Good Morning POU!

Today’s post is a black history fact that I just learned about over the Easter weekend. A community easter egg hunt for children was being held at “the old Rosenwald school” in the county were I grew up in rural Alabama. I had no idea what that was and asked my Dad about it. That grew into an incredible conversation with my father and uncle educating me and my cousins. No one ever mentioned any such schools to us growing up. We never knew.

The Rosenwald Schools

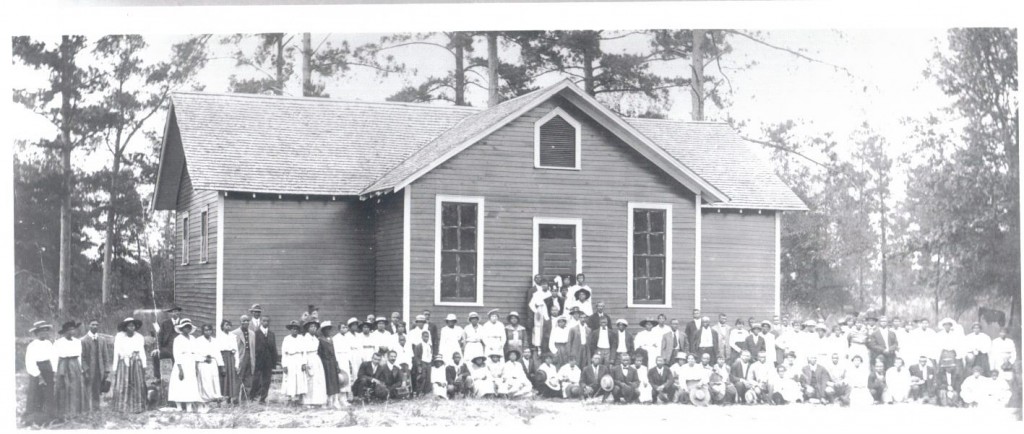

A Rosenwald School was the name informally applied to over five thousand schools, shops, and teachers’ homes in the United States which were built primarily for the education of African-Americans in the early 20th century. The need arose from the chronic underfunding of public education for African-American children in the South, who were required to attend segregated schools. Julius Rosenwald, an American clothier who became part-owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, was the founder of The Rosenwald Fund, through which he contributed seed money for many of the schools and other philanthropic causes.

To promote collaboration between white and black citizens, Rosenwald required communities to commit public funds to the schools, as well as to contribute additional cash donations. Millions of dollars were raised by African-American rural communities across the South to fund better education for their children.

Work-a-day African Americans enthusiastically embraced Rosenwald’s school construction plan — even though it meant considerable sacrifice on top of taxes they were already paying. Cash was scarce in this region where many people farmed “on shares.” To gather nickels and dimes, women of a community might hold a “box party,” fixing boxed lunches for neighbors to bid on. Families joined to plant an extra acre of cotton or raise hogs and chickens to be sold for the effort. Blacks who owned land might donate the school site, or cut trees to be sewn into boards for the work crews.

Despite Rosenwald’s matching donations toward the construction of black schools, by the mid-1930s, white schools in the South were worth, per student, over five times what black schools were worth per student (in majority-black Mississippi, this ratio was more than 13 to one).

The Plan

After the 1906 reorganization of the Sears company as a public stock corporation by the financial services firm of Goldman Sachs, one of the senior partners, Paul Sachs, often stayed with the Rosenwald family at their home during his many trips to Chicago. Julius Rosenwald and Sachs would often discuss America’s social situation, agreeing that the plight of African Americans was the most serious problem in the United States.

Sachs introduced Rosenwald to Booker T. Washington, the famed educator who in 1881 had been the first principal of the normal school which grew to become Tuskegee University in Alabama. Dr. Washington, who had gained the respect of many American leaders including U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, had also obtained financial support from wealthy philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie, George Eastman and Henry Huttleston Rogers. He encouraged Rosenwald, as he had others, to address the poor state of African-American education in the U.S.

