Early black militants were as militant as Malcolm X.

Because African-American patriots were more successful at achieving their political agenda for black people, the voices of uncompromising 19th century militants have largely been relegated to the dustbin of history, making Malcolm X. appear to be a historical anomaly. But long before him, there were black political figures and activists who spoke vociferously against America and its founding fathers.

When a speaker at a meeting of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society referred to Thomas Jefferson as “a good anti-slavery man,” he was interrupted by shouts: “He sold his own daughter!” Robert Purvis, a wealthy octoroon who was born free, asked for the floor and condemned Jefferson and Washington, saying: “Sir, Thomas Jefferson was a slaveholder and I hold all slaveholders to be tyrants and robbers. It is said that Thomas Jefferson sold his own daughter. This if true proves him to have been a scoundrel as well as a tyrant!”

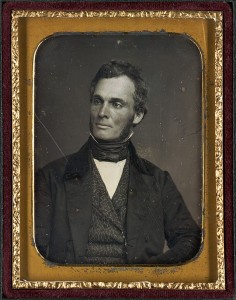

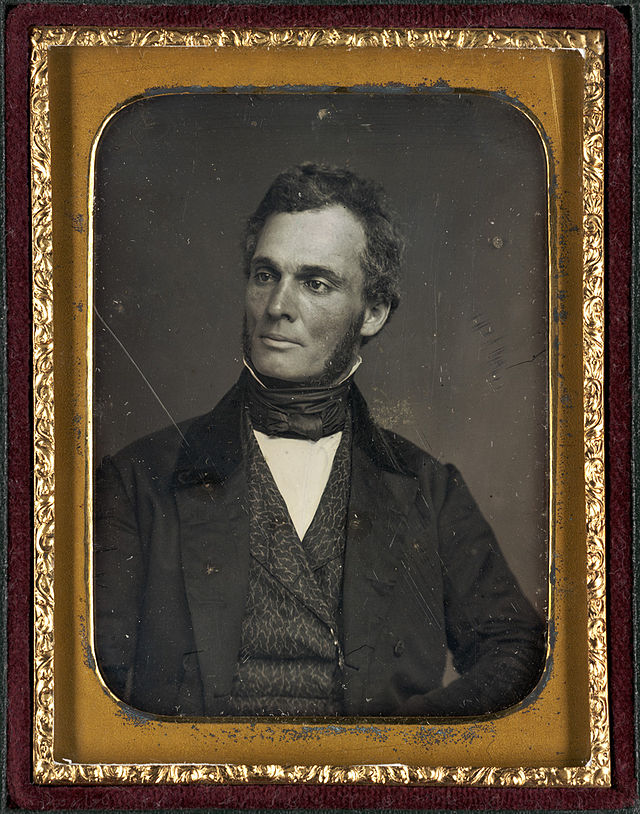

Robert Purvis (August 4, 1810 – April 15, 1898) was an African-American abolitionist in the United States. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, educated at Amherst College in Massachusetts, and lived most of his life in Philadelphia. In 1833 he helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society there and the Library Company of Colored People. From 1845-1850 he served as president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and also traveled to England to gain support for the movement.

Of mixed race, Purvis and his brothers were three-quarters European by ancestry and inherited considerable wealth from their native English father after his death in 1826. Their parents had lived in common-law marriage, prevented from marrying because their mother was a free woman of color, of African and Jewish descent. The sons chose to identify with the black community and used their education and wealth to support abolition of slavery and anti-slavery activities, as well as projects in education to help the advance of African Americans.

Purvis was born in 1810 in Charleston, South Carolina. His mother, Harriet Judah, was a free woman of color, the daughter of former slave Dido Badaraka and Baron Judah, a Jewish American born in Charleston. Robert’s father was William Purvis, an English immigrant. As an adult, Purvis told about a reporter about his family: he said that his maternal grandmother Badaraka had been kidnapped at age 12 from Morocco, transported to the colonies on a slave ship, and sold as a slave in Charleston. He described her as a full-blooded Moor: dark-skinned with tightly curled hair. She was freed at age 19 by her master’s will. Harriet’s father was Baron Judah, of European Jewish descent. Also Born in Charleston, Baron was the third of ten children of Hillel Judah, a German Jewish immigrant, and Abigail Seixas, his Sephardic Jewish wife, who was born in Charleston.

