Opera

Ernestine, Saint-Georges’s first opera, with a libretto by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, future author of Les Liaisons dangereuses, was performed on July 19, 1777 at the Comédie-Italienne. It did not survive its premiere. The critics liked the music, but panned the weak libretto, given precedence over the music at the time.[26] The Queen was there with her entourage. She came to support Saint-Georges’s opera but, after the audience kept echoing a character cracking his whip and crying “Ohé, Ohé,” the Queen gave it the coup de grace by calling to her driver: “to Versailles, Ohé!”[27]

Thanks to that fiasco, the Marquise de Montesson, morganatic wife of the Duke of Orléans, realized her ambition to engage Saint-Georges as music director of her fashionable private theater. As the failure of Ernestine had left Saint Georges insolvent, he was glad that his new position also entitled him to an apartment in the ducal mansion on the Chaussée d’Antin. After his mother died in Paris, Mozart stayed there with Melchior Grimm, who, as personal secretary of the Duke, lived in the mansion. The fact that Mozart spent over two months under the same roof with Saint-Georges, confirms that they knew each other.[30] As an added incentive, the duke appointed Saint-Georges Lieutenant de la chasse of his vast hunting grounds at Raincy, with an additional salary of 2000 Livres a year. “Saint-Georges the mulatto so strong, so adroit, was one of the hunters…”[31] Saint-Georges wrote and rehearsed his second opera, appropriately named La Chasse at Raincy. At its premiere in the Théâtre Italien, “The public received the work with loud applause. Vastly superior compared with ‘Ernestine’ … there is every reason to encourage him to continue [writing operas].”[32]La chasse was repeated at her Majesty’s request at the royal chateau at Marly.[33] Saint-Georges’ most successful opéra comique was L’Amant anonyme, with a libretto based on a play by Mme de Genlis.[34] As a close friend of Saint-Georges, couldFélicité Genlis’ anonymous hero, who woos his adored from afar but dares not to allow her to see his face, have been modeled on Saint-Georges, a ‘mulatto,’ able to be loved but never married by European women?[35]

In 1781, due to the massive financial losses incurred by its patrons in shipping arms to the American Revolution,[36] Saint Georges’s Concert des Amateurs had to be disbanded. Not one to let it go without a fight, Saint-Georges turned to his friend and admirer, Philippe D’Orléans, duc de Chartres, for help. In 1773 at age 26, Philippe was elected Grand Master of the ‘Grand Orient de France’ after uniting all the Masonic organizations in France. Responding to Saint-Georges’s plea, Philippe revived the orchestra as part of the Loge Olympique, an exclusive Freemason Lodge. Renamed Le Concert Olympique, with practically the same personnel, it performed in the grand salon of the Palais Royal. In 1785, Count D’Ogny, grandmaster of the Lodge and member of its cello section, authorized Saint-Georges to commission Haydn to compose six new symphonies for the “Concert Olympique.” Conducted by Saint-Georges, Haydn’s “Paris” symphonies were first performed at the Salle des Gardes-Suisses of the Tuileries, a much larger hall, in order to accommodate the huge public demand to hear Haydn’s new works.

In 1785, the Duke of Orléans died. The Marquise de Montesson, his morganatic wife, having been forbidden by the king to mourn him, shuttered their mansion, closed her theater, and retired to a convent near Paris. With his patrons gone, Saint-Georges lost not only his positions, but also his apartment. Once again it was his friend, Philippe, now Duke of Orléans, who presented him with a small flat in the Palais Royal. Living in the Palais, Saint-Georges was inevitably drawn into the whirlpool of political activity around Philippe, the new leader of the Orléanist party, the main opposition to the absolute monarchy. As a strong Anglophile, Philippe, who visited England frequently, formed a close friendship with George, Prince of Wales. Due to the recurring mental illness of King George III, the prince was expected soon to become Regent. While Philippe admired Britain’s parliamentary system, Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville, his chief of staff, envisioned France as a constitutional monarchy, on the way towards a republic. With Philippe as France’s “Lieutenant-general” he promoted him as the sole alternative to a bloody revolution.

Meanwhile the duke’s ambitious plans for re-constructing the Palais-Royal left the Orchestre Olympique without a home and Saint-Georges unemployed. Seeing his protégé at loose ends and recalling that the Prince of Wales often expressed a wish to meet the legendary fencer, Philippe approved Brissot’s plan to dispatch Saint-Georges to London to ensure the Regent-in-waiting’s support of Philippe as future “Regent” of France. But Brissot had a secret agenda as well. He considered Saint-Georges, a “man of color,” the ideal person to contact his fellow abolitionists in London and ask their advice about his plans for Les Amis des Noirs (Friends of the Blacks) modeled on the English anti-slavery movement.[37]

