GOOD MORNING P.O.U.!

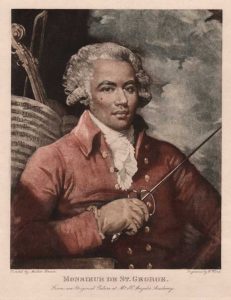

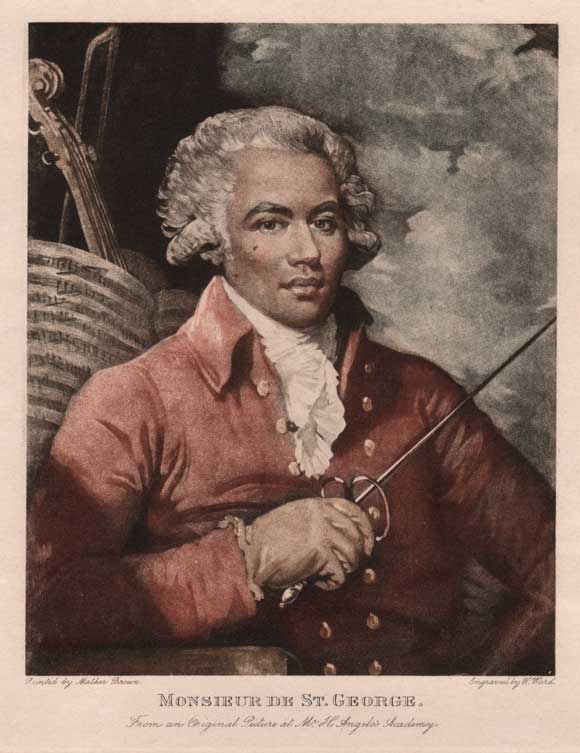

JOSEPH BOLOGNE, CHEVALIER DE SAINT-GEORGES

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (December 25, 1745 – June 10, 1799)[1] was a champion fencer, a virtuoso violinist and conductor of the leading symphony orchestra in Paris. Born in Guadeloupe, he was the son of George Bologne de Saint-Georges, a wealthy planter, and Nanon, his African slave.[2] During the French Revolution, Saint-Georges was colonel of the Légion St.-Georges,[3] the first all-black regiment in Europe, fighting on the side of the Republic. Today the Chevalier de Saint-Georges is best remembered as the first classical composer of African ancestry.

Youth and education

Born in Baillif, Basse-Terre, he was the son of George Bologne de Saint-Georges, a wealthy planter on the island of Guadeloupe, and Nanon, his African slave.[4] His father, called “de Saint-Georges” after one of his plantations in Guadeloupe, was a commoner until 1757, when he acquired the title of Gentilhomme ordinaire de la chambre du roi (Gentleman of the king’s chamber).[5] Misled by Roger de Beauvoir’s 1840 romantic novel Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges,[6] most of his biographers confused Joseph’s father with Guillaume-Pierre de Boullogne, Controller of Finance, whose family was ennobled in the 15th century. This led to the erroneous spelling of Saint-Georges’ family name as “Boulogne”, persisting to this day, even in the BnF, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In 1753, his father took Joseph, aged seven, to France for his education.[7] Two years later, on August 26, 1755, listed as passengers on the ship L’Aimable Rose, Bologne de Saint-Georges and Negresse Nanon landed in Bordeaux.[8] In Paris, reunited with their son Joseph, they moved into a spacious apartment at 49 rue Saint André de Arts.

Joseph was 13 when he was enrolled in Tessier de La Boëssière’s Académie royale polytechnique des armes et de ‘l’équitation (fencing and horsemanship). According to La Boëssière fils, son of the Master: “At 15 his [Saint-Georges’] progress was so rapid, that he was already beating the best swordsmen, and at 17 he developed the greatest speed imaginable.”[9] He was still a student when he beat Alexandre Picard, a fencing-master inRouen, who had been mocking him as “Boëssière’s mulatto”, in public. That match, bet on heavily by a public divided into partisans and opponents of slavery, was an important coup for the latter. His father, proud of his feat, rewarded Joseph with a handsome horse and buggy.[10] In 1766 on graduating from the Academy, Joseph was made a Gendarme du roi (officer of the king’s bodyguard) and a chevalier.[11] Henceforth Joseph Bologne, by adopting the suffix of his father, would be known as the “Chevalier de Saint-Georges”.

In 1764 when, at the end of the Seven Years’ War George Bologne returned to Guadeloupe to look after his plantations, he left Joseph an annuity of 8000 francs and an adequate pension to Nanon who remained with her son in Paris.[12] According to his friend, Louise Fusil: “… admired for his fencing and riding prowess, he served as a model to young sportsmen … who formed a court around him.”[13] A fine dancer, Saint-Georges was also invited to balls and welcomed in the salons (and boudoirs) of highborn ladies. “Partial for the music of liaisons where amour had real meaning… he loved and was loved.”[14] Yet he continued to fence daily in the various salles of Paris. It was there he met the Angelos, father and son, fencing masters from London, the mysterious Chevalier d’Éon, and the teenage Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, all of whom would play a role in his future.

