Happy New Year’s Eve, POU! Stay safe tonight if you are attending any NYE celebrations. On this last day of 2019, we continue to take a look at renowned African-American Photographers.

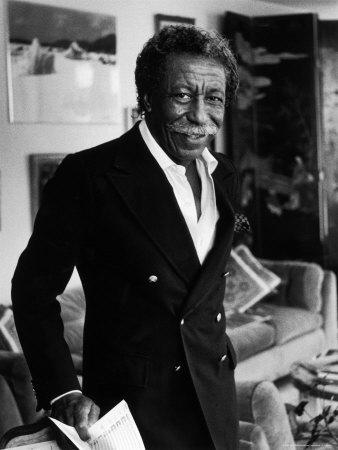

Gordon Parks was one of the seminal figures of twentieth-century photography. A humanitarian with a deep commitment to social justice, he left behind a body of work that documents many of the most important aspects of American culture from the early 1940s up until his death in 2006, with a focus on race relations, poverty, Civil Rights, and urban life. In addition, Parks was also a celebrated composer, author, and filmmaker who interacted with many of the most prominent people of his era—from politicians and artists to celebrities and athletes.

“It is an honor to preserve the work and legacy of Gordon Parks who was not only an American treasure but a friend,” said Peter Kunhardt, President of The Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation. “I am pleased that my father’s vast 19th collection and his best friend’s work will be preserved together.” This is exactly what Gordon hoped for,” said Gene Young, his former wife, and executor of his estate. “His work will be in good hands and we are all going to work hard to make it available for future generations.”

Born into poverty and segregation in Kansas in 1912, Parks was drawn to photography as a young man when he saw images of migrant workers published in a magazine. After buying a camera at a pawnshop, he taught himself how to use it and despite his lack of professional training, he found employment with the Farm Security Administration (F.S.A.), which was then chronicling the nation’s social conditions. Parks quickly developed a style that would make him one of the most celebrated photographers of his age, allowing him to break the color line in professional photography while creating remarkably expressive images that consistently explored the social and economic impact of racism.

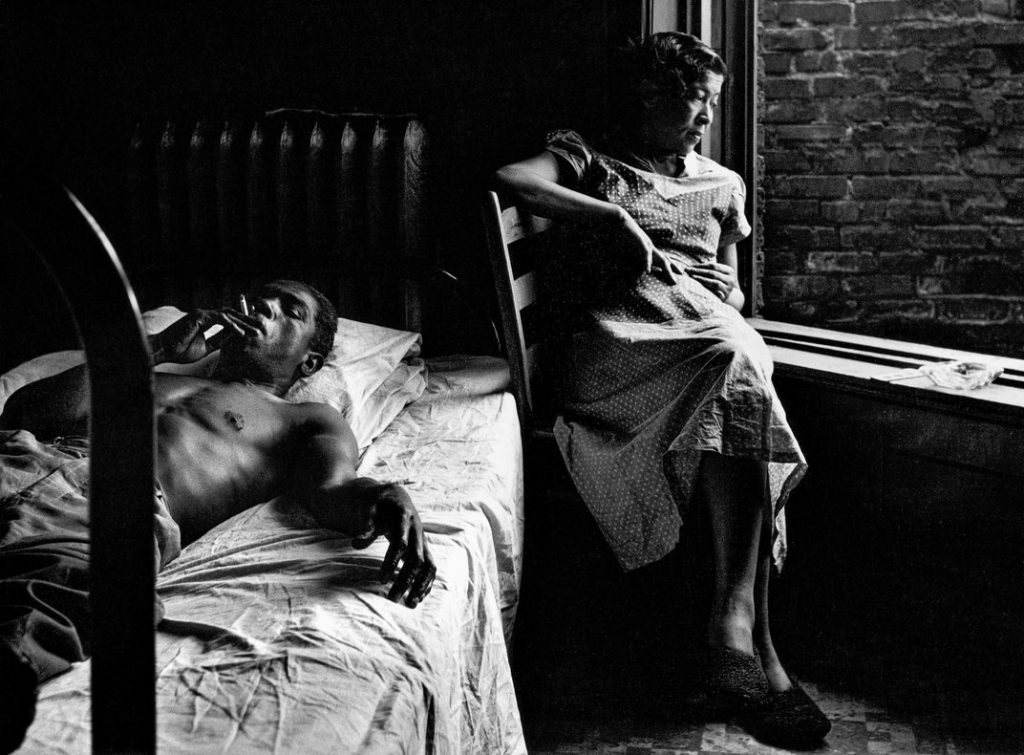

When the F.S.A. closed in 1943, Parks became a freelance photographer, balancing work for fashion magazines with his passion for documenting humanitarian issues. His 1948 photo essay on the life of a Harlem gang leader won him widespread acclaim and a position as the first African American staff photographer and writer for Life Magazine, then by far the most prominent photojournalist publication in the world. Parks would remain at Life Magazine for two decades, chronicling subjects related to racism and poverty, as well as taking memorable pictures of celebrities and politicians (including Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and Stokely Carmichael).

His most famous images, such as Emerging Man, 1952, and American Gothic, 1942, capture the essence of activism and humanitarianism in mid-twentieth-century America and have become iconic images, defining their era for later generations. They also rallied support for the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, for which Parks himself was a tireless advocate as well as a documentarian.

Parks spent much of the last three decades of his life expanding his style, conducting experiments with color photography. He continued working up until his death in 2006, winning numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts in 1988, and over fifty honorary doctorates. He was also a noted composer and author, and in 1969, became the first African American to write and direct a Hollywood feature film based on his bestselling novel The Learning Tree. This was followed in 1971 by the hugely successful motion picture Shaft.

The core of his accomplishment, however, remains his photography the scope, quality, and enduring national significance of which is reflected throughout the Collection. According to Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Center at Harvard University, “Gordon Parks is the most important black photographer in the history of photojournalism. Long after the events that he photographed have been forgotten, his images will remain with us, testaments to the genius of his art, transcending time, place and subject matter.”

Parks moved from job to job, developing a freelance portrait and fashion photographer sideline. He began to chronicle the city’s South Side black ghetto and in 1941 an exhibition of those photographs won Parks a photography fellowship with the Farm Security Administration. Working as a trainee under Roy Stryker, Parks created one of his best-known photographs, American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (named after the Grant Wood painting American Gothic). The photo shows a black woman, Ella Watson, who worked on the cleaning crew for the FSA building, standing stiffly in front of an American flag, a broom in one hand and a mop in the background.

Parks had been inspired to create the picture after encountering repeated racism in restaurants and shops, following his arrival in Washington, D.C. Upon viewing it, Stryker said that it was an indictment of America, and could get all of his photographers fired; he urged Parks to keep working with Watson, however, leading to a series of photos of her daily life. Parks, himself, said later that the first image was unsubtle and overdone; nonetheless, other commentators have argued that it drew strength from its polemical nature and its duality of victim and survivor, and so has affected far more people than his subsequent pictures of Watson.