The school building program was one of the largest programs administered by the Rosenwald Fund. Using state-of-the-art architectural plans designed by professors at Tuskegee Institute, the Fund spent more than four million dollars to build 4,977 schools, 217 teachers’ homes, and 163 shop buildings in 883 counties in 15 states, from Maryland to Texas. The Rosenwald Fund used a system of matching grants. Black communities raised more than $4.7 million to aid in construction . These schools became known as “Rosenwald Schools.” By 1932, the facilities could accommodate one- third of all African-American children in Southern schools. Research has found that the Rosenwald program accounts for a sizable portion of the educational gains of rural Southern blacks. This research also found significant effects on school attendance, literacy, years of schooling, cognitive test scores, and Northern migration, with gains highest in the most disadvantaged counties.

The Schools Impact on Communities

The Rosenwald Fund provided state-of-the-art architectural plans. Two black architecture professors at Tuskeegee, Robert R. Taylor and W.A. Hazel, drew the first set for a 1915 pamphlet The Negro Rural School and Its Relation to the Community. In 1920 Rosenwald official Samuel L. Smith assumed the task. His Community School Plans patternbooks were eventually distributed by the Interstate School Building Service and reached thousands of communities far beyond the South.

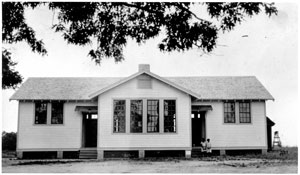

Rosenwald School |

Large banks of windows characterized Rosenwald Schools, a simple but powerful innovation in an era when electricity seldom reached into rural areas. Designers carefully specified room size and height, blackboard and desk placement, paint colors and even the arrangements of window shades in order to make best use of natural light. Marshaling the sun’s rays became almost an obsession for S.L. Smith. He insisted windows must be placed so that light came only from the students’ left, and he went so far as to provide different floorplans for schools depending upon which compass direction they faced.

Inside, the buildings almost always included meeting space, a key aspect of Booker T. Washington’s vision. In smaller buildings, a movable partition allowed classrooms to be thrown together as an assembly hall. Bigger schools featured a permanent auditorium. Dr. Washington saw each school as a community center. Rosenwald buildings would not only teach the young, but would help dispersed rural people come together to improve farming techniques and forge a strong community culture. Indeed families often built homes clustered around the schools, creating settlements that persist today.

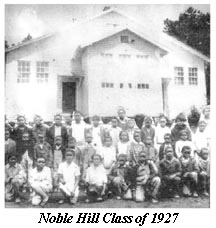

MARIAN COLEMAN REMEMBERS the Noble Hill School as just such a hub of African American life in Cassville, Georgia. “My dad said they were always having suppers and fundraisers, helping parents who couldn’t afford books for their children, or getting money for coal or wood to heat the school.” Village baseball teams competed on the grounds. “And any type of meeting they’d have to discuss the community, they’d use this building because it was big enough to hold the people.”

The wooden 1923 building looks modest by modern standards, but its two spacious high-ceilinged classrooms and third multi-purpose space made it far superior to the town’s previous black school, a one-room shanty condemned by the authorities.

“A man and his wife were the teachers” for many years, Coleman recalls. “The woman took the first through third graders in one room, the man over the older kids in the other, up to sixth grade.” An instructor’s work in those days did not stop when classes let out. “After school, youngsters knew not to get into fights on the way home – he’d pop out of nowhere to watch them and make sure they got home safe. Everyone in the community looked up to him to help raise the kids.” Indeed, teachers were expected to always be role models and leaders. “There wasn’t much in this town that the teachers were not a big part of.”

Unlike other endowed foundations, which were designed to fund themselves in perpetuity, The Rosenwald Fund was intended to use all of its funds for philanthropic purposes. Interestingly, in the Fund’s waning years after 1932, it ceased its construction grants and instead began giving scholarships to promising black thinkers. Ralph Ellison, to cite one famous example, wrote his searing book The Invisible Man on a Rosenwald Fellowship.

Preservation

In some communities, surviving structures have been preserved because of the deep meaning they had for African-Americans as symbols of their community dedication to education. In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Rosenwald Schools near the top of the country’s most endangered places and created a campaign to raise awareness and money for preservation. At least 23 former Rosenwald Schools are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

North Carolina ended up having the more Rosenwald schools than any other southern state. Though many of the schools have disappeared, there is one school still standing as the last Rosenwald school in Durham, NC.

Below is the story of The Russell Rosenwald School.