Music

Nothing is known about Saint-Georges’s early musical training. “Platon”, a fictional whip-toting slave commander on Saint-Domingue who, in Beauvoir’s novel “taught little Saint-Georges” the violin, is a figment of the author’s imagination.[15] Given his prodigious technique as an adult, Saint-Georges must have practised the violin seriously as a child. Yet, not before 1764, when violinist Antonio Lolli composed two concertos for him,[16] and 1766, when François Gossec dedicated a set of six Trios to Saint Georges, was it revealed that the famous swordsman also played the violin. The dedications also suggest that Lolli polished his violin technique and Gossec was his composition teacher. There is no basis to the not always reliable François-Joseph Fétis’ claim that Saint-Georges studied violin withJean-Marie Leclair, however similar traits in technique indicate Pierre Gaviniès as one of his mentors.

In 1769, the Parisian public was amazed to see Saint-Georges, the great fencer, among the violins of Gossec’s new orchestra,Le Concert des Amateurs. Two years later he became its concertmaster, and in 1772 he created a sensation with his debut as a soloist, playing his first two violin concertos, Op. II, with Gossec conducting the orchestra. “These concertos were performed last winter at a concert of the Amateurs by the author himself, who received great applause as much for their performance as for their composition.”[17] According to another source, “The celebrated Saint-Georges, mulatto fencer [and] violinist, created a sensation in Paris … [when] two years later … at the Concert Spirituel, he was appreciated not as much for his compositions as for his performances, enrapturing especially the feminine members of his audience.”[18]

Saint-Georges’ first compositions, Op. I, were a set of six string Quartets, among the first in France. They were inspired by Haydn’s earliest quartets imported from Vienna by the eccentric Baron Bagge,[19] whose musicales were frequented by some of the best musicians in Paris, including Joseph. Two more sets of six string quartets, three charmingforte-piano and violin sonatas, a sonata for harp and flute and six violin duos make up his chamber music output. A cello sonata performed in Lille in 1792, a concerto for clarinet and one for bassoon were lost. Twelve additional violin concertos, two symphonies and eightsymphonie-concertantes, a new, intrinsically Parisian genre of which Saint-Georges was one of the chief exponents complete the list of his instrumental works, published between 1771 and 1779, a short span of eight years. Six opéra comiques and a number of songs in manuscript complete the list of his works, remarkable considering his many extra-musical activities.

In 1773, when Gossec took over the direction of the prestigious but troubled Concert Spirituel, he designated Saint-Georges as his successor as director of theConcert des Amateurs. Less than two years under his direction, “Performing with great precision and delicate nuances [the Amateurs] became the best orchestra for symphonies in Paris, and perhaps in all of Europe.”[20] As the Queen attended some of Saint-Georges’ concerts at the Palais de Soubise, arriving sometimes without notice, the orchestra wore court attire for all its performances. “Dressed in rich velvet or damask with gold or silver braid and fine lace on their cuffs and collars and with their parade swords and plumed hats placed next to them on their benches, the combined effect was as pleasing to the eye as it was flattering to the ear.”[21] Saint-Georges played all his violin concertos as soloist with his orchestra. Their corner movements are replete with daring batteriesand bariolages,[22] brilliant technical effects made possible by the new bow designed by Nicholas Pierre Tourte Père – a perfect foil in the hands of a great swordsman. While their fast movements reveal the composer probing the outer limits of his instrument, his slow movements are lyrical and expressive, with an occasional touch of Creole nostalgia.

Saint-Georges was fortunate to be already established as a professional musician, because in 1774, when his father died in Guadeloupe, his annuity was awarded to his legitimate half-sister, Elisabeth Benedictine.[23] While before that he contributed his services to theAmateurs, he now asked for and was willingly granted a generous fee by the sponsors of the orchestra, which he had turned into the largest and most prestigious ensemble in Europe.

In 1776 the Académie royale de musique, the (Paris Opéra), was once again in dire straits. Saint Georges was proposed as the next director of the opera. As creator of the first disciplined French orchestra since Lully, he was the obvious choice to rescue the prestige of that troubled institution. However, alarmed by his reputation as a taskmaster, three of its leading ladies “… presented a placet (petition) to the Queen [Marie Antoinette] assuring her Majesty that their honor and delicate conscience could never allow them to submit to the orders of a mulatto.”[24] To keep the affair from embarrassing the queen, Saint-Georges promptly withdrew his name from the proposal. Meanwhile, to defuse the brewing scandal, Louis XVI took the Opéra back from the city of Paris – ceded to it by Louis XIV a century ago – to be managed by his Intendant of Light Entertainments. Following the “affair,” Marie-Antoinette preferred to hold her musicales in the salon of her petit appartement de la reine in Versailles. The audience was limited to her intimate circle and only a few musicians, among them the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. “Invited to play music with the queen,”[25] Saint-Georges probably played his violin sonatas, with her Majesty playing the forte-piano.

The placet also ended forever Saint-Georges’ aspirations to the highest position of any musician in Paris. It was, as far we know, the most serious setback he suffered due to his color. Compared to the upheavals to come, it was a tempest in a teapot, but the wound it inflicted on Saint-Georges would fester until the Revolution. Over the next two years he published two more violin concertos and a pair of his Symphonies concertantes. Thereafter, despite of his humiliation by the operatic divas, except for his final set of quartets (Op. 14, 1785), Saint-Georges, fascinated by the stage, abandoned composing instrumental music in favor of opera.

(CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE)