Graphic Design is a subset of the Industrial Design family. Also known as communication design, it is the art and practice of planning and projecting ideas and experiences with visual and textual content. The form of the communication can be physical or virtual, and may include images, words, or graphic forms. The experience can take place in an instant or over a long period of time.

The work can happen at any scale, from the design of a single postage stamp to a national postal signage system, or from a company’s digital avatar to the sprawling and interlinked digital and physical content of an international newspaper. It can also be for any purpose, whether commercial, educational, cultural, or political.

A graphic designer may use a combination of typography, visual arts, and page layout techniques to produce a final result. Graphic design often refers to both the process (designing) by which the communication is created and the products (designs) which are generated.

Today we feature a pioneer in the field of Graphic Design, and also a sure movie in the making!

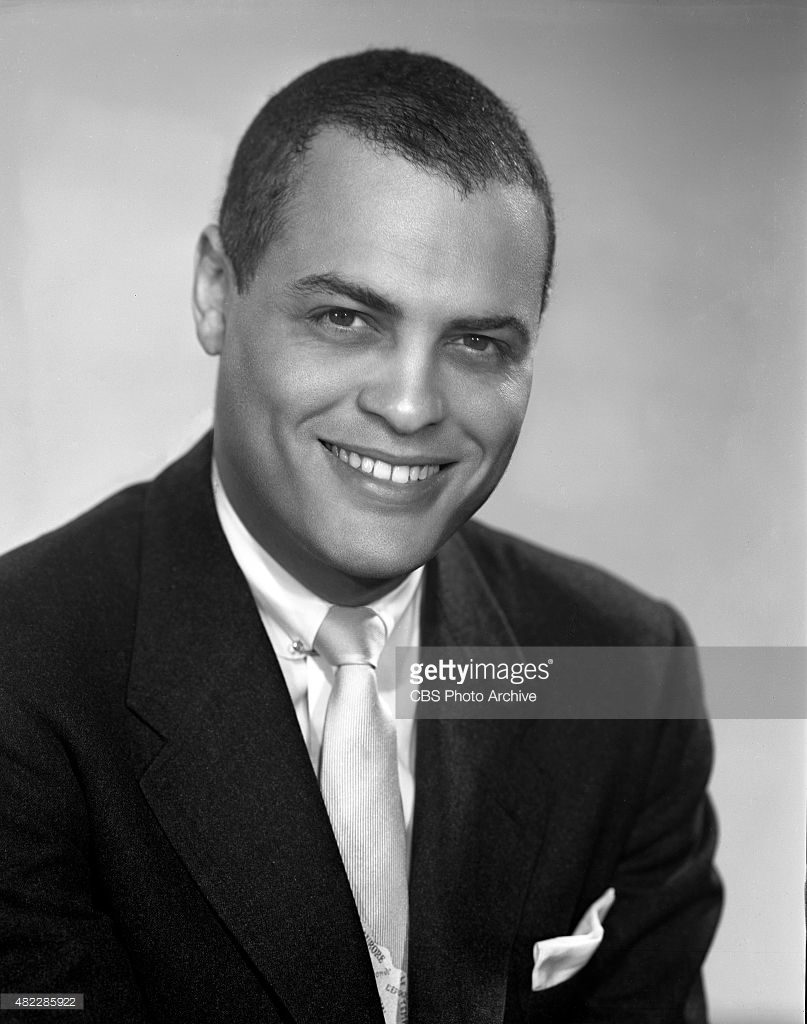

He was born George Elliott Olden Birmingham, Alabama, the grandson of a slave and the son of a Baptist minister. His father had escaped slavery and fought in a black regiment of the Union Army during the Civil War. Olden’s mother, a New Orleans beauty from whom he apparently inherited his much admired looks, was a classically trained singer. In youth he attended Dunbar High School in Washington, DC., then Virginia State College, before dropping out shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor to work as a graphic designer for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner of the CIA.

When the war ended in 1945, his supervisor in the OSS, Colonel Lawrence W. Lowman, who in civilian life became Vice President of CBS’s television division, recommended him to the agency’s Director of Communications. From a one-man operation involved with six programs a week, Olden eventually headed a staff of 14 in charge of 60 weekly shows. When he joined the network in 1945, there were 16,000 television sets in the entire nation. By the time he left the network in 1960, there were 85 million sets, one for every two Americans.

In 1945, before Jackie Robinson played Major League baseball, or Marian Anderson sang at the Metropolitan Opera, Georg Olden, the grandson of a slave, took a job with CBS. From 1945 to 1960, Olden worked with William Golden, art director for CBS, and as such was one of the first African-Americans to work in television.

There, as head of the network’s division of on-air promotions at the dawn of television, Olden pioneered the field of broadcast graphics. Working under CBS’s art director, William Golden, he supervised the identities of programs such as I Love Lucy, Lassie and Gunsmoke; helped produce the vote-tallying scoreboard for the first televised presidential election returns (the 1952 race between Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai E. Stevenson); and collaborated with esteemed artists and designers, including David Stone Martin, Ed Benguiat, Alex Steinweiss and Bob Gill.

Speculation remains whether it was Olden or William Golden, who designed the Eye logo for the network in 1951. Given CBS’s normal operations, which set Olden in charge of the design for all on-air promotional images, it makes sense that he would have had a hand in the Eye’s development. Further, Golden never explicitly said on-record that he created the logo, rather that it evolved when CBS decided to make its radio and television divisions distinct. The Eye was born to mark the television side, which points to Olden’s credit.

Soon after joining CBS, Olden was also invited to attend the San Francisco conference that eventually led to the formation of the United Nations. He was named the official graphic designer for what would be the U.N. International Secretariat. Olden was selected for the post by Edward R. Stettinius, the U.S. Secretary of State at that time.

