Good Morning POU!

The Gilded Age was a time of extreme wealth for a few, and extremely dire poverty for a whole lot more. Of course this era, the immediate years following reconstruction was of particular hardship for the vast majority of African-Americans, most of working age, were former slaves, with no more than the clothes on their backs as they trekked for better lives outside of the South, if they left at all. Jim Crow laws were put into effect, gains that were made, were snatched away by the fragility of the white ego.

Newport, Rhode Island has long been thought of as a playground for white socialites during the excessive Gilded Age — a Jay Gatsby world of railroad tycoons, summer parties and 70-room mansions. It is a city filled with over-the-top mansions. Cornelius Vanderbilt II, president and chairman of the New York Central Railroad, spared no expense when he built “The Breakers”. It has wall panels made of platinum.

But researchers have uncovered another side of the City by the Sea, a city embraced by black entrepreneurs, artists, free thinkers and even tourists from Philadelphia, Washington, New York and Boston.

“Newport was more than a summer colony for the Vanderbilts,” says Theresa Guzman Stokes, the author of a new website called “Gilded Age Newport in Color: The African American Summer Experience in Newport, Rhode Island, from 1870 to 1925.”

The Gilded Age is often tied to wealthy families such as the Astors, Belmonts and Berwinds. But blacks thrived during the period as well. Fleeing the rural South, they settled in Northern cities such as Newport. The new arrivals, along with the local descendants of New England slaves, found careers and developed a social, religious and intellectual center in 19th-century Newport, says Guzman Stokes.

Their impact was wide-ranging.

In 1842, George T. Downing started a catering business on Fourth and Broadway in NYC. His elaborate meals would soon make him the go to caterer for the wealthiest Americans. His work brought him in touch with many of the elites of the city, including the Astors, Kernochans, leRoys, Schermahorns, and Kennedys. His success allowed him to establish a summer business in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1849 he purchased the Bellevue Avenue estate in Newport from Charles Sherman.

In 1850 he moved to Providence, Rhode Island, continuing to work in Newport during the summer. In 1854 he built the Sea Girt Hotel, which was burnt to the ground on December 15, 1860 by an arsonist. (sure, guess why) He replaced the building with Downing Block, part of which he rented to the Government to serve as a Naval Academy hospital. In 1865 he moved to Washington, D.C. with the encouragement of representative Nathan F. Dixon II where he conducted the House Refectory for twelve years. In 1877 he moved back to Newport, where he retired in 1880.

From: Opening the Oyster George T. Downing and African American Catering in Rhode Island

By the mid 19th century, successful African American catering establishments under the ownership of Isaac Rice, Steven Payne, D. B. Allen and Jacob Dorsey indulged a burgeoning vacationing class of New York scions and swells who would eventually line Bellevue Avenue with gilded summer cottages.

Joining these ranks and soon surpassing his competition was one George T. Downing of New York City. Following the example of his celebrated father, Thomas, whose lavish Wall Street oyster house served up pickled oysters and boned and jellied turkeys to Charles Dickens, Queen Victoria and Gotham gentry for two generations, George opened his own restaurant in New York in 1842 at 3 Broad St. And in 1846, at age 27, lured by New York’s “famous 400”—Astors, Kings and Wetmores among them—during their watering season in Newport, he opened what some referred to as a branch of his father’s oyster house.

Not yet considered a delicacy, oysters were abundant, sloppy and dished out in seedy dens. Downing the elder brought respectability to New York’s ubiquitous oyster cellars with a conspicuous consumption that drew the upper crust. Decorating with mirrors, damask, gilt and chandeliers, Downing created a place that women could attend without shame.

George Downing wrote of his father’s plump, prized oysters, “Ladies and gentlemen with towels in hand, and an English oyster knife made for the purpose, would open their own oysters, drop into the burning hot concaved shell a lump of sweet butter and other seasoning and partake of a treat. Yes, there was a taste imparted by the saline and lime substance in which the juice of the oyster reached boiling heat that made it a delicate morsel.”