Purvis told the reporter that his grandparents Badaraka and Judah had married. His 21st-century biographer thought that unlikely, given the social prominence of the Judah family in Charleston. She learned that Judah’s parents had owned slaves. Badaraka and Judah had a relationship for several years, and Harriet and a son were their children together. In 1790 Judah broke off his relationship with Badaraka when he moved with his parents from Charleston to Savannah, Georgia. In 1791 he moved to Richmond, Virginia. There he married a Jewish woman and had four children with her.

William Purvis was from Northumberland; he had immigrated to the United States as a young man with some of his brothers to make their fortunes. He became a wealthy cotton broker in Charleston and a naturalized US citizen. After their father died when they were children, their mother had moved the family to Edinburgh, Scotland for her sons’ education.

William Purvis and the younger Harriet Judah lived together as husband and wife, but racial law prevented their marriage. The couple had three sons: William born in 1806, Robert born in 1810, and Joseph born in 1812. In 1819 Purvis moved all the family north to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where the boys attended the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society’s Clarkson School. Purvis intended to consolidate his business affairs and return with his family to England, where he thought his sons would have better opportunities. He died in 1826 before they could move.

In 1833, Purvis helped abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison establish the American Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia and signed its “Declaration of Sentiments”. Living for nearly the rest of the 19th century, Purvis was the last surviving member of the society. Also in 1833, Purvis helped establish the Library Company of Colored People, modeled after the Library Company of Philadelphia, a subscription organization. With Garrison’s support, Purvis traveled to England to meet leading abolitionists.

In 1838, he drafted the “Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens Threatened with Disfranchisement”‘, which urged the repeal of a new state constitutional amendment disfranchising free African Americans. There were widespread tensions and fears among whites following Nat Turner’s slave rebellion of 1831 in Virginia. Although Pennsylvania was a free state that had abolished slavery, state legislators persisted in passing this amendment to restrict free blacks’ political rights. They did not regain suffrage until after the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, following the Civil War.

According to his records, Purvis estimated that from 1831 until 1861, he helped one slave per day achieve freedom, aiding a total of more than 9,000 slaves to escape to the North. He used his own house, located outside the city, as a station on the Underground Railroad.

Purvis supported many progressive causes in addition to abolition. With his good friend Lucretia Mott, he supported women’s rights and suffrage. He believed in integrated groups working for greater progress for all. By the end of the Civil War, which gained the emancipation of slaves and suffrage for black men, Purvis had reached his late 50’s and became less active in political affairs.

n 1832, Purvis married Harriet Davy Forten, a woman of color and daughter of wealthy sailmaker James Forten and his wife Charlotte, both prominent abolitionists and leaders in Philadelphia. Like her parents and siblings, Harriet Forten Purvis was active in anti-slavery groups in the city, including the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.

The Purvises had eight children, including son Charles Burleigh Purvis (1841-1926). He became a surgeon and professor for 30 years in the medical school at Howard University. In addition, the couple raised Harriet’s niece, Charlotte Forten Grimké, after her mother died. After Harriet died, Purvis married Tacy Townsend, who was of European descent. As a public figure, he received some criticism for this marriage, from both whites and blacks who cared about the color line.

Charles Lenox Remond expressed his opposition to America more broadly. An eyewitness observer said that after Dred Scott v. Sanford, Remond delivered an address calling for swift, decisive action: “He boldly proclaimed himself a traitor to the government and the Union, so long as his rights were denied. Were there a thunderbolt of God which he could invoke to bring destruction upon this nation, he would gladly do it.