ter gwine wid ‘er eve’ybody ‘lowed dey wuz well match’, en none er de yuther nigger men on de plantation das’ ter go nigh her, fer dey wuz all feared er Dan.

“Now, it happen’ dat dis yer cunjuh man’s son wuz gwine ‘long de road one day, w’en who sh’d come pas’ but Mahaly. En de minute dis man sot eyes on Mahaly, he ‘lowed he wuz gwine ter hab her fer hisse’f. He come up side er her en ‘mence’ ter talk ter her; but she didn’ paid no ‘tention ter ‘im, fer she wuz studyin’ ’bout Dan, en she did n’ lack dis nigger’s looks nohow. So w’en she got ter whar she wuz gwine, dis yer man wa’n’t no fu’ther ‘long dan he wuz w’en he sta’ted.

“Co’se, atter he had made up his min’ fer ter git Mahaly, he ‘mence’ ter ‘quire ‘roun’, en soon foun’ out all ’bout Dan, en w’at a dange’ous nigger he wuz. But dis man ‘lowed his daddy wuz a cunjuh man, en so he ‘d come out all right in de een’; en he kep’ right on atter Mahaly. Meanw’iles Dan’s marster had said dey could git married ef dey wanter, en so Dan en Mahaly had tuk up wid one ernudder, en wuz libbin’ in a cabin by deyse’ves, en wuz des wrop’ up in one ernudder.

“But dis yer cunjuh man’s son did n’ ‘pear ter min’ Dan’s takin’ up wid Mahaly, en he kep’ on hangin’ ‘roun’ des de same, ‘tel fin’lly one day Mahaly sez ter Dan, sez she:—

“‘I wush you ‘d do sump’n ter stop dat free nigger man fum follerin’ me ‘roun’. I doan lack him nohow, en I ain’ got no time fer ter was’e wid no man but you.’

“Co’se Dan got mad w’en he heared ’bout dis man pest’rin’ Mahaly, en de nex’ night, w’en he seed dis nigger comin’ ‘long de road, he up en ax’ ‘im w’at he mean by hangin’ ‘roun’ his ‘oman. De man did n’ ‘spon’ ter suit Dan, en one wo’d led ter ernudder, ‘tel bimeby dis cunjuh man’s son pull’ out a knife en sta’ted ter stick it in Dan; but befo’ he could git it drawed good, Dan haul’ off en hit ‘im in de head so ha’d dat he nebber got up. Dan ‘lowed he ‘d come to atter a w’ile en go ‘long ’bout his bizness, so he went off en lef ‘im layin’ dere on de groun’.

“De nex’ mawnin’ de man wuz foun’ dead. Dey wuz a great ‘miration made ’bout it, but Dan did n’ say nuffin, en none er de yuther niggers had n’ seed de fight, so dey wa’n’t no way ter tell who done de killin’. En bein’ ez it wuz a free nigger, en dey wa’n’t no w’ite folks ‘speshly int’rusted, dey wa’n’t nuffin done ’bout it, en de cunjuh man come en tuk his son en kyared ‘im ‘way en buried ‘im.

“Now, Dan had n’ meant ter kill dis nigger, en w’iles he knowed de man had n got no mo’ d’n he desarved, Dan ‘mence’ ter worry mo’ er less. Fer he knowed dis man’s daddy would wuk his roots en prob’ly fin’ out who had killt ‘is son, en make all de trouble fer ‘im he could. En Dan kep’ on studyin’ ’bout dis ‘tel he got so he did n’ ha’dly das’ ter eat er drink fer fear dis cunjuh man had p’isen’ de vittles er de water. Fin’lly he ‘lowed he ‘d go ter see Aun’ Peggy, de noo cunjuh ‘oman w’at had moved down by de Wim’l’ton Road, en ax her fer ter do sump’n ter pertec’ ‘im fum dis cunjuh man. So he tuk a peck er ‘taters en went down ter her cabin one night.

“Aun’ Peggy heared his tale, en den sez she:—

“‘Dat cunjuh man is mo’ d’n twice’t ez ole ez I is, en he kin make monst’us powe’ful goopher. W’at you needs is a life-cha’m, en I’ll make you one ter-morrer; it’s de on’y thing w’at’ll do you any good. You leabe me a couple er ha’rs fum yo’ head, en fetch me a pig ter-morrer night fer ter roas’, en w’en you come I’ll hab de cha’m all ready fer you.’

“So Dan went down ter Aun’ Peggy de nex’ night,—wid a young shote,—en Aun’ Peggy gun ‘im de cha’m. She had tuk de ha’rs Dan had lef wid ‘er, en a piece er red flannin, en some roots en yarbs, en had put ’em in a little bag made out’n ‘coon-skin.

“‘You take dis cha’m,’ sez she, ‘en put it in a bottle er a tin box, en bury it deep unner de root er a live-oak tree, en ez long ez it stays dere safe en soun’, dey ain’ no p’isen kin p’isen you, dey ain’ no rattlesnake kin bite you, dey ain’ no sco’pion kin sting you. Dis yere cunjuh man mought do one thing er ‘nudder ter you, but he can’t kill you. So you neenter be at all skeered, but go ‘long ’bout yo’ bizness en doan bother yo’ min’.’

“So Dan went down by de ribber, en ‘way up on de bank he buried de cha’m deep unner de root er a live-oak tree, en kivered it up en stomp’ de dirt down en scattered leaves ober de spot, en den went home wid his min’ easy.

“Sho’ ’nuff, dis yer cunjuh man wukked his roots, des ez Dan had ‘spected he would, en soon l’arn’ who killt his son. En co’se he made up his min’ fer ter git eben wid Dan. So he sont a rattlesnake fer ter sting ‘im, but de rattlesnake say de nigger’s heel wuz so ha’d he could n’ git his sting in. Den he sont his jay-bird fer ter put p’isen in Dan’s vittles, but de p’isen did n’ wuk. Den de cunjuh man ‘low’ he’d double Dan all up wid de rheumatiz, so he could n’ git ‘is ban’ ter his mouf ter eat, en would hafter sta’ve ter def; but Dan went ter Aun’ Peggy, en she gun ‘im a’ ‘intment ter kyo de rheumatiz. Den de cunjuh man ‘lowed he ‘d bu’n Dan up wid a fever, but Aun’ Peggy tol’ ‘im how ter make some yarb tea fer dat. Nuffin dis man tried would kill Dan, so fin’lly de cunjuh man ‘lowed Dan mus’ hab a life-cha’m….

You can read the full story, as well as other stories from The Conjure Woman, here.

To learn more about Charles Chesnutt, click here.