In 1960, he began to work in advertising and went on to design the Clio Award as well as receive seven of them.

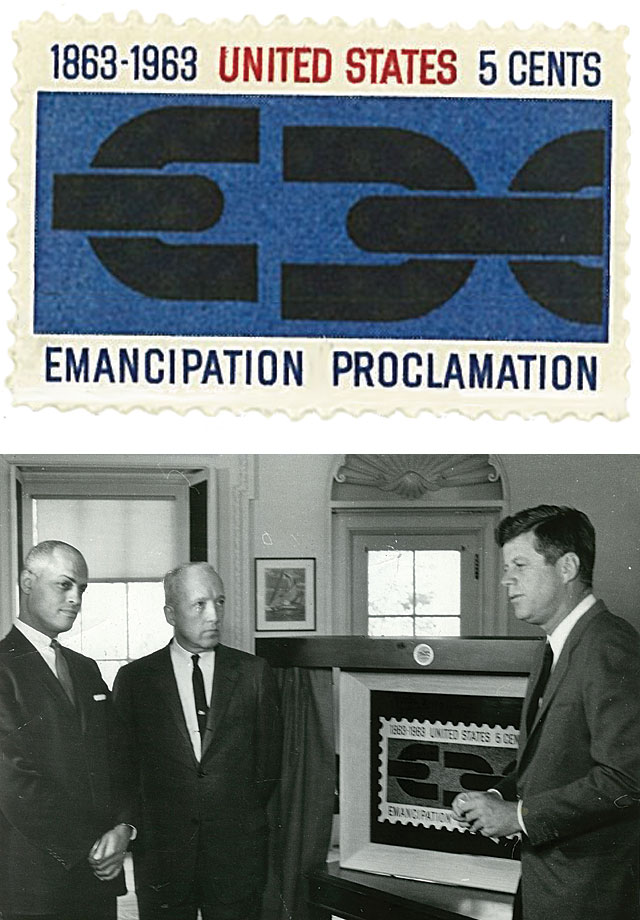

Olden might have rested comfortably at CBS, but he soldiered on in corporate America, surmounting obstacles that barred many other people of color from advancement, despite the efforts of the civil rights movement. In 1960, he took a job as television group art director at the advertising agency BBDO. Ebony magazine photographed him in his windowed office on Madison Avenue and described him admiringly as “an artist, a dreamer, a designer, a thinker and a huckster.” In 1963, he joined an elite department within the ad agency McCann-Erickson. That year, he became the first African American to design a postage stamp—a broken chain commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. At a White House ceremony with Olden in attendance, President John F. Kennedy praised the stamp as “a reminder of the extraordinary actions in the past as well as the business of the future.”

He has been said to have a mixed legacy in terms of race. Ebony magazine profiled him several times in the 1950s and ’60s as one who had grasped the opportunities offered by a new communications medium and risen to an executive rank. But it was far from easy. In 1954, Ebony reported that of the 72,400 people employed full-time in television, fewer than 200 were black. The jobs included “print-machine operator” and “wardrobe mistress.” “Acceptance is a matter of talent,” Olden told the magazine in 1963. “In my work I’ve never felt like a Negro. Maybe I’ve been lucky.”

He tended to avoid pressing racial issues or pressing firms to hire blacks, but in 1970, he sued his former employer, McCann Erickson, for wrongful termination caused by discrimination. The case failed.

Olden v. McCann Erickson

Olden’s life took a hairpin turn to demise when he was laid off from McCann-Erickson in August of 1970. Olden had long argued in his career that race was not a contributing factor to his early success. Devastated and furious, Olden could only make sense of the situation if he attributed blame to racial discrimination, clearly a pervasive and pressing problem in the United States, but not one that had had an effect on Olden’s professional journey before. The reason given to Olden was economic—a recession—but Olden, who had not experienced a day’s unemployment in 25 years was devastated by what he clearly saw as betrayal.” He had been lucky in his career, yet he had also clearly been a talented designer. Affidavits stated that McCann recognized Olden as “a superb talent in contemporary graphics and art direction.” Believing that McCann was racially motivated in moving him out of the company in order to impede his moving up to senior executive status, Olden filed a racial discrimination lawsuit with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the New York State Division of Human Rights. Because 20 other professionals had been laid off at the same time, all of whom, other than Olden, were white, the EEOC and Division of Human Rights found no discriminatory practices at McCann. Olden would not accept the findings and sought representation from the Center for Constitutional Rights, which filed a class-action suit against McCann in U.S. District Court.

In 1966, Olden divorced Courtenaye MacBeth, his wife of 25 years and married singer Terri Phillips Baker. However the decline of his career after the failed lawsuit, caused his estrangement from his second wife. Olden was becoming largely forgotten by his contemporaries and began to become bitter “over his dismissal from the advertising industry and loss of stature. In 1972 Olden left New York to move to Southern California, reportedly to start his own company.

Olden than began living with his 28-year-old, German-born girlfriend, Irene Mikolajczyk, known as Maya.

On January 25, 1975, only days before the class-action lawsuit filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights was to go to trial, Olden was fatally shot with a .357 Magnum by Maya. She pled not guilty and was released on $1,000 bail. She was acquitted on May 14, 1975.

In a posthumous edition of Who’s Who, he supplied his own unconscious epitaph: “As the first black American to achieve an executive position with a major corporation, my goal was the same as that of Jackie Robinson in baseball: to achieve maximum respect and recognition by my peers, the industry and the public, thereby hopefully expanding acceptance of, and opportunities for, future black Americans in business.”

Watch his appearance on the CBS show “I’ve Got A Secret” in 1963.