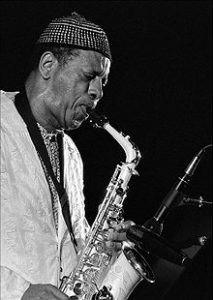

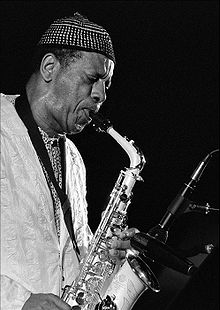

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman was an American jazz saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter, and composer. In the 1960s, he was one of the founders of free jazz, a term he invented for his album Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation. His “Broadway Blues” has become a standard and has been cited as an important work in free jazz. His album Sound Grammar received the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for music.

Coleman was born in 1930 in Fort Worth, Texas, where he was raised. His sister, Truvenza Coleman claims that he was born on March 9, 1931. He attended I.M. Terrell High School, where he participated in band until he was dismissed for improvising during “The Washington Post” march. He began performing R&B and bebop on tenor saxophone and started The Jam Jivers with Prince Lasha and Charles Moffett. Eager to leave town, he accepted a job in 1949 with a Silas Green from New Orleans traveling show and then with touring rhythm and blues shows. After a show in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, he was assaulted and his saxophone was destroyed. He switched to alto saxophone, which remained his primary instrument, first playing it in New Orleans after the Baton Rouge incident. He then joined the band of Pee Wee Crayton and traveled with them to Los Angeles. He worked at various jobs, including as an elevator operator, while pursuing his music career.

In California he found like-minded musicians such as Ed Blackwell, Bobby Bradford, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, and Charles Moffett. He recorded his debut album, Something Else!!!! (1958) with Cherry, Higgins, Walter Norris, and Don Payne. During the same year he belonged briefly to a quintet led by Paul Bley that performed at a club in New York City. By the time Tomorrow Is the Question! was recorded soon after with Cherry, Higgins, and Haden, the jazz world had been shaken up by Coleman’s alien music. Some jazz musicians called him a fraud, while conductor Leonard Bernstein praised him.

In 1959 Atlantic released The Shape of Jazz to Come According to music critic Steve Huey, the album “was a watershed event in the genesis of avant-garde jazz, profoundly steering its future course and throwing down a gauntlet that some still haven’t come to grips with.” Jazzwise listed it No. 3 on their list of the 100 best jazz albums of all time.

Coleman’s quartet received a lengthy – and sometimes controversial – engagement at New York City’s famed Five Spot jazz club. Such notable figures as the Modern Jazz Quartet, Leonard Bernstein and Lionel Hampton were favorably impressed, and offered encouragement. (Hampton was so impressed he reportedly asked to perform with the quartet; Bernstein later helped Haden obtain a composition grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.) Opinion was, however, divided. Trumpeter Miles Davis famously declared Coleman was “all screwed up inside”, although Davis recanted this comment and became a proponent of Coleman’s innovations.

Coleman’s unique early sound was due in part to his use of a plastic saxophone. He had first bought a plastic horn in Los Angeles in 1954 because he was unable to afford a metal saxophone, though he didn’t like the sound of the plastic instrument at first. Coleman later claimed that it sounded drier, without the pinging sound of metal. In later years, he played a metal saxophone.

On the Atlantic recordings, Coleman’s sidemen in the quartet are Cherry on cornet or pocket trumpet, Haden, Scott LaFaro, and then Jimmy Garrison on bass, and Higgins or his replacement Ed Blackwell on drums. The complete released recordings for the label were collected on the box set Beauty Is a Rare Thing.

In 1960, Coleman recorded Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, which featured a double quartet, including Don Cherry and Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet, Haden and LaFaro on bass, and both Higgins and Blackwell on drums. The record was recorded in stereo, with a reed/brass/bass/drums quartet isolated in each stereo channel. Free Jazz was, at nearly 40 minutes, the lengthiest recorded continuous jazz performance to date, and was instantly one of Coleman’s most controversial albums. The music features a regular but complex pulse, one drummer playing “straight” while the other played double-time; the thematic material is a series of brief, dissonant fanfares. As is conventional in jazz, there are a series of solo features for each member of the band, but the other soloists are free to chime in as they wish, producing some extraordinary passages of collective improvisation by the full octet. In the January 18, 1962 issue of Down Beat magazine, in a special review titled “Double View of a Double Quartet,” Pete Welding awarded the album Five Stars while John A. Tynan rated it No Stars.

Coleman intended “free jazz” as simply an album title, but his growing reputation placed him at the forefront of jazz innovation, and free jazz was soon considered a new genre, though Coleman has expressed discomfort with the term. Among the reasons Coleman may not have entirely approved of the term ‘free jazz’ is that his music contains a considerable amount of composition. His melodic material, although skeletal, strongly recalls the melodies that Charlie Parker wrote over standard harmonies, and in general the music is closer to the bebop that came before it than is sometimes popularly imagined. Coleman very rarely played standards, concentrating on his own compositions, of which there seemed to be an endless flow. There are exceptions, though, including a classic reading (virtually a recomposition) of “Embraceable You” for Atlantic, and an improvisation on Thelonious Monk’s buy viagra finland “Criss-Cross” recorded with Gunther Schuller.

After the Atlantic period and into the early part of the 1970s, Coleman’s music became more angular and engaged fully with the jazz avant-garde which had developed in part around his innovations.

His quartet dissolved, and Coleman formed a new trio with David Izenzon on bass, and Charles Moffett on drums. Coleman began to extend the sound-range of his music, introducing accompanying string players (though far from the territory of Charlie Parker with Strings) and playing trumpet and violin (which he played left-handed) himself. He initially had little conventional musical technique and used the instruments to make large, unrestrained gestures. His friendship with Albert Ayler influenced his development on trumpet and violin. Haden would later sometimes join this trio to form a two-bass quartet.

Between 1965 and 1967 Coleman signed with Blue Note Records and released a number of recordings starting with the influential recordings of the trio At the Golden Circle Stockholm. In 1966, Coleman recorded The Empty Foxhole, with a trio featuring Haden and Coleman’s son Denardo Coleman – who was ten years old. While some, like Shelly Manne and Freddie Hubbard, regarded this as perhaps an ill-advised piece of publicity on Coleman’s part and judged the move a mistake. Denardo became his father’s primary drummer in the late 1970s.

Coleman formed another quartet. Haden, Garrison, and Elvin Jones appeared, and Dewey Redman joined the group, usually on tenor saxophone. On February 29, 1968 in a group with Haden, Ed Blackwell, and David Izenzon Coleman performed live with Yoko Ono at Albert Hall. One song was included on the album Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band (1970) He continued to explore his interest in string textures – from Town Hall, 1962, culminating with the Skies of America album in 1972.

Coleman, like Miles Davis before him, took to playing with electrified instruments. The 1976 funk album Dancing in Your Head, Coleman’s first recording with the group which later became known as Prime Time, prominently featured electric guitars. While this marked a stylistic departure for Coleman, the music maintained certain similarities to his earlier work. These performances had the same angular melodies and simultaneous group improvisations – what Joe Zawinul referred to as “nobody solos, everybody solos” and what Coleman called harmolodics – and although the nature of the pulse was altered, Coleman’s rhythmic approach did not.