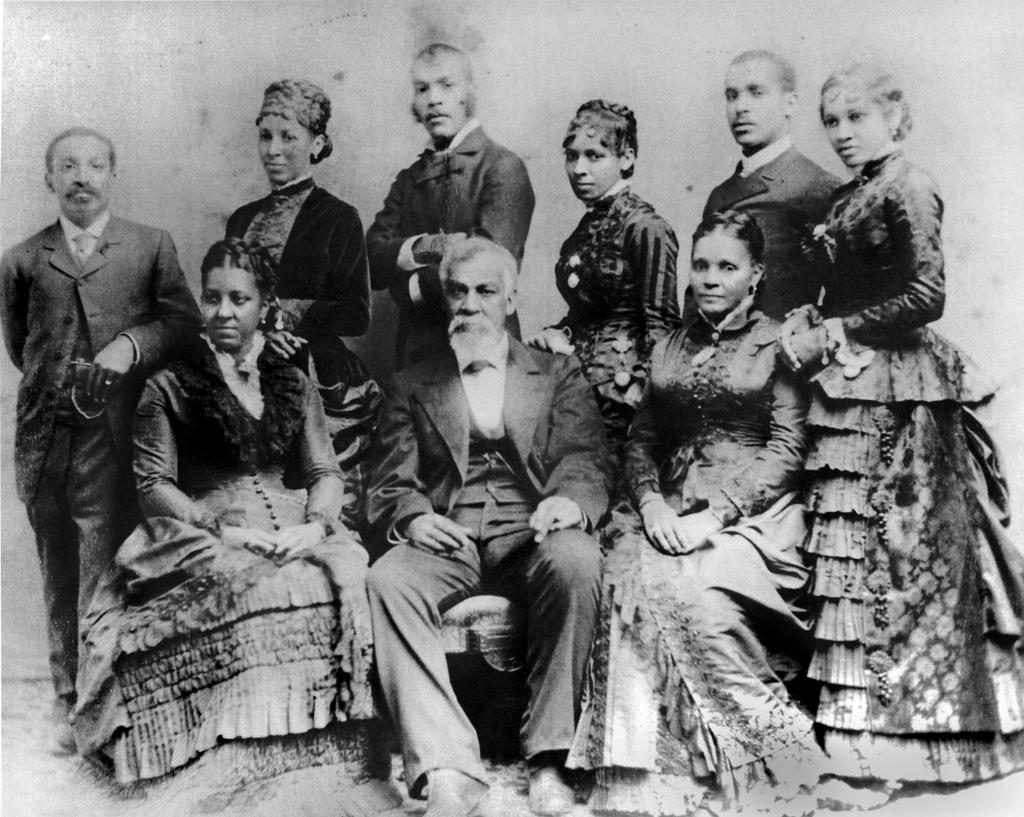

Pictured above is the family of Rev. Henry Jeter. Jeter was the pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church for 42 years. Jeter also became a prominent leader in the national Baptist church and African American civil rights organizations. He was a founding member of the New England Baptist Convention. He was also a member of the National Afro-American League. In 1903 he attended the National Baptist convention in Philadelphia. He was also active in the Republican Party, participating in city Republican Convention in 1903.

