Good Morning POU!

Today we feature another genius Lighting Designer, creating those incredible moments on Broadway, behind the scenes.

Some of the finest performances being given on the states of America, and across the world are the creations of the unseen artists. They are invisible to us physically, but their work is vibrant and alive. Williams H. Grant III, is a native New Yorker, and of the most creative and successful theatrical lighting designers on today’s contemporary scene of dance, opera and drama.

Grant attended school in the city, and went on to the Hartt College of Music in Connecticut to study the flute and harp and was interested in a career in classical music. A chance meeting between Grant and the technical director of the theatre at Hartt College inspired the young flutist to learn the rudiments of designing a plan for theatrical lighting, and with the director’s help, Grant began to learn what was now to become his profession. “I know that I wanted that kind of power,” Grant says of the ability to make a stage come alive or appear happy or sad merely by lighting and changing the moods.

Grant initially moved to Los Angeles to become a studio musician, but he was given the chance to be a technical director with the Aspen Music Festival and began sending our resumes for lighting director opportunities. As luck would have it, C. Bernard Jackson of the Inner City Cultural Center in Los Angeles hired Grant as technical director of its theatres.

What is not known by many people are the intricacies of lighting design and that the designer should have skills in electrical systems, how to operate a light board, manipulate a dimmer system, and have a keen sense of the color spectrum much like a painter of canvases. The light plot is, according to Grant, “a blueprint of the design. The exact hanging location of every instrument is plotted so the electrician see’s where to hang each instrument.”

“In addition are hook-up sheets detailing the design of the lights and their focus, and the cue sheets which instruct when to implement the designer’s ideas in accordance with the action, actor’s line or the progression of the performance.”

Grant is the author of A Basic Handbook of Stage Lighting, which was published in 1981. It is described by Grant as being “a concise and practical approach to design that could fit in the technician’s backpocket as he hung lights.”

Grant says the most important purpose is to allow the actors, props and setting to be seen. Lighting must make a statement, a definition of time and space. Lighting must create the appropriate environment, a picture in which the actor appears in proper relationship to his surroundings.”

Though there remains a small percentage of blacks in the lighting industry, Grant is pleased that his inspiration came from one of the first black women in the lighting union, Shirley Prendergast, who he worked as an assistant to a number of shows. Grant was taken under Prendergast’s wing and learned more about the art; he also was honored to have her write the introduction to his handbook. He in return is acting as mentor to a young woman of color coming up in the field, Cassandra Scott.

Grant believes more blacks should investigate the technical side of theatre and become the geniuses behind the scenes. “The financial benefits are quite attractive as well.”

Grant has designed lighting for dance, opera and theater all over the world. In the US, he’s designed for the Alliance Theatre Company, North Shore Music Theatre, The Cleveland Playhouse, and The Alabama Shakespeare Festival.

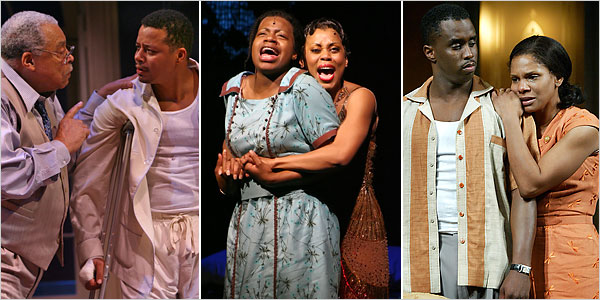

His designs have appeared at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and on Broadway including the notable all-African American production of Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, directed by Debbie Allen and starring Terrence Howard, Phylicia Rashad, James Earl Jones, and Anika Noni Rose.

He’s designed for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and The American Ballet Theater, and was resident lighting designer for The Philadelphia Dance Company (Philadanco) for 28 years.

He is the recipient of the 2007 Suzi Bass Award for Outstanding Lighting Design for Elliot, a Soldier’s Fugue.

Theatergoers witnessing William Grant’s work are assured everytime, that when the lights go up on the stage, the master-impressionist is in the house.