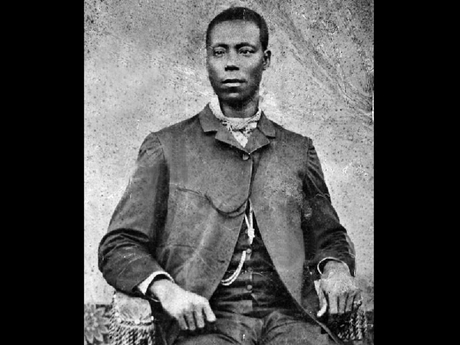

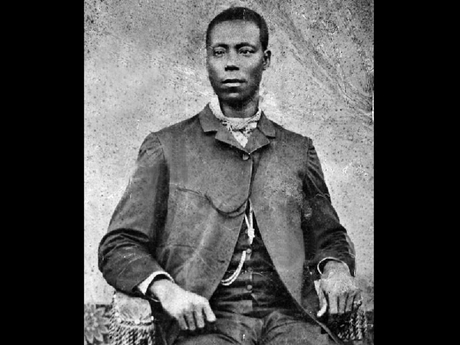

Thomas L. Jennings (1791 – February 12, 1856) was an African-American tradesman and abolitionist in New York City, New York. He operated and owned a tailoring business. In 1821 he was one of the first African Americans to be granted a patent for his method of dry cleaning, With the proceeds of his invention he bought his wife and children’s freedom then continued his civil rights work.

Jennings became active in working for his race and civil rights for the African-American community. In 1831, he was selected as assistant secretary to the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which met in June of that year. He helped arrange legal defense for his daughter, Elizabeth Jennings, in 1854 when she challenged a private streetcar company’s segregation of seating and was arrested. She was defended by the young Chester Arthur and won her case the next year.

With two other prominent African-American leaders, Jennings organized the Legal Rights Association in 1855 in New York, which raised challenges to discrimination and organized legal defense for court cases. He founded and was a trustee of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, a leader in the African-American community.[

Thomas L. Jennings was born free to a free African-American family in New York City. As a youth, he learned a trade as a tailor. He built a business and married a woman named Elizabeth, who was born in 1798 in Delaware into slavery and died March 5, 1873. Under New York’s gradual abolition law of 1799, she was converted to the status of an indentured servant and was not eligible for full emancipation until 1827. It freed slave children born after July 4, 1799, but only after they had served “apprenticeships” of twenty-eight years for men and twenty-five for women (far longer than traditional apprenticeships, designed to teach a young person a craft), thus compensating owners for the future loss of their property.[

He and his wife had three children: Matilda Jennings (b. 1824, d. 1886), Elizabeth Jennings (b. March 1827 d. June 5, 1901), and James E. Jennings (b. 1832). Matilda Jennings was a dressmaker and wife of James A. Thompson, a Mason. Elizabeth Jennings was the wife of Charles Graham, whom she married on June 18, 1860. James E. Jennings was a public school teacher.

Jennings built a business as a tailor and was well-respected in the community. He spent his early earnings on legal fees to purchase his wife and some of their children out of slavery. Their daughter Elizabeth Jennings was born free on July 11, 1827, and became a schoolteacher and church organist.[

Jennings also supported the abolitionist movement and became active in working for civil rights of free African-Americans. He was active on issues related to emigration to other countries; opposing colonization in Africa, as proposed by the American Colonization Society; and supporting the expansion of suffrage for African-American men.

Thomas Jennings was the first African American to receive a patent, on March 3, 1821. His patent was for a dry-cleaning process called “dry scouring”. … Thomas L. Jennings Dry Scouring technique created modern-day dry cleaning.

Jennings was a leader in the cause of abolitionism and African-American civil rights. After his daughter, Elizabeth Jennings, was forcibly removed from a “whites only” streetcar in New York City, he organized a movement against racial segregation in public transit in the city; the services were provided by private companies. Elizabeth Jennings won her case in 1855. Along with James McCune Smith and Rev. James W.C. Pennington, her father created the Legal Rights Association in 1855, a pioneering minority-rights organization. Its members organized additional challenges to discrimination and segregation and gained legal representation to take cases to court. A decade after Elizabeth Jennings won her case, New York City streetcar companies stopped practicing segregation.[