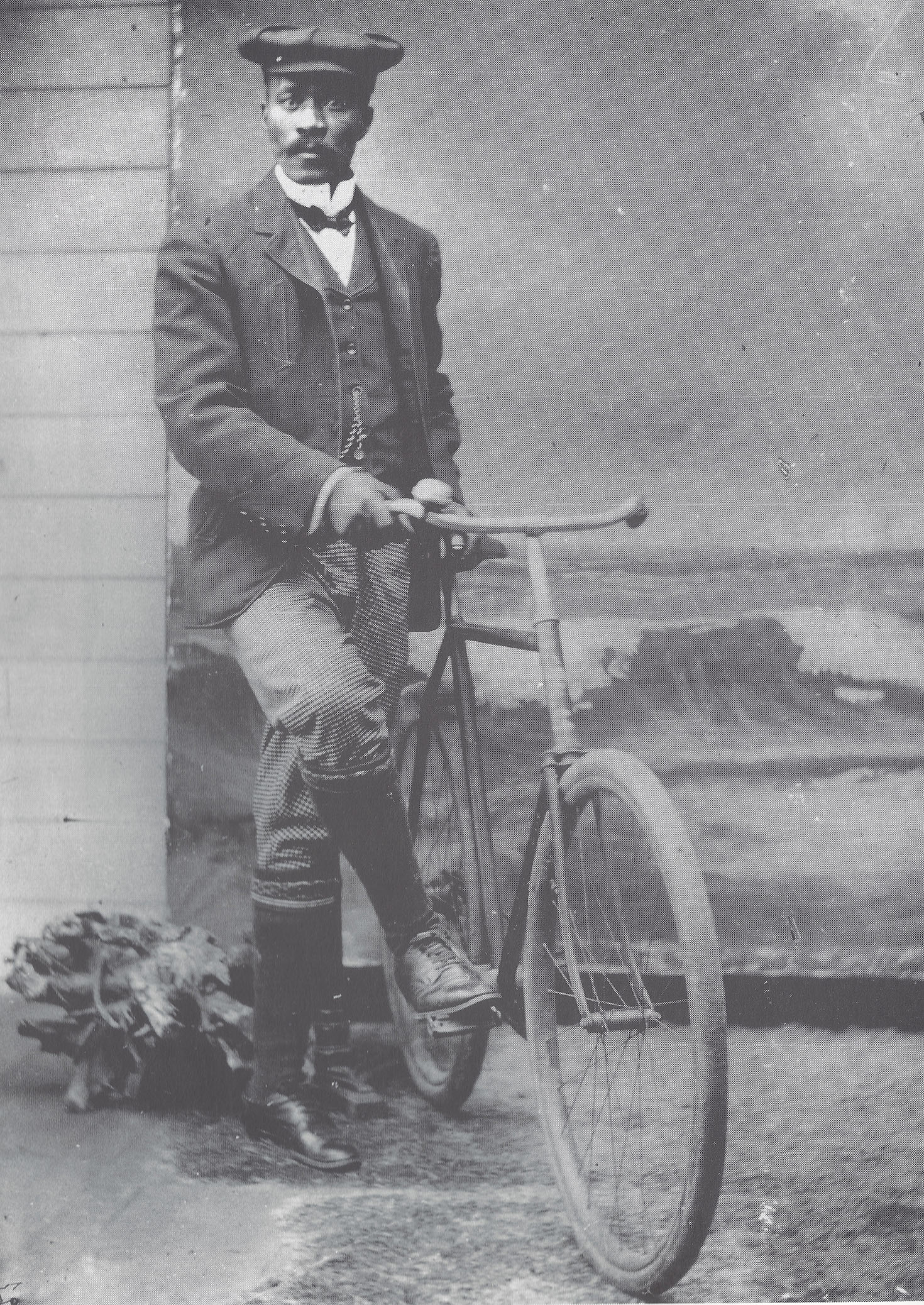

Newport’s first black doctor, Marcus Wheatland, was the first in the city to use an X-ray machine to diagnose his mostly white patients. Mary Dickerson, a “fashionable” dressmaker, was a founding member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. And Armstead Hurley, originally from Virginia, ran a painting business and helped start the Rhode Island Loan & Investment Co., the state’s, as well as one of the country’s, first black-owned bank. Dr. Alonzo Van Horne (pictured below), son of Rev. Mahlon Van Horne, graduated from Howard Medical School in 1897 and became the first African American dentist in Newport.

Their stories appear on www.gildedageincolor.com, a website created by the 1696 Heritage Group, a Newport company founded by Theresa Guzman Stokes and her husband, Keith Stokes. A Rhode Island Council for the Humanities grant helped pay for the research.

The old photographs, drawn from the Newport Historical Society and the Stokes Family Collection, provide a rare look at the lives of Newport’s black residents and visitors, Guzman Stokes says. “People are used to seeing southern, plantation-style sharecroppers on their front porches. They don’t expect to see women in Victorian dress or families going to the beach.”

By the end of the 19th century, Newport was an internationally celebrated vacation spot and leading summer colonies for many of the country’s wealthiest families. During that same era, professional class families of color were also enjoying the social and economic benefits of Newport. At that time, Newport would boast a sizable population of middle and professional class African Americans, and during the summer months, families of color from New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., would come to Newport to socialize and take part in all of the recreational activities “America’s First Resort” had to offer. The Colored Washington Newspaper in 1886 described a Newport summer experience, reporting, “If there was a watering place in America where respectable, refined and well-bearing colored ladies and gentlemen have as little reason to feel their color as in Newport.”

While blacks and others lived in segregated communities elsewhere, blacks in Newport lived on Historic Hill and The Point, often next to whites and close to their jobs or place of worship, she says. They joined black social clubs and fraternal organizations, including Odd Fellows, Boyer Lodge, Knights of Pythias and Queen Ester Lodge #11.

The Gilded Age occurred around the same time as the nation’s Jim Crow laws and lynchings in the South, says Keith Stokes, who is an historian. Blacks weren’t looking for integration, but as American citizens they wanted equal access to housing, jobs, education and public office. Newport was a rare community where blacks were free to live, work, worship “and assemble for their own self-interests.”