Good Morning POU!

Today’s feature is a soldier that ordered his own death in order to defend this country.

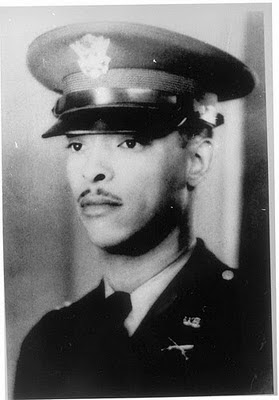

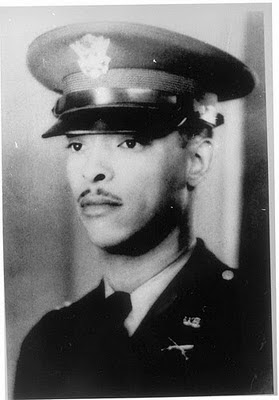

John R. Fox was born in Cincinnati, Ohio May 18, 1915, and attended Wilberforce University, graduating with an ROTC commission in 1940. He was 29 years old when he called artillery fire on his own position the day after Christmas in 1944, for which he was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1982. More than fifty years after his death, Fox was awarded the Medal of Honor. He is buried in Colebrook Cemetery in Whitman, Massachusetts.

The 92nd Infantry Division (colored), known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was a segregated division that fought in World War II. First Lieutenant John R. Fox was with the 366th Infantry Regiment’s 598th Field Artillery Battalion when he made the ultimate sacrifice in order to defeat the enemy and save the lives of his fellow soldiers.

When a massive German assault was launched on Sommocolonia, a windswept mountain village in the Serchio River Valley in the Apennine Mountains of northern Italy. in December 1944, a scant two platoons of American infantrymen were dug in here. Their own commanding officers expected them to throw down their guns and run. But for 20 critical hours, the tiny complement of 70 men, held out against an offensive that might have changed the course of World War II.

A mile to the north of Sommocolonia was the forward encampment of the German 14th Army, which had been instructed not to take prisoners from the 92nd Division because its soldiers were black – and, by official Nazi standards, not fully human.

Six miles to the south was the command post of the American Fifth Army, which refused to provide either reinforcements for the besieged troops in Sommocolonia or blood transfusions for their wounded. They were black, and by official U.S. Army standards in World War II, not fully soldiers. Fox was part of a small forward observer party that volunteered to stay behind in the village. From his position on the second floor of a house, Fox directed defensive artillery fire.

Shortly after midnight on December 26, 1944, Lt. Fox with ample time to withdraw prior to a German attack maintained his position on the second floor of a house directing defensive artillery fire until only a handful of defenders remained. The enemy was in the streets and attacking in strength, greatly outnumbering the small group of American soldiers. Fox radioed in to have the artillery fire adjusted closer to his position, then radioed again to have the shelling moved even closer.

As the Germans advanced, Fox spoke calmly by telephone to the Fire Direction Center, ordering up artillery missions from the distant guns. ‘That last round was just where I wanted it”, the young lieutenant reported. “Bring it in 60 yards more.”

The receiving operator thought Fox was mistaken – the order would train the full fire of up to 75 heavy caliber artillery guns directly on Fox’s position.

As a large number of Germans closed in, Fox indeed called for fire directly on the house. The soldier receiving the message was stunned, for that would bring the deadly fire right on top of Fox; there was no way he would survive. When Fox was told this, he replied, “Fire it! There’s more of them than there are of us.” The bombardment began. And within minutes, hundreds of shells had hit the target. each one powerful enough to blast the house and its occupants into oblivion. This shelling delayed the enemy advance until other units could reorganize to repel the attack.

When American troops retook the position, the bodies of Fox and others in his unit were found. The Army credited his actions with killing at least 100 Germans and delaying the attack until forces could be organized for a counterattack and regain control of the village.

Further insight into the events was later provided by the man on the other end of Fox’s radio.

Otis Zachary was the soldier receiving the message of John Fox, and was also one of Fox’s closest friends. They had trained together in Massachusetts in 1942 and shipped out on the same transport for Italy. An Artillery officer, Zachary understood that the targeting at Sommocolonia was Fox’s decision. Zachary had refused. to change the coordinates until he was ordered by a colonel to do what Lieutenant Fox asked.

Zachary, the soldier, fired on the position.

Zachary, the man, was tormented by the belief that that his shells had killed John Fox, his oldest friend in the Army. “When something like that happens, you go half nuts,” he told friends a half century later. “A lot of things still come back to me at night, so that I can’t sleep for thinking about them.”

Fox’s sacrifice was at first largely forgotten by the army, but in 1982 he was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. The award was presented at Fort Devens, Massachusetts by Major General James F, Hamlet, who also served in the 92nd during World War II. The citation presented tohis widow, the former Arlene Marrow of Brockton, Massachusetts, read in part as follows:

“Lieutenant Fox’s gallant and courageous actions, at the supreme sacrifice of his own life, greatly assisted in delaying the enemy advance until other infantry and artillery could reorganize to repel the attack…..His extraordinarily valorous actions were in keeping with the most cherished tradition of military service and reflect the utmost credit on him, his unit, and the U. S. Army.”

Later, he was finally awarded his Medal of Honor, along with several other black soldiers from WW2 who had been overlooked. Again, his widow received his award, from President Bill Clinton in a White House ceremony on January 13, 1997. His Medal of Honor Citation reads as follows:

For extraordinary heroism against an armed enemy in the vicinity of Sommocolonia, Italy on 26 December 1944, while serving as a member of Cannon Company, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Infantry Division. During the preceding few weeks, Lieutenant Fox served with the 598th Field Artillery Battalion as a forward observer. On Christmas night, enemy soldiers gradually infiltrated the town of Sommocolonia in civilian clothes, and by early morning the town was largely in hostile hands. Commencing with a heavy barrage of enemy artillery at 0400 hours on 26 December 1944, an organized attack by uniformed German units began. Being greatly outnumbered, most of the United States Infantry forces were forced to withdraw from the town, but Lieutenant Fox and some other members of his observer party voluntarily remained on the second floor of a house to direct defensive artillery fire. At 0800 hours, Lieutenant Fox reported that the Germans were in the streets and attacking in strength. He then called for defensive artillery fire to slow the enemy advance. As the Germans continued to press the attack towards the area that Lieutenant Fox occupied, he adjusted the artillery fire closer to his position. Finally he was warned that the next adjustment would bring the deadly artillery right on top of his position. After acknowledging the danger, Lieutenant Fox insisted that the last adjustment be fired as this was the only way to defeat the attacking soldiers. Later, when a counterattack retook the position from the Germans, Lieutenant Fox’s body was found with the bodies of approximately 100 German soldiers. Lieutenant Fox’s gallant and courageous actions, at the supreme sacrifice of his own life, contributed greatly to delaying the enemy advance until other infantry and artillery units could reorganize to repel the attack. His extraordinary valorous actions were in keeping with the most cherished traditions of military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him, his unit, and the United States Army.

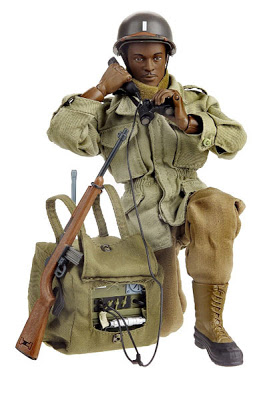

In 2006, Hasbro issued a limited edition John Fox action figure as part of their GI Joe series.