London and Lille

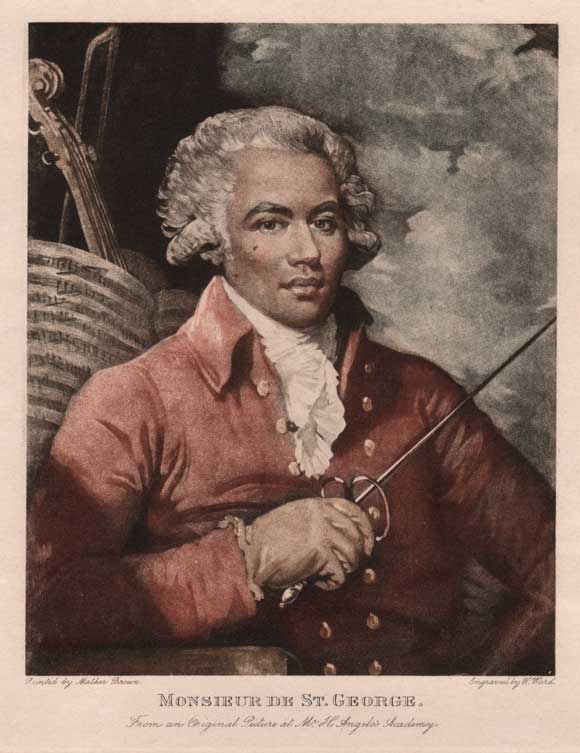

In London, Saint-Georges stayed with fencing masters Domenico Angelo and Henry, his son, whom he knew as an apprentice from the halls of arms of Paris. They arranged exhibition matches for him including one at Carlton House, before the Prince of Wales, who received Saint-Georges graciously.[38] After sparring with him, carteand tierce,[39] the prince matched him with several renowned masters, including the mysterious transvestite, La Chevalière D’Éon, aged 59, in a voluminous black dress[40] A painting by Charles Jean Robineau[41] showing the Prince and his entourage watching “Mlle” D’Éon score a hit on Saint-Georges gave rise to rumors that he allowed it out of gallantry for a lady.[42] But, as Saint-Georges knew “her” having fenced with dragoon Captain D’Eon in Paris, it was probably in deference to D’Eon’s age. And, though Saint-Georges spent the rest of his stay entertaining his exigent friend, the Prince, he still took time to play one of his concertos at the Anacreontic Society.[43] He also delivered Brissot’s request to the abolitionists MPs William Wilberforce, John Wilkes, and the Reverend Thomas Clarkson. Before Saint-Georges left England, Prinny, as his intimates called him, presented him with a brace of pistols, so true as to kill at 30 yards’ distance. Prinny also had him sit for his portrait.[44] Asked by Mrs Angelo if it was a true likeness, Saint-Georges replied, “Alas, Madame it is frightfully so.”[45]

Back in Paris, he completed and produced his latest opéra comique, La Fille Garçon, also at the Théâtre des Italiens. Once again the critics found the “poem” wanting. (Could it be that since operas were sung in French the weakness of their librettos became more evident?) “The piece, [was] sustained only by the music of Monsieur de Saint Georges…. The success he obtained should serve as encouragement to continue enriching this theatre with his productions.”[46]

Compared with London, Saint-Georges found Paris seething with pre-revolutionary fervor. It was less than a year before the great conflagration. Meanwhile, with the re-construction of the Palais nearly finished, Philippe had opened several new theaters. The smallest of them was the Théâtre Beaujolais, a marionette theater for children, named after his youngest son, the duc de Beaujolais. The lead singers of the Opéra provided the voices for the puppets. It is for them Saint-Georges wrote the music of Le Marchand de Marrons (The Chestnut Vendor) with a libretto by Mme. De Genlis, Philippe’s former mistress and then confidential adviser.

While Saint-Georges was away, the Concert Olympique had resumed performing at theHôtel de Soubise, the old hall of the Amateurs, but with a different conductor: the Italian violinist Jean-Baptiste Viotti.[47] Disenchanted, Saint-George, together with the talented young singer Louise Fusil, and his friend, the horn virtuoso Lamothe, embarked on a brief concert tour in the North of France. On May 5, 1789, the opening day of the fateful Estates General, Saint-Georges, seated in the gallery with Laclos, heard Jacques Necker[48] raising his feeble voice to state, “The slave trade is a barbarous practice and must be eliminated.”Choderlos de Laclos, who replaced Brissot as Philippe’s chief of staff, intensified Brissot’s campaign promoting Philippe as an alternative to the monarchy. Concerned by its success, Louis dispatched Philippe on a bogus mission to London. On July 14, 1789, the fall of the Bastille, King Louis XVI missed his opportunity to govern, and Philippe, Duke of Orléans, missed his chance to save the monarchy.

Saint-Georges, sent ahead by Laclos, stayed at Grenier’s; this hotel in Jermyn Street was a place for those bent on extravagance[49] and it was patronised by French refugees. Saint-Georges was entertaining himself lavishly.[50] His salaries gone, his largesse had to come from Philippe. Once again his assignment was to stay close to the Prince of Wales. It was not a difficult task. As soon as he arrived, Prinny took Saint-Georges to his fabled Marine Pavilion in Brighton, where he won bets placed on his guest’s prowess, took him fox hunting and to the races at Newmarket. But when Philippe arrived, it was he who became Prinny’s regular companion. Saint-Georges was rather relieved at not having to cater to Prinny’s extravagant caprices, like making him jump through a speeding carriage or vault Richmond Castle’s moat (presumably on horseback), to keep Philippe in the prince’s thoughts.[51] Incidentally, while either Philippe or Saint-Georges were often seen with the Prince of Wales, it was never both at the same time.

(CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE)