Good Morning POU!

Today we are featuring the works of Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun.

Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun in front of L9 Center for the Arts which they founded in 2007.

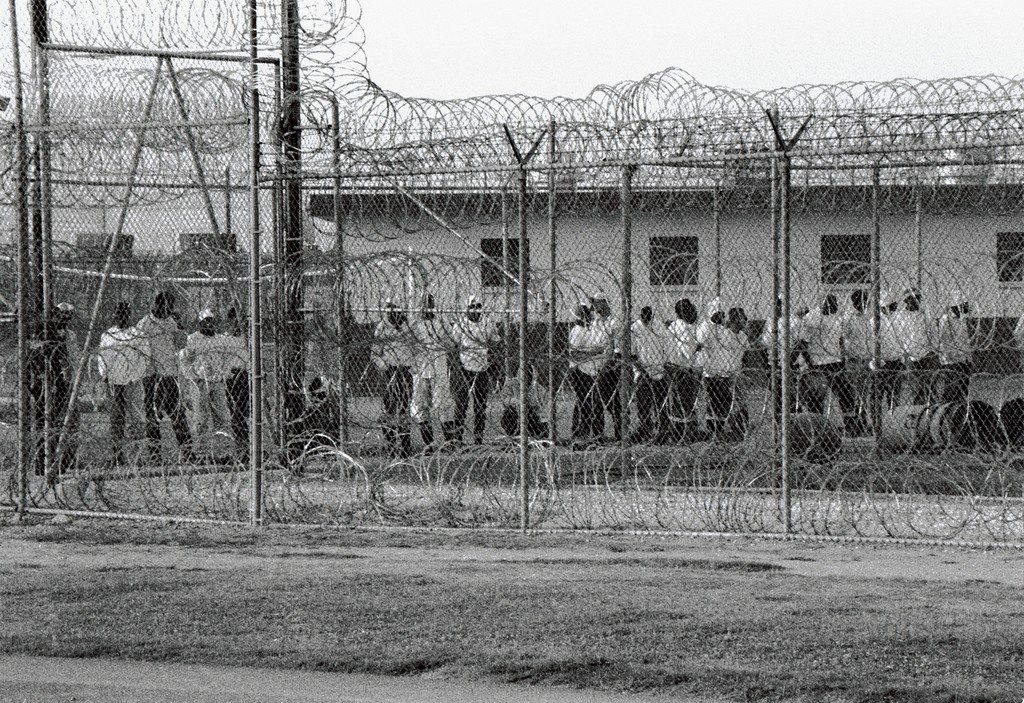

“Louisiana is the world’s prison capital. The state imprisons more of its people, per head, than any of its U.S. counterparts. First among Americans means first in the world. Louisiana’s incarceration rate is nearly five times Iran’s, 13 times China’s and 20 times Germany’s.” -Cindy Chang, The Times-Picayune

Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick have been documenting the African American community in New Orleans and its surrounding areas for the past three decades. Their work chronicles the unique traditions and deep-rooted elements of Louisiana culture that increasingly represent a vanishing way of life. Their photographs bear witness to both the celebrations and struggles of everyday life of docks workers along the Mississippi River sugar cane plantations on River Road, to laborers working sweet potato and cotton fields. While expository in nature, these works also celebrate the resilient community spirit that defines life in the region. Most recently, Keith and Chandra have produced an extensive body of work on Angola Prison, focusing on its incarcerated men and the impact of the prison system on their families. Angola, or its official name, The Louisiana State Penitentiary, also nicknamed the “Alcatraz of the South”, is the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. It is located on an 18,000-acre property that was previously the Angola and other plantations.

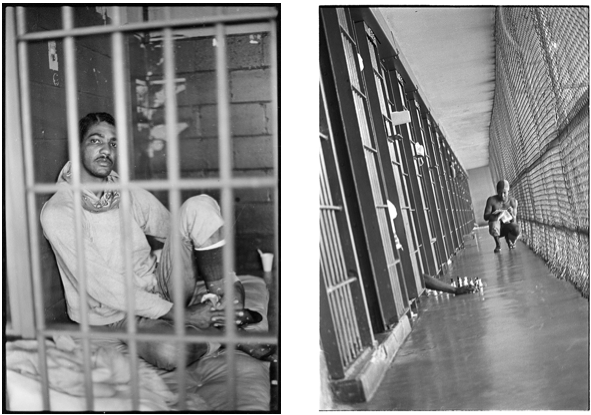

Keith Calhoun | (L)Glenn Demourelle, Angola State Prison CCR Lockdown, 1980. (R)23 Hour Lockdown, Chess Players, 1980. Archival pigment prints. Images courtesy of the artist.

Keith and Chandra: “We’re working on a body of photographs focused on the theme that prisons are slave plantations, especially Angola, It was transformed but it never really ended.”

Q: Is Angola a farm?

A: “No it’s a plantation. That’s the new revolutionized word, but we call it a plantation, not a farm. So we’re trying to have more than an art exhibit. Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate in the country. The schools are now incubators for prisons, we know that they’re the pipelines and kids in the city are prey. Now they don’t want kids to go into the French Quarter to play music, they have to have permits, and a lot of the things that kids once had have been eliminated, so what are you going to do? Are you going to send them to the streets? Here [at L9] this is an art center for the community. A lot of people here aren’t going to go to the CAC, they’re not going to go to Ogden, but they’ll come here. We have shows for the kids to get exposed to art, framing, and learning how to take a piece of work and turn it into something. But if they’re not exposed to that, it’s not likely that they’re going to walk into that situation. And art is classism, even in this city.”

Angola State Prison, Who’s that man on that horse, I don’t know his name, but they call him Boss, 1980. Archival pigment print. Image courtesy of the artist.

The work of Keith and Chandra has been exhibited at The Philadelphia African American Museum, Civil Rights Museum, New Orleans Museum of Art, The Smithsonian Institution, and Brooklyn Museum of Art. Keith is the recipient of The Press Club of New Orleans Award and The Michael P. Smith Memorial Award for Documentary Photography. His work has been included in several publications, including “Angola Bound,” Aperture, 2006; “Heroes of the Storm,” Aperture, 2010; and Deborah Willis’ Landmark Compilation Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photography 1840s to Present.

Chandra McCormick’s photograph Angola Rodeo Prison, Men Breaking Wild Horses depicts incarcerated men wrangling horses. For over 50 years, the annual Angola Prison Rodeo has taken place in a stadium near the prison. Prisoners compete in events such as bull riding and rope work. The rodeo is an ironic spectacle: the inmates are given opportunities to showcase skills, but the nature of the skillset —roping bulls or taming broncos — contrasts with the reality of the inmate’s lives behind bars. The rodeos allow the incarcerated to display artistic and athletic feats, but at the conclusion of the event they return to their cells. Angola, a nickname for the Louisiana State Penitentiary, is a maximum-security prison with a history fraught with racial tension, excessive periods in solitary confinement and policies that have prisoners laboring in fields, which some liken to slavery — a reality so divorced from the image of the iconic cowboy, empowered to freedom through riding horses.” — The Studio Museum in Harlem